Aldrich Interdisciplinary Lecture 2002

Preparing our Universities' Future Faculty:

A Challenge for our Graduate Schools

by Robert J. Giroux

President Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada

February 27, 2002

Introduction

Thank you ladies and gentlemen.

Let me first take a moment to thank Dr. Jablonski for his invitation to speak to you today. These are exciting times for the academe, replete with challenges and opportunities. AUCC has been doing some very interesting work in the past several years on the various factors that will trigger change in our universities in the future. In fact, these changes have already started to occur. What I would like to do this afternoon is sketch for you the context in which these changes are occurring and why graduate schools are so vitally important not only for the future well-being of the graduates and the university sector but also for the Canadian economy.

In many ways, my job is the easy one: outline for you what are the challenges, but also the opportunities, that lie ahead. The appetite of our rapidly evolving knowledge-based society for increasingly qualified and creative thinkers is insatiable. And in academe, the expected turnover of faculty in the coming decade will create a huge increase in the demand for university professors and researchers.

I will focus my remarks today first on why universities will need to dramatically increase the production of PhDs and, second, on how we can all work together to meet this challenge of renewal. Before I do so however, let me turn briefly to the conditions that have set in motion the dramatic changes we expect in academic labour market conditions.

The changing faces(s) of academe: building the new professoriate

Over the last few years the AUCC has focussed much of its research efforts on the tremendous challenges confronting Canadian universities in the coming decade as they renew their faculty. The efforts to understand and quantify faculty replacement needs began in the early 1990s, but the urgency of the messages escalated greatly in the fall of 1999. Since then, our research has spawned a host of other studies which essentially arrive at the same kinds of conclusions. Studies from the Laurier Institute in British Columbia, to the Ontario Faculty Association (OCUFA) to the Council of Ontario Universities all conclude that there will be a tremendous increase in the need to replace a growing number of faculty who are now reaching "normal" retirement age. When university presidents met three years ago in Brandon, Manitoba we estimated that, over the period 1999 to 2010, Canadian universities would need to hire almost 32,000 new faculty.

We also listed, from our research, the factors that led to those projections. When presidents met in the fall of 2000 in Calgary we discussed again the challenges that universities will face to renew their faculty in the decade ahead. In the fall of 2000 I also met with the Canadian Association of Graduate Studies (CAGS) to highlight the renewal challenges that are most relevant to deans of graduate studies. The CAGS conference in the fall of 2001 explored how increases to student assistance would help increase graduate enrolment.

I would like to think that many of the concerns raised in these meetings have helped to highlight the vital importance of graduate education in the knowledge economy and society and have inspired some of the recent initiatives that address these issues. For example, the Canada Research Chairs Program introduced in the Federal Budget, in February 2000 was designed to assist universities attract, retain and repatriate some of Canada's most productive researchers as well as some of the highly talented recent graduates who have the potential to lead our research efforts in the decade ahead. Recent growth in granting council funding to provide more and larger research grants are also instrumental in keeping research talent in Canadian universities. While the recently announced funding for the indirect costs of research is only indirectly related, it is nonetheless a vital recognition of the importance of providing a well resourced research environment. These indirect costs will be important in providing more employment opportunities for graduate students in supporting and engaging in a wide variety of research activities in Canadian universities.

The recently released papers from Industry Canada and HRDC on Innovation and Skills and Learning both speak to the need to do more to encourage greater participation in graduate programs. While the growing human resource needs of the university sector are recognized in both papers, it is also clear that both Industry Canada and HRDC expect demand for masters and PhD's to grow strongly from other public sector employers and from the business sector.

The demand for graduates will rise to unprecedented levels if federal and provincial government policies continue to encourage greater investments in research throughout our economy. In recent years Canada has remained in 15th place internationally in terms of the country's relative levels of investment in research and development as measured by the so-called GERD to GDP ratio (that is: Gross Expenditures on Research and Development as a percent of Gross Domestic Product). In the 2001 Speech from the Throne, the federal government stated that Canada should seek to move to 5th place by 2010. Provincial Science and Technology Ministers last summer strongly supported this policy objective. As a consequence of the strong consensus that has developed around achieving this lofty objective, there is every reason to expect that past trends in the demand for university graduates significantly understates the kind of growth in demand that is probable over the coming decade. This is especially the case for those with graduate degrees, given the research experience they receive throughout their graduate programs.

