'C' is for Capelin

Written by Chelsea Boaler, former Research Associate, Labrador Institute.

On a leap of faith in the spring of 2017, I enrolled as the first PhD student in the Marine Institute of Memorial University’s Fisheries Science Program. By the end of that summer, I was spending most of my days exploring the Big Land by truck, plane, and boat. Sitting in my office at the Labrador Institute one August morning, I received a phone call from an unknown number.

“They’re here, they’re spawn… they’re spawning!”

The voice was broken and hard to pick out over the satellite connection.

“Errol, is that you? The fish are there?”

Errol Andersen is the lead Conservation Officer for the Nunatsiavut Government, and I had worked closely with him over those last few months.

“Yes! The capelin are spawning! Best get on that plane!”

I flew out a couple of hours later from Happy Valley-Goose Bay to the Inuit community of Makkovik, Labrador.

Let’s take a more detailed look at capelin: what are they and why are they important? Across the North Atlantic, this little fish supplies more than just food for larger predators. Capelin have long been a central part of not only the marine food chain, but Labradorian culture.

In the early 1900s, it wasn’t long after the spring break-up in mid- to late-June that capelin would line the shallow, sandy beaches when the tide was low and easterly winds blew strong.1 These capelin, known as bay capelin, were the first to spawn, and would normally be chased to shore by cod, tom cod, and seals. They were followed in July by larger sea capelin that moved into the bays from outside islands. I’ve come to learn after my time in Northern Labrador this past year that “outside capelin” refer to those that spawn in deeper water away from beaches and are much larger than the bay capelin that still use beaches as their main spawning grounds.

Capelin was a secondary resource for Inuit in Labrador pre-settlement, and continued after the 1960s to be a dietary staple along with other fish including char, tom cod, salmon, and brook and lake trout. But nothing seems to beat the excitement of the capelin harvest, as their spawning time ashore is sporadic and short-lived. People living along the coast are no strangers to the usages of capelin and the excitement that comes with their harvest:

We dried a lot for dog food when they’d come in. They washed ashore in big piles sometimes. We’d get a rake and just rake them in so the water wouldn’t reach them. Spread them out with a rake for dog food.

(Chelsey Webb, n.d., Nain, in Our Footprints are Everywhere, pp. 128)

When I was about four years old up in Nutak [later resettled to Makkovik], I woke up one morning, thunder and lightning, pouring rain, and I shouted out to Mother and father, no answer, nobody in the house only me. So I got up and looked out the window and they were all down the beach. This is what they were doing – fishing the capelin. I never even bothered getting dressed, just my pyjamas, I ran down and here was this silvery little fish all over the place, here, grabbing by the handfuls, throwing rocks. Imagine – you wake up in the middle of the night, all alone, about four years old, only one in the house, and didn’t know what was going on. This is what it was! Someone sung out and said, “The capelin are coming in!” and of course, everyone in the community had to go.

(Ian and Dave Massie, 1930s, Nain, in Them Days, pp. 72)

Although local fisheries have long been customary, the commercial capelin fishery didn’t fully developed until the 1970s. Uses ranged from dried snacks, bait, and fertilizer to a lucrative export business, where female roe-bearing capelin were sold to Asian markets. In 1991, the capelin stocks crashed, and although catch numbers have improved, they have never returned to 1990 levels. Recently, capelin are even less predictable in terms of spawning timings and locations across Labrador, piquing interest from community members, fishermen, scientists, and managers.

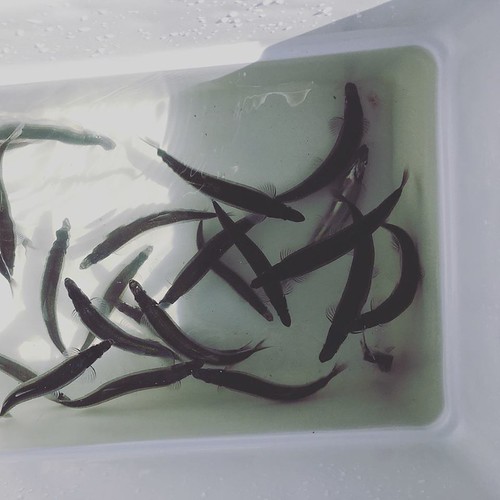

When I landed in Makkovik in the late afternoon, Errol and I set out across the bay to where he had witnessed the spawning event. The capelin had seemingly disappeared, gone out with the tide. The following morning, with sampling kits in hand and fishing gear aboard, we set out across the bay. And the capelin were back… but we couldn’t reach them! When capelin spawn in deeper water, they are packed in dense mats, tight to the sea floor. The boulders were too numerous around the matted fish for our trap to seal around them. It was only when a grumpus (local name for minke) whale started feeding that the spawning fish were disturbed and pushed closer to the surface. Errol cast the net, and only a short time later, we left with our sample of 25 spawning male capelin. This would be the last sample collected for the summer, and our only one for Labrador in 2017. I left Makkovik that August with a belly full of capelin graciously shared by community members, and a plan to return for the 2018 field season.

My research focusses on capelin fisheries, both commercial and social, throughout Labrador as well as the Quebec Lower North Shore region, in order to generate information that will lead to improvements in capelin management. I will be co-launching an observer network alongside our Indigenous and industry partners across both the South and North coasts of Labrador; all community members are encouraged to participate! I will also be conducting interviews with fishers and elders in order to map out current and past spawning locations later this year.

For more information on our project, and how to get involved with my work specifically, please visit https://about.me/cboaler.

Notes

1 Labrador Inuit Association. (1977). Our Footprints are Everywhere: Inuit Land Use and Occupancy in Labrador. Canada: Dallco Printing Ltd.

2 Massie, D. (2016). Them Days: Stories of Early Labrador 40(1). pp. 7.