A Sailor's Kit

"I got an old wooden sailor's chest belonging to my mother's brother, Captain Charles Allen, and I spent my time until the ship was ready, packing my clothes in the chest and getting everything ready. They had to get me a pair of sea boots, oilcoat and pants, a blue knitted sailor's Guernsey, canvas jumper, a belt and sheath and knife. Then I was proud as a peacock ..."

–William Morris Barnes, 1930

"The carpenter, old Mr. Jerry Smith, was given the commission to make my little blue sea-chest. As no member of the family had ever been to sea, the old folks were somewhat at a loss as to what I would require, but this was got over by pressing into service old Captain Edmund Bray, a retired shipmaster, who readily entered into the family councils, and, acting on his suggestions, my outfit was soon completed and packed away in my chest."

–John D. Whidden, 1908

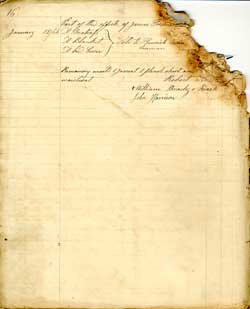

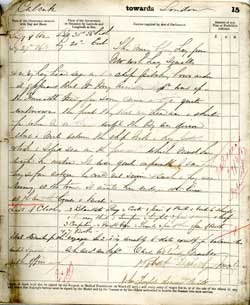

When William Morris Barnes and John D. Whidden went to sea an important part of their time before embarking was spent on preparing their sea-chests, filling them with clothing and other things they (or retired shipmasters) deemed necessary for work at sea. Barnes gives us a hint of what might have gone into a Boy's sea-chest, such as oil clothes and a sailor's Guernsey. Barnes was from a merchant family in St. John's and thus would have been able to afford a more specialized kit. Neither of the apprentices James Foster, of the Tangier (42191, 1864) or William Henry Armstrong, of the Sir Henry Lawrence (51496, 1867) had oil clothes in their inventories when they died, and only Armstrong owned a jumper, which was similar to a Guernsey. Foster owned only six items and had no other pair of pants than those he drowned in. Armstrong, on the other hand, had about 22 items. Both young men owned the basic sailor's kit, though Foster's was by far more basic than Armstrong's.

|

|

| James Foster Apprentice |

William H. Armstrong Apprentice |

|

| Bag | 1 | |

| Bed | 1 | |

| Bed Cover | 1 | |

| Blanket | 1 | 1 |

| Ditty Box | 1 | |

| Cap | 1 | |

| Chest | 1 | |

| Coat | 1 | |

| Collar | 1 | |

| Jacket | 1 | |

| Jumper | 1 | |

| Mattress | 1 | |

| Millboy1 | 1 | |

| Pants | 4 | |

| Flannel Shirt | 1 | |

| White Shirt | 1 | |

| Shirt | 5 | |

| Shoes | 1 | |

| Vest | 1 | |

| Waistcoat | 1 |

1 Item Unknown

From these two inventories it can be surmised that the basic sailor's possessions where not much different from what a landward working-man would own. Besides pants (which he was likely wearing at death) Foster owns all the components to a three-piece suit of clothes, a common form of dress for men in the nineteenth-century. This comprised of a jacket or coat, a vest or waistcoat and pants. Very little in these inventories are things specific to the sailoring profession.

Capacity

James Foster and William Armstrong were apprentices, however, and they cannot represent the entire range of possessions of the crew. Crewmembers from across various capacities died aboard ships and, except for men like Frederick Brown, they would have owned more things than the two apprentices.

Aboard a sailing ship, the rate of pay was divided into a hierarchy based on type of labour. There were ordinary and able-bodied seamen who were on the bottom of the pay scale, with masters and officers at the top. In the middle were tradesmen like carpenters, cooks and stewards. It has been suggested that these men were not only differentiated in terms of work, but also in terms of where they lived on board a vessel (Creighton 1995, 31). Seamen lived in the forecastle, tradesmen were in steerage or the middle of the vessel, and finally the officers had their berths aft. This is significant because where a crewmember slept dictated the amount of space he had to bring possessions with him (see Space Requirements) and this, coupled with wage rates, determined how much a sailor could own. In the sample of recovered inventories, a man who lived in the forecastle owned, on average, about 25 items. An officer owned on average 157 items or six times the amount of things as an able-bodied seaman. Both groups owned items from the basic kit, which included:

- Cloth Bags

- Blankets

- Body Flannels (full body underwear)

- Books

- Boots

- Braces

- Caps

- Coat

- Collar

- Comforter

- Drawers

- Pocket Handkerchiefs

- Muffler (Man's Scarf)

- Neckties

- Pants

- Pillow

- Pillow Cases

- Sheets

- Flannel Shirts

- Linen Shirts

- White Shirts

- Shirts

- Shoes & Boots

- Singlets (underwear)