In short, it would appear that many signals point to a very encouraging decade ahead for those involved in graduate studies. However, there are a number of challenges that must be overcome to realize this potential.

Challenge one: convincing potential students to enroll in graduate programs.

In recent years students have received mixed messages about the potential benefits of enrolling in graduate programs. Indeed graduate enrolment leveled off through the mid 1990s. Moreover, there was an increasing amount of noise about impending shortages in academe, yet the number of people being hired did not match this rhetoric. This was not the first time that an "industry" has documented concerns about impending shortages of qualified personnel without following through with increased hiring. Indeed, many of you may have heard such cries before and therefore be somewhat skeptical about the magnitude of the real needs.

The low demand in the mid 1990s can be explained. For most of the 1990s, Canadian universities were stuck in retrenchment mode as they were faced with unprecedented cuts in government funding. Most universities were therefor looking for ways to reduce expenditures, including introducing early retirement programs. As a result of the financial pressures, universities could not replace all departing faculty. In fact, in the mid 1990s universities were replacing only half the faculty who left academe. Obviously, this reduced employment opportunities for students earning their PhD's in that period, sending negative signals to those still in or considering enrolling in a PhD program, a factor that contributed to declining interest in doctoral programs.

While the demand within academe faltered at the end of the decade, the overall demand in the broader labour market for graduates from master's and doctoral programs grew rapidly during the 1990s. Let me just put the growth in demand in perspective. In December 2001 there were one million jobs filled by graduates from master's and doctoral programs compared to just 600,000 at the beginning of the decade – a net increase of 400,000. Moreover, throughout the decade, unemployment rates of graduates from master's and doctoral programs were half the rates of those who have not completed postsecondary study and well below the rates of other postsecondary graduates. Average rates were near or under four percent for most of the last year. The income levels of graduates from master's and doctoral programs also grew in the 1990s, again indicating growing demand for graduates in the labour market.

It is therefore clear that the labour market was sending out very strong signals to potential students. Indeed the growth in employment levels exceeded the 300,000 new graduates degrees earned from our universities over the decade. To help fill this shortfall, during the 1990s Canada welcomed over 100,000 immigrants who had already graduated from master's and doctoral programs (often in their country of origin). These labour market trends combined with government policies designed to increase research efforts in our economy bode well for the future demand for graduate degrees. These trends certainly help to explain why we feel demand in sectors outside academe are such important drivers of graduate education and why the competition for graduates will continue to grow over the coming decade. At the very least, they should help convince potential students of the benefits of graduating from master's and doctoral programs and eliminate any confusion from the mixed messages emanating from the academic labour market in the mid-1990s.

Challenge two: Meeting the growing demand in academe.

We are also now convinced that demand within academe will also be a major factor driving demand for PhD's in the decade ahead. There are three reasons driving faculty hiring: first, AUCC projects undergraduate enrolment increases of 20 to 30 percent over the next decade and universities will need to hire more faculty to teach these students; second, there will continue to be a large number of faculty retirements over the next 10 years; and third, in order to address some of the serious erosion that has occurred, universities will need to replace the 4,000 faculty they've lost since 1992 and that are necessary to make improvements to the quality of educational and research services offered at our institutions.

All three factors will place strong pressure on universities to begin rebuilding their ranks through replacement and growth.

But will the resources be available to do so? Provincial government funding is one of the main uncertainties in faculty renewal. It will be very difficult for institutions to grow if additional resources don't flow into the institutions first. There were positive signs in 2000 and early 2001 that some provincial governments turned a corner and started to reinvest in higher education. We must ensure that these directions will continue especially in the wake of September 11 and with the economic slowdown with which it coincided. Let's look at some of the projected changes in a little more detail.

