LAST WORD

By Dr. Kevin Major, B.Sc.’73, Honorary D.Litt.’11

For me, in the end, it is all about the faces. It is not the public pageantry, the precisely timed civic display of remembrance, as important as that is. It is the individual faces that implant themselves in my mind, the single soldier or nurse behind the vast, monumental event that was The Great War.

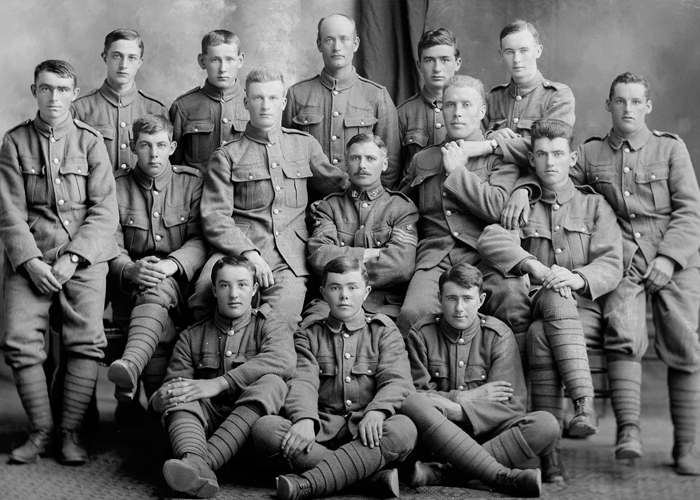

For me the most moving images of the Newfoundland Regiment in the war are not those of troops crowding the decks of the Florizel, or of soldiers marching through the cobbled streets of France, or even of weary men, hands clutching rifles, ready to clamber over the trench lip and into battle. It is rather the dozens of studio photographs taken of the platoons of young innocents, prior to being sent off and into the battlegrounds of Gallipoli and France. Some appear to have been taken later in the war at Garland Studio in St. John’s prior to embarkation for Europe, but the photographs I find most affecting were likely taken while the first recruits were in training in 1915, not long before Lord Kitchener’s announcement of the Regiment’s first assignment. “I am sending you to the Dardanelles!”

I believe these photographs make up some of the most profound portraits to ever come from this or any war. They are formal arrangements of a dozen or more Regiment men, in three rows — one standing, one seated on chairs or the arms of chairs, and a third row sitting cross-legged on the floor in front. The subjects are a mix of outport lads and corner boys, of merchant sons and cod fishermen, of store clerks and men who spent their days in the lumberwoods, of graduates of the dominion’s finest schools and men who couldn’t write their own names. The soldiers had obviously been told not to smile, to look their uniformed best for the folks back home. They showed their pride at having been fashioned into a hardened Newfoundland Regiment of fighting men.

They appear calm, as calm as their uncertain futures will allow. I detect a measure of apprehension in their eyes, a keenness tempered by having not yet been tested on the battlefield. I see the exuberance of youth held in check by the need to show their readiness for war. It would be just a few months to the time of their landing at Suvla Bay, and a year to their digging themselves into the trenches of the Somme. Their soldiers’ lives were all ahead of them. They had little notion of what to expect.

But what strikes me most of all is how they are just like faces we all know. Isn’t he the spit of that young fellow up the street? Didn’t he used to play football in Bannerman Park? Remember him from down the shore — by heavens, he was a strapping lad, he was. Each one of them looks like he could be a younger brother, a nephew . . . a son. My heart aches, as all our hearts do now, knowing that many of these men, in picture after picture, would not see the end of the war, would never find their way back across the sea to home. That we would come to know them as names on headstones and memorial plaques set into foreign soil.

It is sobering words we recite each July 1, each Nov. 11. We will remember them. Most surely we will, and think of them as the men they would have become had war not denied them the chance to live out their youth and to grow old, to have their photographs taken again and again.

Dr. Kevin Major is one of Canada’s most celebrated authors, and has enjoyed a successful writing career that has spanned almost four decades. His award-winning work ranges across genres and has been adapted for stage and screen. His 1995 book, No Man’s Land, is widely considered to be required reading on the topic of the Newfoundland Regiment at Beaumont-Hamel. The Regiment also plays a part in his newest novel, Found Far and Wide, a section of which is set on the battlegrounds of Gallipoli. Born and raised in Stephenville, N.L., he now resides in St. John’s.