The blueprint

It was April of 1925 and Levi Curtis, one of the founding trustees of Memorial University College, was setting sail from St. John’s with one objective.

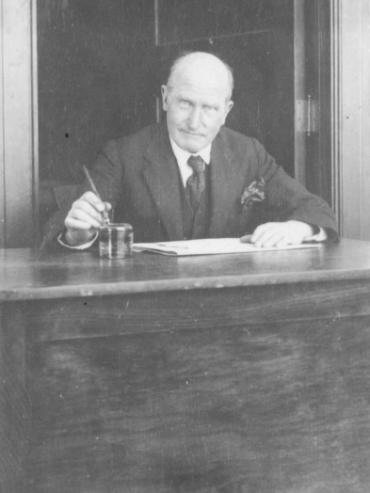

His quest was to track down John Lewis Paton, who had recently embarked on a speaking tour across Canada, and convince him to become Memorial’s first president.

There was no guarantee that Mr. Curtis would find him in time or if Mr. Paton would even consider the offer.

But the founding trustees were well versed in the educational trends and innovations of their time. They knew of Mr. Paton’s accomplishments and saw in him the embodiment of everything they envisioned for their fledgling university college.

Weeks later, having travelled halfway across the continent, Mr. Curtis finally caught up with Mr. Paton in Winnipeg, Man.

Somewhere in that prairie city, Mr. Curtis outlined the vision of a university college on the edge of the North Atlantic.

On April 26, 1925, Mr. Paton sent a telegraph to St. John’s accepting the position as president of Memorial University College.

Mr. Paton was born in Sheffield, England, in 1863. He was educated in both Germany and England and entered St. John’s College, University of Cambridge, in 1886.

He started his teaching career at Rugby, a prestigious private school in Warwickshire, and then became headmaster at the University College School in Hampstead, London, in 1898.

In 1903, he accepted the position of high master at Manchester Grammar School, a position he would hold until his retirement in 1924.

As a headmaster, in an age when headmasters were notable public figures in the United Kingdom, Mr. Paton was, in many ways, a rarity.

Even public schools in Mr. Paton’s time were somewhat exclusive. They maintained an air of social superiority, where young people were educated within a narrow curriculum and prepared for the most prestigious universities.

But he believed in expanding the curriculum to nurture the whole individual. He believed in community service and the democratic idea that the pathways to higher education should be opened for everyone.

While these beliefs were not entirely radical for their time, the degree to which Mr. Paton put his beliefs into action was notably uncommon.

He was known for engaging with his students, taking a keen interest in their backgrounds and plans. He was a pioneer in extramural activities, expanding athletic, volunteer and arts programming. He was one of the first headmasters to organize foreign exchanges, taking students on walking excursions in France, Italy, Germany and Norway.

By the time he retired in 1924, he was a renowned educationalist. In 1925, the Canadian National Council of Education brought him to Canada to lecture at universities and schools across the country.

And that’s when Memorial’s founding trustees seized their opportunity.

Memorial University College faculty in 1933. Left to right: C.A.D. MacIntosh (engineering); Muriel Hunter (Spanish); Allan Fraser (history, economics, political science); Monnie Mansfield (registrar); Albert Hatcher (math); Paul Lovett-Janison (chemistry); J.L. Paton (president, classics, German); Reginald Harling (physics); Sadie Organ (math, library); Alfred Hunter (English, French); Helena McGrath (classics, English); and Fred Sleggs (biology). There is one unidentified faculty member only partially visible behind Hatcher. Photo from Memorial University Archives.

Mr. Paton’s presence immediately established Memorial’s credibility.

But beyond his qualities as a teacher, administrator and leader, it was his unimpeachable character that would come to define the ethos of the young university college.

He saw no division between the campus and the community. He believed that when the people of Newfoundland and Labrador looked to Memorial, they should see their strength, values and aspirations reflected.

His convictions defined his actions. In the recollections of everyone whose lives he touched, he was remembered for his charitable nature and unending kindness to all.

When a student fell ill, they could expect to find a bag of oranges or grapes hanging outside their doors.

During the holiday season, he could be seen trudging through snow with a sack flung over his back delivering gifts to students and colleagues or to the orphanage or prison.

His famously long walks around town were made longer by his tendency to stop and help people in the community with their chores.

He would gather students together on the weekends and work with them to tend to the college grounds, which they called “The Barrens,” nurturing the sparse grass and planting shrubs and trees.

To ensure that students could remain in school, he began building a scholarship fund, and when a gifted student experienced financial uncertainty he would ensure they found the necessary funds.

Mr. Paton retired from Memorial in 1933. He returned to England and corresponded with his former students for the rest of his life.

He died in Beckenham, England, in 1946.

