In search of a legend

In The Odyssey, Homer describes Odysseus’s antagonist, Scylla, as having “six long sinuous necks outstretching before her.”

It sounds vaguely familiar even though the story was composed in the 8th or 7th century BC.

Fast forward a few centuries: in 1555, Olaus Magnus, archbishop of Uppsala, Sweden, referred to “monstrous fish on the coast or sea of Norway” and coined the word kraken (meaning an uprooted or stunted tree). He wrote: “Their forms are horrible, their heads square ... and they have sharp and long horns round about, like a tree rooted up by the roots.”

In Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Captain Nemo and the crew of the Nautilus have their famous encounter with a giant kraken. A giant squid also dwells in the lake at Hogwarts in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series.

The giant squid’s elusive nature and fearsome appearance have long made it a subject of legend and folklore. Many believed it to be a mythical devilfish until Dr. Moses Harvey, a 19th-century naturalist, obtained Newfoundland specimens that he sent to the South Kensington Museum in London. (In 1990, Dr. Fred Aldrich was named to the newly created Moses Harvey Chair in Marine Biology at Memorial — a chair created for him.)

So how did a renowned marine biologist become an international expert on what many believed was a mythological figure? According to Dr. Aldrich, “It always began with the ringing of the phone.”

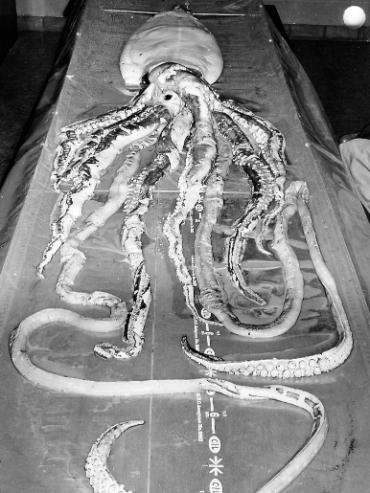

The first and largest of what would eventually become 15 giant squid to come to Memorial washed ashore near Conche on the Great Northern Peninsula in October 1964. The specimen weighed 330 pounds and measured about 30 feet in length. Its tentacles were each 21 feet long.

Fishermen hauling wood around Cape Fox saw the animal. They took it in tow and brought it to the bait depot in Conche. Knowing Memorial scientists were interested in the giant squid, the depot staff made a phone call.

Dr. Aldrich arranged for the animal to be flown to St. John’s. Two weeks of bad weather delayed the transport of the first giant squid seen ashore in 29 years.

In what was likely an homage to Dr. Aldrich’s discovery, the biology department’s float in the 1964 winter carnival parade was a giant squid.

Within weeks, a second — somewhat smaller and in poorer condition — specimen was reported from Chapel Arm, Trinity Bay. This, too, was brought to the university for examination. Despite its putrefied state, it was nicknamed Archi, after the scientific name of the giant squid, Architeuthis dux.

Three more were secured the following year, supporting Dr. Aldrich’s theory of a 30-year cycle. He postulated that giant squid appeared in Newfoundland’s coastal waters roughly every three decades, and the 1960s marked the current chapter in his hypothesized schedule.

Fred Aldrich came to Memorial University in 1961 as an associate professor of Biology. Photo from Memorial University Archives.

In time, a small group formed to aid Dr. Aldrich, which he called his “intrepid Squid Squad.” Regulars included graduate student Betty Way Johnson (medicine), her husband Harold (mathematics and statistics) and Claude Morris (biology).

On Nov. 10, 1982, the phone rang again. This time it was “the Whale Man,” Dr. Jon Lien. He reported that a giant squid had been spotted on the shore of Hare Bay. The Squid Squad rented a van, headed out and found a remarkably complete animal in excellent condition.

Affectionately nicknamed Davy Jones, the specimen was eventually donated to The Rooms where it is showcased in the Connections Gallery.

Dr. Aldrich became one of the world’s leading authorities on giant squid, and his reputation helped put Memorial on the map internationally in marine biology.

But he was so much more.

He was a professor, head of the Department of Biology, founding director of the Marine Sciences Research Laboratory (now the Ocean Sciences Centre), founding dean of the School of Graduate Studies and chair of the Presidential Task Force on the Future Role and Activities of the University in Ocean Studies.

In particular, he was profoundly dedicated to the School of Graduate Studies. The high standards he set have served the university and its students well. Despite his demanding expectations of both students and supervisors, he was, above all, a friend and even protector of his graduate students.

Alas, the living giant squid always eluded him, as it continues to elude scholars today. This did not hamper his distinguished career, which exemplifies higher education, animated as it is by a quest for discovery that may forever remain just out of reach.

And who knows? If Dr. Aldrich’s 30-year cycle is correct, it’s just about time for the giant squid to appear once again on our shores.