Cowboys of the Sea:

Cattlemen aboard Merchant Vessels

Cattlemen unsettle our notions of "seamen." They were a large group of transient workers who took care of the cattle on board merchant shipping vessels. Sometimes they are referred to as "stockmen" but "cattlemen" is more common. They appear in the Crew Agreements of the home trade from the 1830s when steamships "opened the entire urban market for food of the west coast of England and Scotland" (Perren, 51). Stewards and cooks looked after cattle on board until, in the 1870s, steamship development made a transatlantic trade possible to satisfy a growing demand in urban centres and the scale of the trade changed entirely. Like other categories of "strangers," cattlemen were paid 1s per-month. Perhaps they received payments from other sources, but it is conceivable they worked only for the cost of their shipboard food and lodgings. The transportation of livestock by sea trade has happened for a very long time. Sailing ships could not carry large numbers of cattle, and even with the early steamships, in the 1830s and 40s, the trade was limited to short distances(51). As larger metal built hulls and powerful marine engines drastically cut travel times, and allowed for some improvement in the quality of livestock quarters, the North Atlantic cattle trade grew steadily. By the turn of the century, the United States was the origin of over 70% of Britain's imported cattle (52).

Cattle were carried across the Atlantic in a variety of vessels: custom built liners, regular passenger liners, as well as hastily modified tramp steamers where accommodations were temporary and conditions for animals and men often deplorable. Without sufficient fodder and attendants to care for the livestock, there were incidents of hundreds of sickened and malnourished cattle being disposed of at sea. Sometimes cattle were washed overboard in severe storms. Historian Richard Perren points out that, in response to public outcry and lobbying, after 1880 cattle were supposed to be carried between decks and provided with constant attention(53).

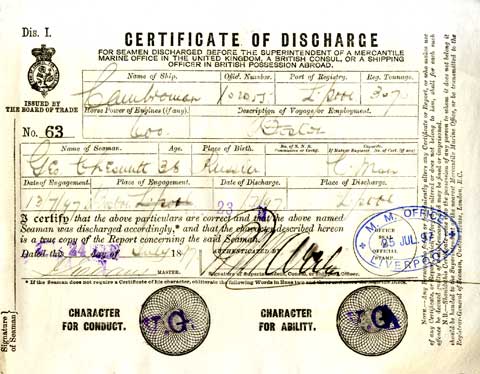

The image on this page shows the deck of the Federal Steam Navigation Company's Cornwall in 1901 when it was en route from New Zealand to deliver horses to British troops then fighting in the Boer War. The Cornwall's Crew Agreement, retrieved from the MHA (Official No 105897 1902), shows scores of men taken on in Wellington as grooms. The understanding was that they would be paid one shilling a month until "discharged at a port in South Africa when [the] horses are all landed". After a voyage lasting six weeks, they quit the ship in Port Natal and the master made use of the convenience of recording them as deserters so that the formalities of issuing each of them a discharge certificate could be avoided.  A different practice in the case of the cattle-ship Cambroman (Official No 102055, 1897, MHA) meant that scores of discharge certificates were prepared, but these were never collected by the cattlemen for whom they were made out. Uncollected, they went with the Agreement to the office of the RGSS. Leafing through these sheaves of documents the heterogeneity of these men impresses the researcher: they came from Russia and India amongst many other places. Their reasons for working as cattlemen, or as grooms in the case of the Cornwall, were likely equally mixed, but emigration either temporarily or permanently could reasonably be thought a motive for some. Rarely could these men provide permanent addresses to be filled in on the Agreement.

A different practice in the case of the cattle-ship Cambroman (Official No 102055, 1897, MHA) meant that scores of discharge certificates were prepared, but these were never collected by the cattlemen for whom they were made out. Uncollected, they went with the Agreement to the office of the RGSS. Leafing through these sheaves of documents the heterogeneity of these men impresses the researcher: they came from Russia and India amongst many other places. Their reasons for working as cattlemen, or as grooms in the case of the Cornwall, were likely equally mixed, but emigration either temporarily or permanently could reasonably be thought a motive for some. Rarely could these men provide permanent addresses to be filled in on the Agreement.