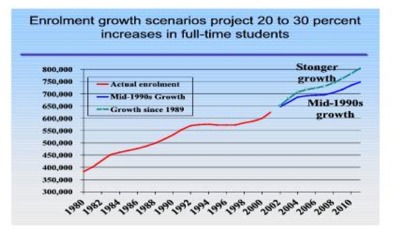

Enrolment is arguably the most important external factor affecting faculty renewal. Student enrolment increases will have a major impact on the need to hire more faculty over the coming decade. Historically, the number of faculty has not kept pace with student growth because not enough resources were invested. However, we hope that in the quest to improve quality we can attract the resources necessary to reverse that trend. We have been predicting strong enrolment for several years and there are now signs that it has begun. Our fall enrolment survey shows enrolment in the current school year has increased by 45,000 over the last three years. This is well ahead of the pace that was expected and now puts us on a path that would see full-time enrollment grow from about 625, 000 in the fall of 2001 to between 750,000 and 800,000 by the fall of 2011. This means that universities will need to hire even greater numbers of faculty if they want to restore an acceptable level of student support through teaching, research and scholarship.

Why are enrolments expected to grow? Enrolment will grow because of population push and participation pull.

The children of baby boomers—the baby boom echo—are just beginning to reach the age when many will start university. The numbers in this cohort will continue to grow over the next decade.

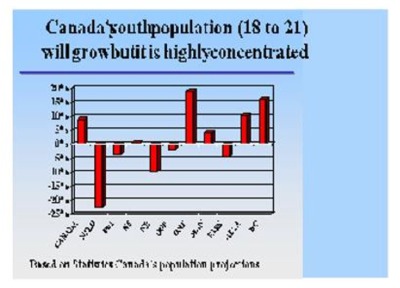

But this growth will be unevenly distributed across the country. As you are no doubt aware population in the youth cohorts in Newfoundland and indeed in most provinces east of Ontario expect to have fewer 18 to 21 year-olds at the end of the next decade than they have now.

As the chart shows, strong growth is expected in Ontario (19 percent), Alberta (10 percent) and BC (16 percent). These three provinces are pushing the national figures up. Clearly, capacity may need to be expanded in those regions of the country where the combination of population and participation increases place new strains on existing universities.

However, past enrolment trends suggest that strong enrolment growth is possible even in the face of demographic declines. Such was the case between 1981 and 1991 when population in the 18 to 21 age group declined by almost 20 percent nationally, and by more than 10 percent in every province, while university enrolment from that age group increased strongly in every province, with a national average of almost 30 percent.

Therefore, even in provinces where population declines are expected, a relatively small increase in participation rates would offset a demographic decline. Of course, with the depth of the population decline in Newfoundland, Memorial will face a bigger challenge to maintain current enrolment levels than in other parts of Canada.

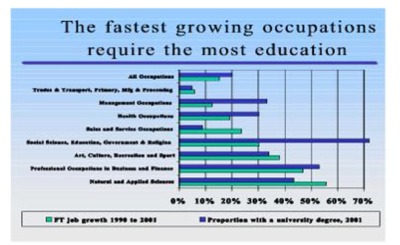

So why are we projecting increases in participation? There are a host of interrelated factors that affect university participation rates. Despite the reservations of many faculty members about focusing the university on preparing students for the labour market, it is clear that students, with the strong influence of their parents, increasingly consider labour market factors in their decisions to attend university. More importantly, in an increasingly knowledge-based society, the fastest growing occupations are those that require a university degree. This chart confirms that the fastest growing occupations in the last dozen years also require the highest level of education – 30 to 70 percent of the employees in these occupations have university degrees.

Another reason for expected increases in participation rates is that children are far more likely to attend university if one or both of their parents have completed a university degree. Many more "baby boomers" have completed degrees than the generation that preceded them – 17 percent of today's 45 to 54 year-olds hold a degree compared to just 6% fifteen years ago. Since many of the boomers' children are about to complete secondary school, it stands to reason that this group will cause significant upward pressure on participation rates.

We have developed two growth scenarios. The first is tied to rates of change in participation rates experienced between 1993 and 1999, the slowest average growth in participation rates experienced in the last thirty years. The second scenario is based on the change in participation rates since 1989. In effect, both projections are constrained by the lack of growth in capacity in the 1990s and therefore both could be quite conservative. It is important to note that the projected changes in participation scenarios are quite small. For example, in the 18 to 21 cohort participation rates rise from 18.3 percent currently to about 21.2 percent under the limited growth scenario and to about 22.3 percent under the second and stronger growth scenario. In other words, even in this latter case university participation is still not expected to surpass one in four. Participation rates for those 22 to 24 are projected to rise from 13 percent to 15 percent under the first scenario and to 16 percent in the second scenario.

