Rooted in place

Great Gallows Harbour is, or was, at “the back of the bended knee” of the Burin Peninsula. It is one of many outports that vanished from Placentia Bay following government resettlement in the last century. Located at the mouth of Paradise Sound, it was home to 10 families, accessible only by boat, and a paradise for a young Leslie Harris in the 1930s and 1940s.

Very few from those last Placentia Bay generations have lived in the place — or the world — where they grew up. Harris journeyed farther than most after 1945, when, as a teenager, he made his first schooner trip to St. John’s.

He earned a BA and MA from Memorial University and taught in schools throughout the province. He later completed a doctorate at the University of London. After working at colleges in the United States, he returned to Memorial in 1963, where he served as an assistant professor, head of the history department, dean of arts and science, vice-president (academic), and finally president from 1982 to 1990. He was the first Memorial graduate to become president — a milestone that symbolized the university’s coming of age.

His rapid rise through the administrative ranks was a testament to his abilities, recognized early in his career. Shortly after his arrival, Harris was responsible for the landmark 1967 report, The government and administration of Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Its sweeping recommendations — 38 in total — would substantially reshape the university’s academic and administrative structures and largely define the Memorial of today. His proposals included appointing academic and administrative vice-presidents; establishing new schools, such as graduate studies and physical education; creating new research institutes and departments, including commerce and political science; affirming departments as the basic academic unit; and recommending that the Board of Regents appoint the president.

But Harris was far more than an administrator.

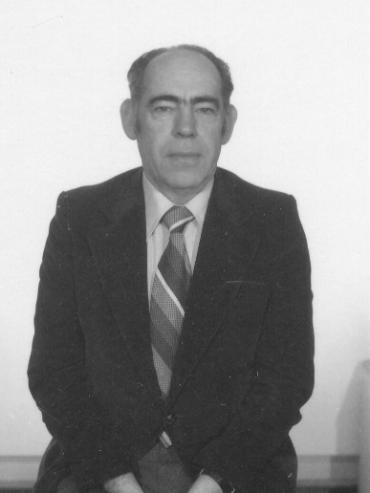

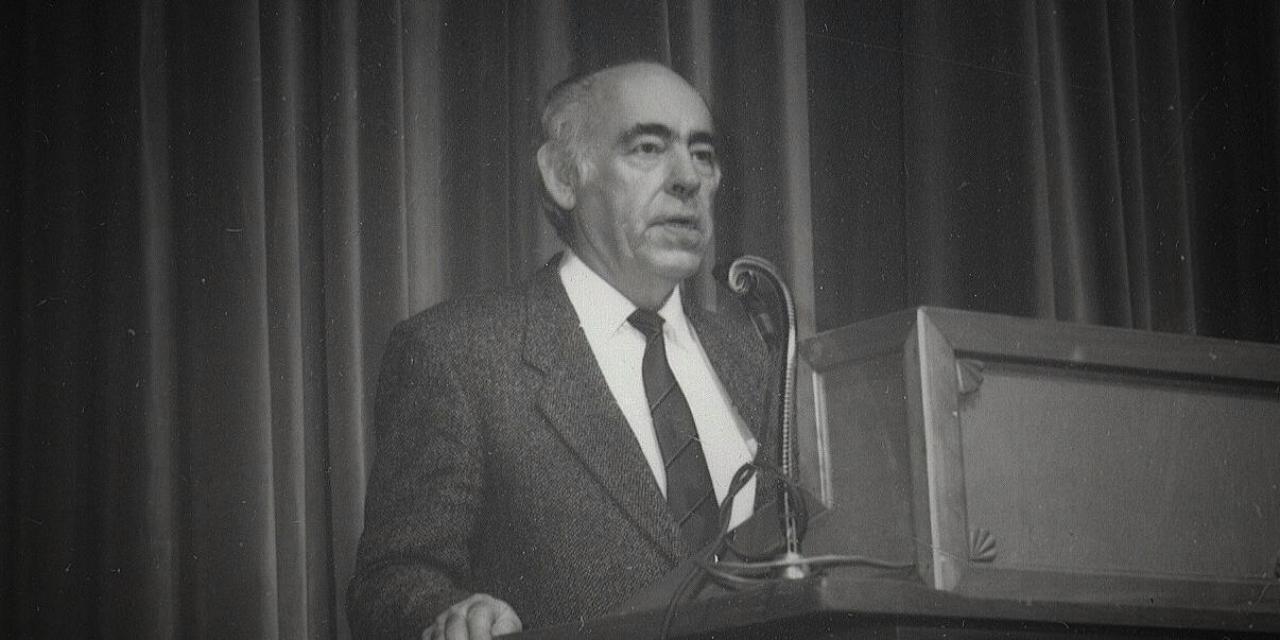

Dr. Leslie Harris was president of Memorial University from 1982 to 1990. Photo from Memorial University Archives.

He was instrumental in Memorial’s growing engagement with Newfoundland and Labrador’s culture and history. His support for building a research program centred on the study of Newfoundland society was central to his career. Under his leadership, the university developed the Folklore Archive, the English Language Research Centre and the Maritime History Archive.

Harris believed strongly in drawing intellectual strength from place — history, language and folklore — to make the university distinctive and attractive to students and faculty alike. He argued that Memorial’s research mattered because it affirmed local identity at a time of rapid modernization. As orator Shane O’Dea once said, “He made us think of our future in order that we might have one.”

Harris himself put it this way: “Newfoundlanders know ourselves far better than we have ever done because of the work of scholars at Memorial.” He also emphasized the reciprocal relationship between university and society: society needs the knowledge universities preserve and extend, and universities, in turn, depend on the support of the communities they serve.

Harris served the province and country in many capacities, including as member and chair of the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, director of the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada, chair of the environmental review for the Terra Nova offshore oil project, and chair of the Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage Fair.

Because of his reputation for leadership and impartiality, he was appointed in 1989 to lead the review panel on northern cod stocks — a full year before his retirement as president.

The cod crisis was not merely a scientific problem, but a deeply political, social and economic one. Harris brought cultural credibility and local legitimacy to the role, helping translate scientific uncertainty into policy-relevant advice focused on long-term sustainability. Describing modern fishing technology as “the greatest killing machine ever invented,” the panel concluded that northern cod stocks were being harvested beyond sustainable levels and that continued fishing at existing quotas posed a serious biological risk, though it stopped short of calling for a full closure.

Two years later, then-fisheries minister John Crosbie did exactly that.

Above all, Harris was of the bay — particularly Fogo Island, a “sea-smacked fringe of the continent.” There, he indulged his love of salmon fishing and berry picking and, according to Harris, found the best salt cod anywhere. Gordon Slade, who worked with him on the restoration of Battle Harbour, noted that Harris used the island as a reference point in shaping his understanding of the province, its history and its people.

Dr. Leslie Harris left a deep and lasting legacy at Memorial University. His influence spans academic leadership, institutional growth, expanded research capacity and the development of graduate programs.

But most of all, his legacy is one of public responsibility and community engagement. He helped define Memorial as both a rigorous academic institution and a public-serving university, deeply connected to Newfoundland and Labrador.