'X' is for X-Ray

Written by Morgen Mills, former Program Coordinator at the Labrador Institute

X is always a tricky letter, but in Labrador, “x-ray” is no mere topic of alphabetical convenience! As one of the Labrador Institute’s Heritage Minutes explored back in 2016, the x-ray ships of the Grenfell Mission are an important part of our twentieth-century history.

The Grenfell Mission was a maritime undertaking from its very beginnings, having first arisen out of the National Mission to Deep Sea Fishermen in 1892, after Wilfred Grenfell spent a season travelling the Labrador coast aboard the mission’s medical ship Albert. He soon afterwards founded his own branch of the mission in order to expand its medical services on the Labrador coast, with the result that he and other mission personnel continued to ply the coast for decades, aboard various vessels. Every visit to an isolated community served to extend the network of medical service, and to forward the mission's colonial objectives in all areas of local society, such as education, industry, and religion.

Still, visits by ship are by nature temporary, and the mission’s continuous Labrador presence and infrastructure were soon necessarily based on shore. A hospital was built at Battle Harbour in 1893, and others followed. As the mission expanded, these permanent locations provided more effective bases of operation than ships, as well as greater in-patient capacity and the ability to operate year-round.

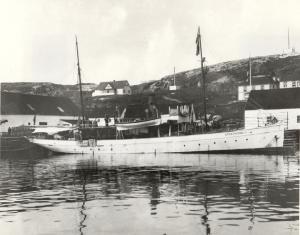

The Labrador coastline is long, however, and the population was even more widely distributed a century ago than it is today. Even with the hospitals and clinics, there remained a clear demand for mobile medical service; this demand led Grenfell to launch the mission’s first large, well-equipped hospital ship, the Strathcona, in 1899. At the time it was absolutely cutting-edge, offering one of the world's first sea-going x-ray clinics, and it became something of a flagship for the mission, serving not only to provide medical service in Labrador, but also to represent the ethos and character of the mission itself, both internally and abroad. The ship was named for major donor Lord Strathcona, who had himself been a Hudson’s Bay Company trader at Rigolet and North West River early in his career, before he became one of Canada’s most prominent businessmen (today he is commemorated by Strathcona House in Rigolet).

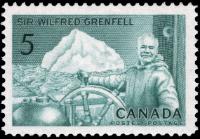

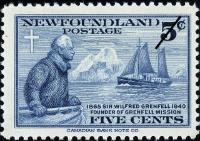

Grenfell loved to strike a gallant pose at the Strathcona’s helm or in its bow, and he was depicted just so in promotional portraits for fundraising (and later, on postage stamps).

Sir Wilfred Grenfell has been featured on both Canadian and Newfoundland stamps.

The image of the intrepid, seafaring missionary doctor was central to the Grenfell Mission’s core narrative, and it fit in well with the missionary principles that Grenfell espoused. As a non-denominational perspective on religion and charity, so-called “muscular Christianity” emphasized manliness, daring, and patriotism in service. This movement was also closely associated with British imperialism, and Grenfell’s many ideas for social reform certainly belonged to the larger colonial project of the British Empire. Even so, his vision of the adventuring missionary doctor was widely taken up by the North American popular imagination as well, and helped him to realize extraordinary successes in securing funds for the mission’s works.

For many years Grenfell undertook extensive lecture tours, and he wrote tirelessly about his own experiences and ideas of medical mission service. As a part of this strategy, he even popularized tales of autobiographical adventure on the sea, such as the story of his having been “adrift on an icepan.” Many contemporary romantic novels took up these themes in fiction as well, including several set in Labrador and clearly based on Grenfell himself, such as Norman Duncan’s Doctor Luke of the Labrador.

Still, far beyond its symbolic value, the Strathcona also offered extreme utility, carrying its onboard x-ray equipment, dispensary, and sick beds up and down the coast at a time when local community healthcare facilities were minimal. All of this took place prior to the public funding of healthcare and when governmental services to Labrador of any sort were virtually non-existent, so that in spite of all the larger mission’s complex and often problematic legacies, the Strathcona ships clearly enabled the provision of a humanitarian service of indisputable value.

Arguably even more important than the first Strathcona were the mission’s later x-ray ships, including the Strathcona II and especially the Strathcona III.

Strathcona I, c1910, as published in Grenfell's Labrador: The Country and the People, from the Heritage NL website

Strathcona II at Battle Harbour, Donald and Miriam MacMillan collection, Peary-PacMillan Arctic Museum.

Strathcona III, 1966 or 1967. Photo by Christopher Wynes, Labrador Institute Archive.

Grenfell and his Labrador-based lieutenant, Dr. Harry Paddon, each often wrote that improvements in Labradorians’ health depended upon improvements in their education and material circumstances. Within the realm of medicine, however, they identified two clear, leading culprits of disease. These were malnutrition and tuberculosis. Many factors contributed to malnutrition, and diverse means were employed to address the problem, by many agencies, including the Grenfell Mission. Tuberculosis, on the other hand, as serious and pernicious a problem as it was, was also exactly the sort of medical challenge that lay squarely within the mission’s primary focus area.

The mitigation of Labrador’s recurring tuberculosis epidemics was not swift or, arguably, ever fully completed, and the problems certainly persisted long after the days of Grenfell and Paddon. Indeed, limited outbreaks still occur in Labrador today. Nonetheless, the Grenfell Mission did achieve notable successes in dramatically reducing levels of active disease and the suffering it caused.

Chest x-rays are a key technique in diagnosing pulmonary tuberculosis, which is the active form of the disease in a patient’s lungs. The Strathcona ships could carry x-ray equipment directly into small harbours along the coast, allowing diagnostic x-rays to be taken where that would otherwise have been impossible. The Strathcona III, built in 1966, was especially well-equipped for this work. It possessed modern navigational equipment and other design features specifically intended to allow the ship to travel through narrow fjords and tickles that were often full of shoals.

A chest x-ray taken by Dr. Christopher Wynes at the Nain nursing station during a tuberculosis outbreak in the winter of 1966-1967, showing active disease in the right lung. Wynes served as Assistant Medical Officer in North West River under Dr. Tony Paddon from July 1966-December 1967, and he travelled all over Labrador by float plane, ship, and snowmobile. During one trip to Nain, Wynes x-rayed 60 patients, using the potato store as a darkroom, since it was the darkest room in the clinic. Photo from the Labrador Institute Collection.

Another of Wynes’s photos, showing the Strathcona III against the Torngat Mountains.

The campaign against tuberculosis had complex impacts, and medical officials often did not fully understand or respect Indigenous agency, causing social damage in communities across the North—for example, through the removal of patients to distant sanatoria. At the same time, the benefits of mobile diagnostic capability were tremendous from a public health perspective. For example, in 1970 the Strathcona III was able to support a mass tuberculosis survey in northern Labrador—as described in some detail online by historian John Matchim. Similar work was done throughout Newfoundland as well, including famously by the Christmas Seal x-ray ship, and there were also railway- and bus-based travelling x-ray clinics, specially designed to fight tuberculosis in rural and outport Newfoundland. Heritage NL has an article devoted to the topic, by Keith Collier.

X-rays were also used for other purposes, and indeed the x-ray ships were used for far more than just x-rays. Dental service and tooth extractions must have been particularly welcome! But the Strathcona ships are remembered today especially for being among the first ships in the world to carry onboard x-ray equipment to sea, and for their innovation in healthcare delivery and combating tuberculosis later in the 20th century.