A man for all seasons

In 1956, he won the table-tennis championship at Memorial University. In 1978, he became a best-selling author. In 1987, he recorded an album of fiddle and accordion tunes.

He made ugly sticks. And he was known to hop on his boat and head to St. Pierre-Miquelon when he was out of rum. Not a problem as he was a master of small boats, even in the fog.

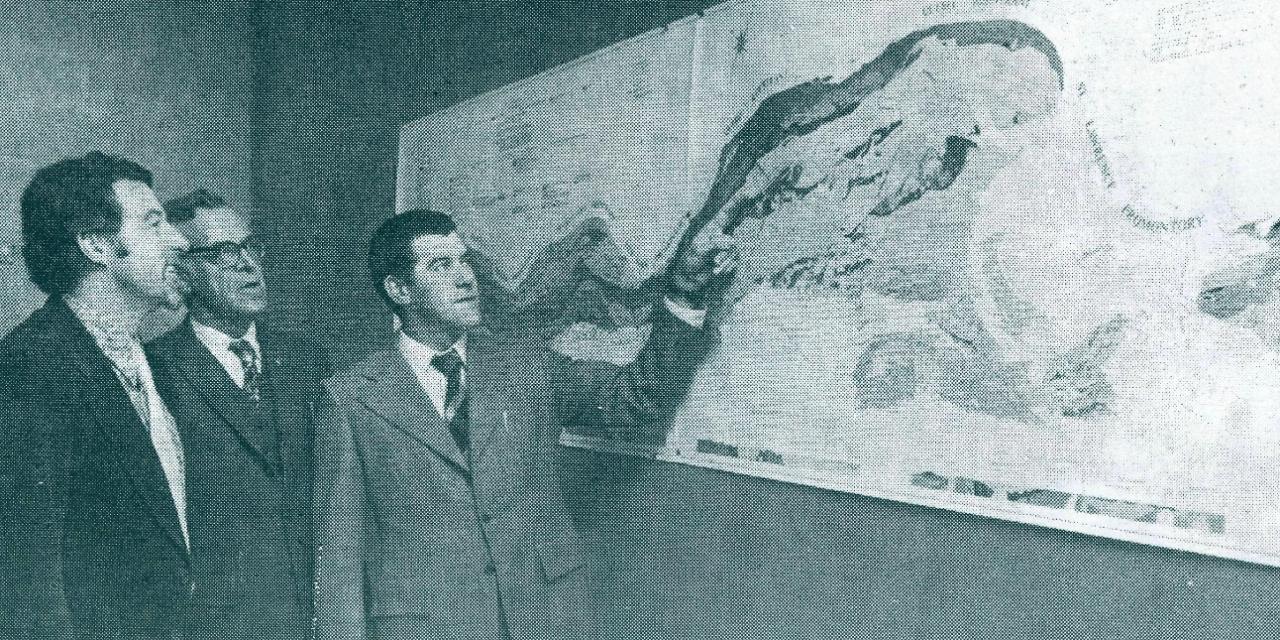

He was also an artist, of sorts. In the Earth Sciences building on the St. John’s campus, a huge map depicts the entire North American Appalachian mountain chain from Alabama to Newfoundland. When the illustrator stored 10,000 copies of that map in his living room, he had to buy jacks to shore up the floor from collapsing under the weight.

Dr. Harold (Hank) Williams, called the greatest Appalachian geologist of his day, created that map in 1978. It was known in the geology world as “Hank’s Map” and is still used today.

Dr. Williams also advanced a groundbreaking concept – the theory of colliding super-continents. He helped transform the notion of continental drift into the theory of plate tectonics. In noting how mountain belts such as the Appalachians arise, he described the evidence for Iapetus, the predecessor of the modern Atlantic Ocean. A sampling of rocks leading to this analysis is preserved and protected in Gros Morne National Park of western Newfoundland.

As he would later say, “When you open up the ocean, something’s got to keep the devil out, so you fill it up with magma rocks.”

The map also provided an explanation for why there are mineral deposits in mountains and a framework for geologists to focus their search for specific types of deposits, leading to discoveries such as Duck Pond mine

Under his auspices, Gros Morne National Park received UNESCO World Heritage status and Memorial was established as a leader in earth sciences research.

Dr. Williams explains details of his famous map to Dr. David Skevington and Dr. M.O. Morgan in 1978. Photo from the Gazette.

Dr. Williams was the first person to receive both a bachelor’s degree and master’s degree in geology from Memorial.

After earning his PhD and working for the Geological Survey of Canada, he returned to Memorial in 1968 as a faculty member where his list of firsts continued.

He was the first person appointed Alexander Murray Professor and University Research Professor and was one of the youngest fellows of the Royal Society of Canada when he was inducted in 1972. In 2015, he was posthumously inducted into the Canadian Mining Hall of Fame.

A former colleague quipped that Dr. Williams probably cut and walked more bush lines than anyone else on Earth. And having mapped over half the island of Newfoundland, it’s no surprise he was known for his cook-ups, which no doubt included fresh salmon in season since he was chided for wanting to eat it morning, noon and night. But any local delicacy would do – bottled moose, seal flipper or stuffed squid.

The meal would include stories as he was a gifted raconteur. He might provide music on the fiddle, banjo or guitar (he was known as “Hank” for his music wizardry). And there was a better-than-good chance he’d have a good laugh at awkward junctures.

Dr. Williams had many passions. He was a true, robust and loyal Newfoundlander. He loved geology, fieldwork, map making, playing Newfoundland music, storytelling and Dominion Ale.

Most important to Dr. Williams was communicating his work to the public, whether it was Prince Edward on a royal visit or visiting students in the Shad Valley Program. His excitement for his work, combined with his charisma, pulled you in to want to hear and learn more.

In fact, it was his’s love for what he did that inspired Paul Johnson to create the Johnson Geo Centre.

Dr. Williams wasn’t just an international superstar in the world of geology, and he didn’t just produce a new generation of geologists. He changed the way the world looks at rocks.

He was a man for all seasons.