The impact of these changes in participation combined with similarly small changes in the participation rates of other age cohorts is shown in the next chart. Total full-time enrolment is expected to grow from the current level of 625,000 students to between 750,000 and 800,000 – and as the chart shows the growth we have been projecting has begun. Look at the numbers for the period 1999 to 2002.

What is behind this recent surge in participation? The knowledge economy has produced an incredible change in the distribution of employment. Human Resources Development Canada officials project that by 2004, 25 percent of new jobs will require a university degree, up from under 17 percent of current jobs. This kind of growth in employment opportunity will encourage even higher levels of university participation.

In fact, with the added impact of the double cohort in Ontario, growth in faculty numbers there will have to be much more rapid in the first half of the coming decade than in the latter half. For Canada as a whole we estimate that the growth rate in faculty would have to be in the order of 3.5 percent per year until 2005, then slowly decline to about one percent growth by the end of the decade. In 2011 there would be just over 45,000 faculty, from close to 34,000 currently.

Growing retirements will also drive hiring requirements

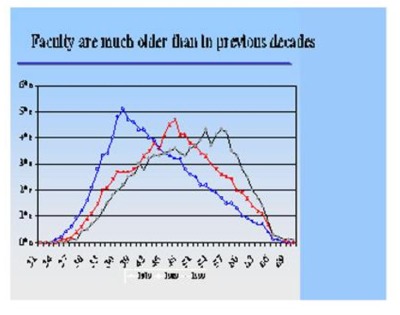

Enrolment growth is not the only determinant of our hiring needs. Due to the age profile of current faculty members, growing retirements will also drive growth in hiring requirements over the coming decade. We can demonstrate the aging of our faculty by tracking the big bulge that moved from their late thirties in 1976 to their late fifties in 1999. Within a decade most of the bulge should moved completely through the career cycle. The upshot of this is that over the coming decade the need to replace departing faculty will increase.

Almost one-third of current faculty are over age 55 and an additional 20 percent are already in their early fifties. Based on historical attrition trends, there is very little doubt that Canadian universities will need to replace almost 20,000 of our current faculty members over the next 10 years.

We can no longer wait to see if the anticipated change will come about. It is here. There are more students than ever. And our academic staff has never been older and never more certain to leave our institutions in greater and greater numbers. In fact, over the last 18 months we have seen a very significant increase in advertisements for faculty positions in our University Affairs publication. This provides one indicator of the current growth in demand for faculty.

The combined impact of growth and retirements will significantly increase the hiring requirements of universities. Universities will need to hire an additional 10,000 to 12,000 faculty over the decade to meet enrolment growth and, as stated before, another 20,000 to cover retirement. Combined, the needs are in the order of 30,000 faculty or about 3,000 per year, as the following chart shows.

The first column of the chart also shows the number of faculty universities would need to hire if they were to recoup the 4,000 faculty cut in the mid-1990s. The second column shows that even more faculty would be required if universities hoped to reduce student faculty ratios to the levels that existed at the beginning of the 1990s.

The mix in demand for human and physical resources will vary from province to province and from institution to institution, but expansion overall is required. Enrolment growth of the magnitude projected can only occur if additional resources are pumped into the system. But enrolment growth and replacement demand of these magnitudes have important implications for universities with graduate programs -- in the short-term it means finding ways to both encourage more students to enroll in graduate programs as well as finding ways to increase the number of graduates to join your university to meet the rapid rise in demand for faculty.

Challenge three: Increasing the supply of qualified candidates

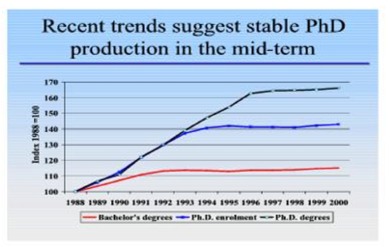

The third challenge we face is that of increasing the supply of qualified candidates. It is a major challenge if one looks at the next chart which shows that our PhD production is currently flat. There are only a few ways to confront this challenge. We can increase our domestic production of PhDs. Or, we can recruit more aggressively on the international academic labour market.

There are a number of factors that need to be addressed in order to expand our graduate programs so as to meet the needs in all labour markets that require our most highly qualified PhD graduates.