- Stockings

- Towels

- Trousers

- White Trousers

- Woolen Trousers

- Vests

- Waistcoats

Officers were more likely to own items designated as better quality. These might be linen shirts, or other bleached white items, that would have been more expensive to keep clean. They did not tend to own cheaper fabrics like flannel (Reeves 1980, 64-5). Both groups of men owned books, though the officers had considerably more than sailors. Their reading material was often identified: for example, Bibles and prayer books were often listed in inventories. Officers also owned more bedding such as sheets, pillows and pillow cases, but did not appear to commonly own beds. This may be because the term 'bed' referred to a tick, or a large fabric case which held straw. Sailors carried their 'beds' from ship to ship, but a bed might have been provided for the officers, especially if they had sailed with the same ship for many voyages. For seamen, sheets and pillows were considered a luxury (Whidden 1908, 8) but beds, mattresses, hammocks and bed rugs were common.

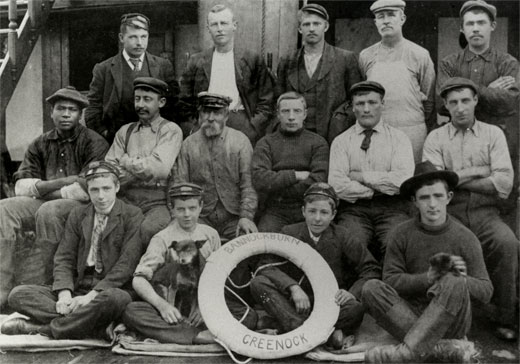

Bannockburn

Photographs are very important resources for understanding clothing. This picture is of a sailing vessel called the Bannockburn (Official Number 93183, 1891). This ship was registered in Greenock and it worked in the home trade and was also foreign-going. The Bannockburn's home trade crew agreement from 1891 states that they carried fifteen crew members, which is the number of men in the picture.

This photograph illustrates what the clothing of James Foster and William Armstrong might have looked like, as well as other items in the basic kit.

Caps

The men of the Bannockburn, with only two exceptions, all have their heads covered. Of these hats, the most popular selection was the cap. In the photo, there are six caps, with pilot hats also being numerous. William Armstrong owned one cap, but both may have been wearing a hat when they fell overboard. Few men would have gone without a hat in the nineteenth-century (Severa 1995, 357). Of 25 inventories taken, 14 men left 28 caps. It is impossible to know what the inventory-taker meant by "cap," except that is a type of hat. An examination of many inventories suggests the breadth of terminology that existed for different articles of clothing in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century. In the 25 inventories used in the research which has informed this website, there are 28 caps, 2 night caps, 2 scotch caps, 1 hat, 1 black hat, 2 felt hats, 1 panama hat, and 6 "caps & hats," bringing the total headgear to 43 items.

Coats and Jackets

Like the ambiguity between caps and hats, coats and jackets could mean a different cut or simply that the inventory-taker chose a certain word. The difference between coats and jackets is negligible until another term is attached to the garments, like pea jacket or reefer jacket, as compared to a frock coat. The boy in the picture is wearing a pea jacket, probably made out of wool. There are five coats in the picture, but the other men probably owned their own as well. Both Foster and Armstrong had, respectively, a jacket and a coat.

Jumpers and Guernseys

Armstrong had a jumper in his inventory. This is a word for sweater which has fallen by the wayside in North America, but is still current in Britain. The man in the picture is wearing a lovely knit jumper with ribbing down the front and the sleeves and around the neck and cuffs. There is one other jumper in the picture, of a similar style, but without the ribbing. In the 25 inventories, there were 17 jumpers, Guernseys or sweaters owned between nine men. One of the items the autobiographer Captain Barnes remembered taking to sea with him as a child was a sailor's Guernsey. These were knitted sweaters named after the British Channel Island.

Pants

Pants or trousers were essential parts of a man's dress in the nineteenth-century. Before the 1830s, however, they were optional dress, being exchangeable with breeches. Trousers are particularly interesting when discussing sailors, however, because during the eighteenth and early nineteenth-century sailors were the most visible wearers of trousers (Styles 2007, 197). In the early nineteenth-century, pants were done up using a panel or font-fall fly that was buttoned. These pants, and most in trousers, have what we would consider modern flies, or the split-fall. These pants were closed using buttons, as zippers were not invented until the 1890s and were not used in clothing until the 1930s (see the man in the middle row, third from the left). Pants were made from a variety of fabrics, some in the inventories include canvas and duck (which were similar), flannel, wool, and, as indicated by the name dungarees, denim.

