What happened in Sailortown?

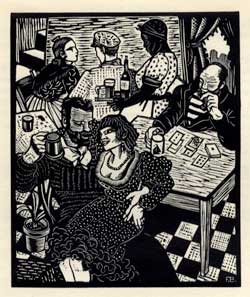

Sailortown was thought to be a place full of vices. There, extreme poverty bred crime and prostitution, with drink, sex and drugs charging the atmosphere with even more tension. However, the most notorious part of what went on in sailortown was called crimping. This was a complicated business. There were great variations between crimps—the people who controlled the crimping network—depending on the size of their operation, their aggressiveness and the level of competition in their port. Crimps essentially took control of seafarers' wages and provided them with lodging and entertainment, like an agent. Boarding-house keepers, men and women who were already providers of a seafarer's accommodations, were often also crimps and either had connections with the community where the seafarer could go have a bite to eat or to drink, go to a show, or to hire a prostitute, or the boarding house had all these amenities in house. Once the client's wages ran out, they were in debt to the crimp, who would find them their next ship and take their advance wages as repayment (Fingard 1982).

Getting seafarers onto ships, however, was not always easy. Most crimps and boarding-house owners would begin to hint that the seafarer was in debt by changing their attitudes during his stay.

They were very nice to you while you were homeward bound ... while you had money yet; you'd just come in and had been paid off. But as soon as ever you're outward bound—outward bound means when your money is out and the two weeks' board you had paid was up—well then, it was nothing but black faces after that. While you're homeward bound it was ham and eggs regularly and plenty of them; now it was, "What will you have for your breakfast—an egg or a herring?" (Barnes 1931, 307).

Generally seafarers were aware of their debt and would take the ship arranged for them by their boarding-house keeper, handing them their advance to cover the money owed. However, sometimes seafarers were not willing to go or the crimps were not as patient. In these cases, the crimp would get the seafarer to sign the ship's articles while under the influence of alcohol or drugs and then deposit the unfortunate and unconscious seafarer in the foc's'le. This was called 'Shanghaiing' and stories about these acts grew ever more exaggerated until it was claimed that crimps or would-be crimps were kidnapping, drugging and shipping seafarers out of bars, brothels and alleys by the dozens. The most oft repeated story of all was that of shanghaiing a dead body. In New Orleans,

However, sometimes seafarers were not willing to go or the crimps were not as patient. In these cases, the crimp would get the seafarer to sign the ship's articles while under the influence of alcohol or drugs and then deposit the unfortunate and unconscious seafarer in the foc's'le. This was called 'Shanghaiing' and stories about these acts grew ever more exaggerated until it was claimed that crimps or would-be crimps were kidnapping, drugging and shipping seafarers out of bars, brothels and alleys by the dozens. The most oft repeated story of all was that of shanghaiing a dead body. In New Orleans,

a story is told about one of these crimps shipping a corpse—dressed in a monkey-jacket and canvas trousers—taken from an undertakers. When the second mate tried to rouse it and found he couldn't, he dragged it up on deck, stood it against the capstan, telling it to 'keep a good look out'. When it failed to report a light he bashed the hell out of it (Hugill 1967, 184).

Such a story existed in every seaport, from London to Quebec, but it is unlikely that shanghaiing ever reached these extremes.

Why was crimping done?

Shanghaiing and crimping, to outsiders of sailortown and the seafaring world, seems like extortion and kidnapping. Why would seafarers give their wages to a stranger? Crimping could be mutually beneficial to sailors and crimps. Crimps provided direction to men who did not know the local area by giving them a place to stay, food, and providing the entertainment that many men were looking to enjoy. Crimps also managed the availability of seafaring labour. They could withhold and supply men and influence the wages being offered, especially in foreign ports. It was in both the crimps and the seafarer's interest that wages were higher. But the question remains: If crimping helped sailors get the services they wanted, then why did people write about how bad it was for them?