Due to his incredibly charitable nature, Mr. Paton never acquired great wealth. He maintained a spartan existence his entire life and often encountered financial difficulties. Even so, he managed to bequeath another $500 dollars to Memorial’s scholarship fund in his final will.

To this day, the library at Manchester Grammar School is called the Paton Library. On the St. John’s campus, Paton College is named in his honour.

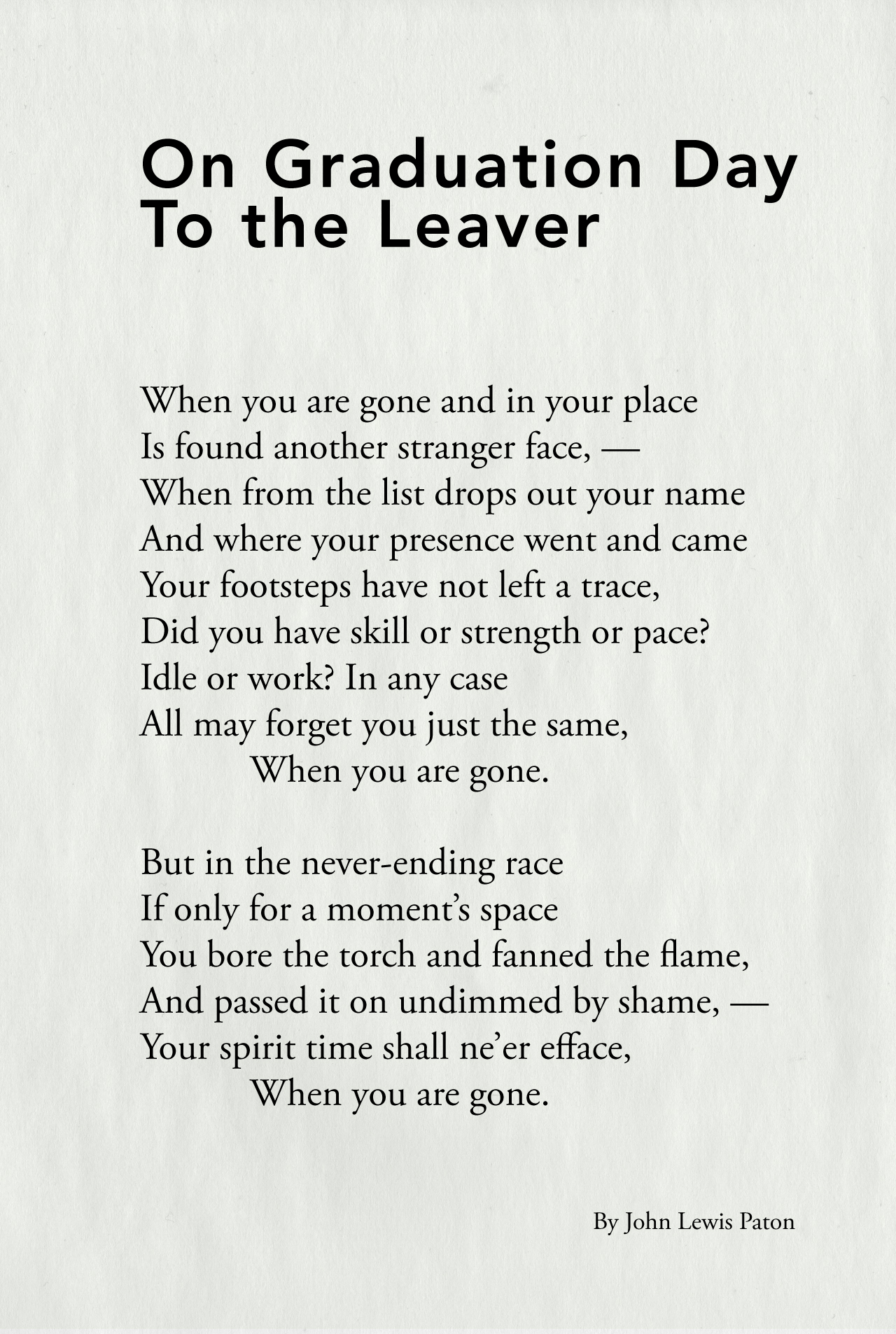

Before leaving Memorial, Mr. Paton wrote a poem called “To the Leaver.” It can be read as a poem for students preparing to graduate or as a reflection on his own time spent at the college.

In classic Paton fashion, the poem values one’s contribution to the life of the community over individual accomplishments that can fade from memory.

In 2005, one of the trees that Mr. Paton planted on the old Parade Street grounds was relocated to the campus on Elizabeth Avenue.

It still stands as a symbol of his contribution to our sense of purpose. A guiding spirit that remains with us and stands the test of time.