Shirts

This young boy is wearing a collar-less shirt. It was called a Crimean shirt in the inventories. Like pants, shirts are frequently distinguished by their fabric and also their colour. The inventories list blue flannel shirts, coloured shirts, linen shirts, serge shirts, wool shirts and white shirts. White shirts were expensive to own because they had to be cleaned more frequently. Collars were especially difficult to keep clean and they were often purchased separately from the shirt. This boy was probably too young to own such collars, but they did appear in significant numbers in the inventories.

Footwear

Every member of the crew would have owned some sort of footwear. In the Bannockburn photograph, there are both boots and shoes. A pair of rubber boots is shown to the left. In the inventories there were three pairs of India rubber boots, which would have been useful for keeping feet dry but would have been slippery and cold in freezing winter conditions. Very few able-bodied seamen owned more than one pair of shoes. Only officers, stewards and masters appeared to own more than one pair or type of footwear.

Waistcoats

Completing the three-piece suit of clothes was the waistcoat. This article of clothing would go over the shirt and the braces. In the photograph of the Bannockburn, there are two men wearing waistcoats, one with lapels (as on the left) and one without. Men's dress was quite varied in the nineteenth-century, with different styles of collars and lapels, and the length and fit of coats and waistcoats constantly changing. Though the basic format of the suit of clothes, with pants and a combination of waistcoat, shirt and coat, stayed relatively constant, their decoration and construction were in continuous flux. James Forster was in possession of a waistcoat.

Braces

These were important items for keeping up a man's pants. Belts were another option, but they rarely appeared in inventories. Braces were also rare inventories for Able Bodied Seamen, but they probably died, or were buried, wearing their only pair. Only a very poor man would use replace braces or his belt with rope. The braces went over the shirt and under the waistcoat. On the Bannockburn, two men are wearing braces, though the second pair are mostly hidden by the man's coat.

Collars

In the picture of the Bannockburn, the collars most men were wearing were attached to their shirts, as part of the garment. However, in the nineteenth-century, collars were also made to be separate from the shirt, so that they could be easily cleaned and, for the most fashionable wear, starched to stiffness. Of the men in the picture, it appears that only the master (top, first man on the left) could have been wearing a detachable collar in the photo. He would be pleased to know, however, that it is impossible to tell the difference. Officers carried on average 13 collars, whereas only one Able-Bodied seaman in the sample owned a collar.

Neckties

While neckties, like collars, would seem to be owned primarily by the officers of the crew, about a third of able-bodied seamen owned them and in significant quantities. The master of the Bannockburn to the left is sporting a lovely tie with white spots. In the image there is a solid-colour tie and also a striped one. The striped tie is quite askew, as though the young man were rushed into the picture. The fellow with the solid tie has his tucked into his shirt.

There were many things in the basic kit which do not appear in the Bannockburn photograph. Bags, handkerchiefs, mufflers, towels were common items not in the picture. Undergarments are hopefully there but not visible, which include drawers, singlets, body flannels, stockings and vests.

Surprises

Occasionally odd things turn up in inventories. Items from foreign countries, large quantities of food, specialized instruments, specific brand-named items, jewelry and other personal items, and furniture.

Foreign

- Chinese Work Box

- Chinese Soap Stone Ornaments

Brands

- Minilla-Cheroits Cigarettes

- Brooks & Co. Tea

Food

- 54 Sides of Bacon

- 154lb Cheese

- 385lb Ham

Instruments

- Flute

- Forceps

- Looking Glass

- Water Can

Jewelry

- Bracelets

- a Ring

Furniture

- Mosquito Curtain

- Wash Stand

- Writing Desk

- Chest of Drawers

- Inkstand

Personal Items

- Tooth Brushes

- Slippers

- Wash Stand Fixtures

- Photographs

- a Miniature

- a Passport

The owners of these items were generally either officers or the stewards of large passenger ships, who would have had significantly better wages than the average able-bodied seaman. Able-bodied seamen, however, were the owners of the miniature, the passport, one of six looking glasses (mirrors) and the bracelets. The bracelets, and the Chinese box and ornaments were probably either souvenirs or items of curiosity purchased for resale in Britain. Similarly, in 1934, AB Alfred Etherington owned 27 silk handkerchiefs when he died on a run between Europe, Vladivostok, USSR, and Yokohama, Japan, which were probably either gifts or meant for resale. The large quantity of food owned by the Steward James Reeves also may have been destined for sale.

Sentimental items such as letters, miniatures, and photographs would not, to us, be out of place but they were relatively rare in inventories. Furniture, on the other hand, seems odd, but officers, masters, and stewards were the owners of these things, and they had the room in their quarters to accommodate large objects like a chest of drawers. The flute suggests that Thomas Howard, steward, had enough leisure time to play music. The forceps were owned by the other steward, James Reeves, and could have been birthing forceps or dental forceps for pulling teeth. The watering can indicates that Reeves also may have been caring for plants or using it as a bathing aid.