Chapter 4: The Story – Dead Reckoning

St. Lawrence – 8 am

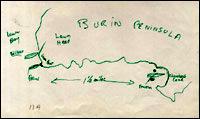

February 18 was Ash Wednesday and most St. Lawrence residents attended an early-morning church service before returning home or heading to work. The small mining town was located about three miles from Chambers Cove, where the Truxtun had gone aground, and about six miles from the Pollux at Lawn Point. As the townspeople went about their usual weekday routines, no one suspected that 389 men were fighting for survival in the familiar coves that lay just a few hours' walk away.

Iron Springs Mine was a major employer in the town and by 8:00 was already bustling with the activity of an early-morning shift. Outside the mine, three workers – Mike Turpin, Sylvester Edwards, and Tom Beck – were loading trucks with fluorspar when they suddenly saw a man stumbling toward them through the sleet and snow. It was Edward Bergeron of the Truxtun.

The miners took Bergeron inside one of the buildings and sat him down near a warm iron stove. Soon everyone at the mine knew about the grounded destroyer at Chambers Cove. The mine's assistant manager, Howard Farrell, shut down operations for the day so that all activity could be directed toward rescuing the shipwrecked sailors. Turpin, Edwards, and Beck immediately ran off in the direction of the cove, while other men gathered ropes, axes, blankets, food, and other supplies before also setting out toward the destroyer.

Before they left, the miners sent word to St. Lawrence that a ship was aground in Chambers Cove and that rescuers, sleds, and supplies were needed. The news spread quickly among the townspeople and it seemed that everyone was emptying their pantries and closets to donate all of their food, clothing, and blankets to the men of the Truxtun. Trucks brought supplies from the town to Iron Springs, where miners and townspeople kept pots of soup and kettles of water bubbling away on top of the stove in anticipation of the survivors' arrival.

Rescue, Part I – The Truxtun

Turpin, Edwards, and Beck were the first to arrive at the cove. When they looked over the edge of the cliff they saw a terrifying and heartbreaking scene – about 100 men were clinging to safety lines draped over the Truxtun's side, while a couple dozen more were in the water, desperately trying to hold onto wooden crates and other debris floating around the ship. Every now and then a wave ripped the debris from one man's grip or tossed another man toward the jagged rocks lining the coast. It was impossible to know how many had already died.

The three Newfoundlanders sprang into action. Turpin and Beck climbed down to the beach using the rope Bergeron had fastened to a knob of ice at the top of the cliff; Beck stayed above to hold onto the line. Once below, Turpin and Edwards waded hip-deep into the icy water and began hauling in some of the survivors nearest the coast. Soon, other St. Lawrence residents began to arrive. For hours these men tirelessly worked in the wind and sleet to rescue American sailors stranded off their shore. They waded into the icy waters and pushed through the oily muck; they lit fires on the rocky beach; and many also gave their own coats, socks, hats, and other clothes to the freezing, oil-soaked survivors. The Newfoundlanders saved many men that day, but they also saw many die. Some sailors drowned in the water and others were dashed against the rocks; a few made it to shore only to die moments later from exposure.

Those who lived were exhausted and often semi-conscious. They would not be able to climb over the cliff themselves, so the Newfoundlanders decided to tie ropes under the survivors' arms and pull them up. But there was a problem. The first two sailors brought up were bleeding and badly bruised by the time they reached the top – the men were simply too weak to push themselves away from the jagged rock face as they were hauled up the cliff. There was no alternative: the Newfoundland men would have to carry the survivors to the top of the cliff in order to get them to safety.

It was slow and backbreaking work. One by one, the men from St. Lawrence hoisted a survivor over their shoulders, held onto the rope, and painstakingly made their way up cliff. At the top, eight or nine men held onto the line to support the weight of the two men coming up. Complicating matters was the fuel oil encasing most of the survivors' bodies and adding about 50 pounds to their weight. Once at the top, the survivors were directed to Iron Springs Mine. If they took a shortcut inland, over the brush and through hip-deep snowdrifts, then the mine was about a 30-minute walk away. Some of the stronger men walked, while the Newfoundlanders took other survivors to the mine on their small horse-drawn sleds.

Iron Springs Mine, St. Lawrence

The survivors began to arrive at the mine, disoriented and exhausted. Many were semi-conscious and few seemed entirely aware of what was going on. The people at the mine were shocked by how much oil covered the sailors' frozen bodies. It became quickly apparent that they would need much more than hot soup, tea, and dry clothes. These men needed to be bathed in warm water if they were to survive, and as quickly as possible. Word was sent to the women of St. Lawrence to bring to Iron Springs their galvanized tubs, soap, and as much clothing, blankets, and food as they could spare. In the meantime, great quantities of soup, tea, and coffee were prepared in the mine house.

It did not take long for the women to arrive and begin their work. Semi-conscious survivors were laid out on tables and stripped of their oil-soaked clothes. The women filled their tubs with hot water and bathed every survivor that came into the mine house. They scrubbed the oil from their pores and the cold from their bones, gently rubbing life and feeling back into frozen limbs and numb bodies. Some men remained unconscious for the entire process, others awoke to find themselves naked and being bathed by strange women in a strange building. But it was so warm and everyone was so kind that many sailors sank back into semi-consciousness and surrendered themselves to the generous care of the townspeople. For hours oil-coated men straggled into Iron Springs, and for hours the women worked tirelessly.

Once the survivors were bathed, the women dressed them in dry clothes and fed them warm soup and hot tea. Everything the men ate and wore had come from homes belonging to these women and their neighbours – food from their cupboards, clothes from their closets, and blankets from their beds. Some rescuers even returned home from the wreck site to find that they had no clothes to change into – everything they owned had been given away to the men in the US Navy! After they were dressed and fed, the survivors were put into trucks and carried away to various homes in St. Lawrence, where families took them in and cared for them all night long.