As you well know, there are no quick fixes. Moreover, recent trends are working against us. Bachelor's enrolment levels did not grow at all through the mid-1990s. This, of course, has had an impact on bachelor's and master's degrees granted and subsequently on the number enrolled in PhD programs. And with the increasing demands on the new economy, bachelor's and master's graduates could find challenging jobs in the market. PhD enrolment has not grown since 1994 and the number of degrees granted has remained constant since 1997.

Given the time it takes to complete a PhD program, stable enrolment signals that relatively little change in the number of PhD degrees can be expected over the next five years. Clearly, increasing our PhD production is a long-term solution. It will not help us that much in the short term.

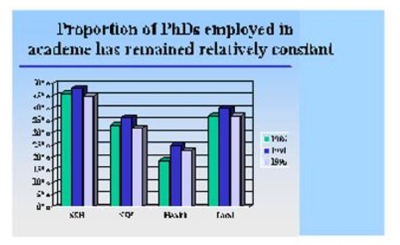

The demand for graduates outside academe will only serve to heighten the challenge of attracting more of our graduates into academe. It is increasingly clear that a career in academe is only one occupational choice for our graduates. As the Census data indicates universities do not have a monopoly on PhD graduates. Indeed, other sectors employ the majority of our graduates – historically between 60 and 70 percent. Our challenge is to attract a greater share back to academe. But, even if we were successful in meeting this challenge in the short term, with the changes that are taking place in an increasingly knowledge-based economy it is highly doubtful that the demand for PhDs in other sectors will fall. In the longer term it is likely that growing demand in all sectors will mean that graduate programs will have to grow at least as fast, if not faster than the 20 percent plus that is expected at the undergraduate level.

Seizing the opportunity

For this to happen, we will need to seriously turn our attention to creating the nurturing environment needed for successful graduate studies. Much of that challenge is internal to universities. I understand that CAGS is working on a study analysing some of the factors affecting the duration of studies and completion rates. I applaud those initiatives and suggest that we all work closely with both industry Canada and HRDC to ensure that the measures they are proposing will assist universities in meeting these goals.

Part of the challenge of convincing undergraduate students to move on to graduate studies will be to communicate better the rewards they can expect from longer studies. If only from the economic perspective, the case is compelling enough. Income premiums and employment levels are significantly higher the longer you study. This has to be said loud and clear. Further, the funding environment for university research has changed dramatically and positively over the last three or four years. This is a plus. Much of the answer to the challenge of how to create those right conditions I mentioned earlier can be found at that level.

Certainly the Industry Canada and HRDC papers both recognise the challenge of increasing enrolment in graduate programs and those papers suggest increased student aid will be critical to meeting this need. Those papers suggest that enrolment in graduate programs should grow by about five percent per year over the next ten years and that the federal government can contribute to that growth by providing additional scholarships, other student assistance and research grants.

However, a rapid and large expansion of masters and PhD programs cannot be achieved but simply adding students at the margins – that is filling empty seats in graduate classrooms. Most universities would be quite happy to either start or expand their graduate programs. On the other hand, these programs are generally far more expensive to run because they require more extensive interactions between student and faculty, both in the classroom and in the labs. Mentoring students, providing advice on their research papers and theses and involving students in faculty research activities are but a few of the additional faculty responsibilities that make graduate programs more labour intensive.

In short, the need to expand graduate programs has a disproportionately higher impact on the need to higher more faculty then does enrolment growth at the undergraduate level. And this means increases to the basic core budget of universities. This is where provincial governments have an impact. Moreover, with the expected growth in undergraduate programs, many universities can expect very difficult internal resource allocation decisions and pressures from their respective provincial governments to ensure that access to undergraduate programs is not unduly restricted.

More is expected of universities – greater access to both graduate and undergraduate students, producing more highly skilled graduates, conducting more research, and more interaction with their local communities as well as with the business community and governments generally. I believe that universities can meet the multitude of demands only if they are well-resourced. Some very interesting initiatives have been put in place and others are currently being proposed. We need to build on initiatives like the Canada Research Chairs Program, like the Canada Foundation for Innovation, Y to ensure that our universities have the capacity to provide high quality teaching, research and community services. In short, providing these services in a healthy environment is the only way we can hope that universities can fulfil their role as drivers of economic and social prosperity.