Voices from the past

In the 1960s, Newfoundland and Labrador was at a cultural crossroads.

The province had been a part of Canada for just over a decade. The resettlement program was underway. Politicians heralded modernity. And traditional ways of life were shifting quickly.

But at the same time, a new energy was emerging within the arts and humanities. Dr. George Story was at work on what would become the Dictionary of Newfoundland English. The Memorial University Art Gallery, then located in the Henrietta Harvey Building, was uniting visual artists, and Memorial’s Extension Service was embarking on the mission that would eventually lead to projects like The Fogo Process.

The seeds of what writer Sandra Gwyn would later call the “Newfoundland Renaissance” had been planted.

Into this cultural ferment arrived Herbert Halpert, an American folklorist whose life’s work became documenting and preserving the voices, music and customs that define so much of traditional outport life.

Dr. Halpert, born in New York City in 1911, was already a respected figure in folklore circles when he came to Memorial in 1962. He had studied under pioneering folklorists like Stith Thompson and Richard Dorson, and he brought with him a deep respect for the songs and stories of everyday working people.

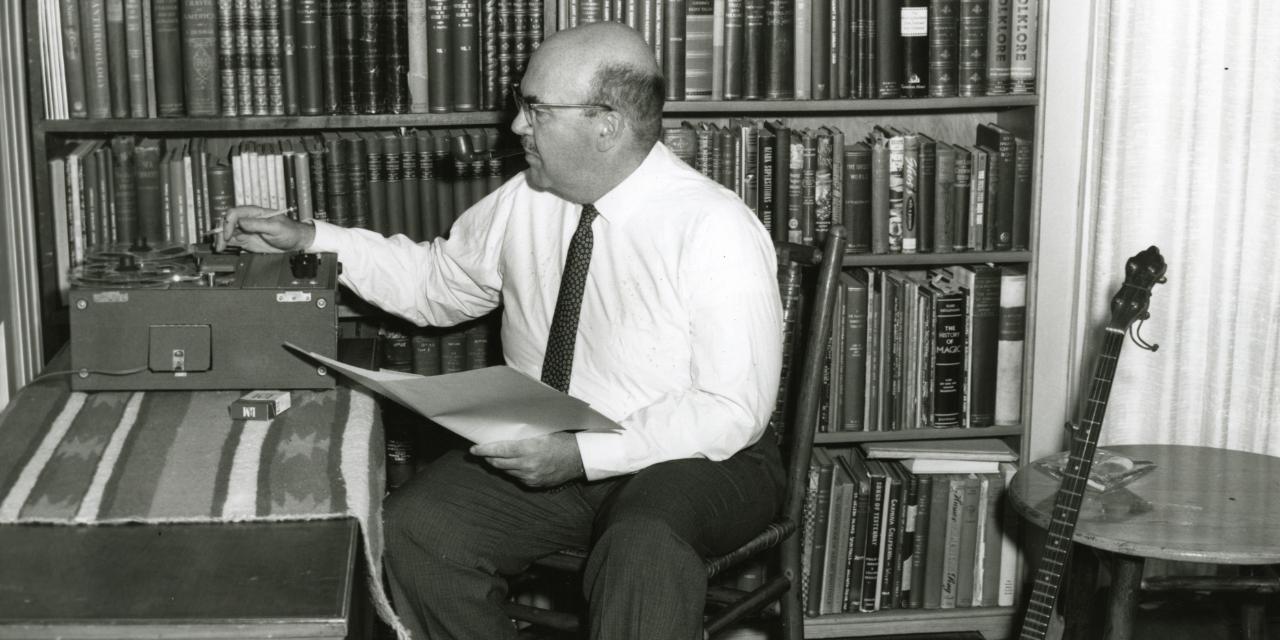

With reel-to-reel tape recorders, notebooks and a relentless curiosity, he and his students fanned out across communities, gathering songs, ballads, legends, riddles and oral histories that otherwise might have been lost.

He founded Memorial’s Department of Folklore in 1968, making it the first university in Canada — and one of the first in the world — to grant degrees in folklore.

The department became a global destination for students, scholars and researchers interested in vernacular culture, oral history and traditional knowledge.

And alongside his wife, Dr. Violetta “Letty” Halpert, he helped establish the Memorial University of Newfoundland Folklore and Language Archive (MUNFLA), which remains one of the most significant collections of folklore in North America.

Herbert Halpert working with a reel-to-reel tape recorder in Carlinville, Ill., 1960. Photo from MUNFLA.

What Halpert set in motion was not simply an academic exercise; it was a cultural safeguard. He understood that folklore was not just quaint entertainment, but a living record of how people understood themselves, their history and their world.

The timing of his work could not have been more important. As modernization and resettlement programs uprooted families from traditional communities, the very culture he was recording was being threatened.

But rather than allow traditions to vanish, Halpert and his colleagues helped preserve them, making them available for future generations of scholars, artists and cultural leaders.

Today the folklore archive houses over 50,000 audio recordings, 20,000 photographs and countless manuscripts, documenting the stories, songs superstitions and customs of everyday Newfoundlanders and Labradorians.

It’s a place where you can literally hear the voices of the past.

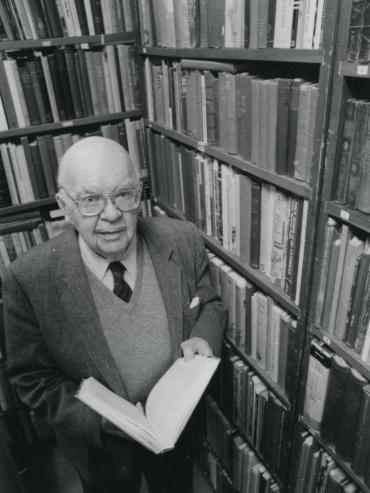

Dr. Halpert himself was a meticulous scholar, and his field notes are legendary for their detail. For him, folklore was living history.

He received recognition for his scholarship, but it might be impossible to measure his enduring achievement. As a repository of invaluable contents, the Folklore and Language Archive is still growing today, its holdings used by filmmakers, authors, community groups, students and academic researchers.

What he set in motion has become part of Newfoundland and Labrador’s cultural DNA.

Dr. Halpert passed away in 2000, but his influence remains woven into the province’s cultural life.

Thanks to his vision and persistence, Newfoundland and Labrador did not lose its traditions to the tide of modernization. Instead, those traditions became a resource — preserved, celebrated and renewed.

In many ways, he was both a witness and a catalyst, helping to ensure that the voices of the past continue to speak to the present.