|

OF SERVICES TO CHILDREN AND YOUTH: POLICY RE/VISIONS IN NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR Rosonna Tite

This paper focuses on the implementation of a new model of service coordination for children and youth in Newfoundland and Labrador (Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, 1997). The model, which draws together the services of the Departments of Education, Health, Social Services and Justice, is based on an "Integrated Services Management Approach" aimed at providing specific supports or interventions for children with special needs. For the purpose of the policy a child with a special need is defined as "one who is identified to be at risk or has a special need as determined by one or more of the service partners" (Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, 1996: 1). My interest in this most recent initiative has to do with my ongoing research into the relationship between teachers' work and the school's response to victims of child abuse. The school's role in responding to child abuse has been generally

viewed in two ways: surveillance and prevention. The surveillance

role involves requiring teachers to report disclosures or suspicions of

abuse to their local Child Protection Service (Government of Newfoundland

and Labrador, 1993). This is a legal requirement and therefore highly

emphasized by school boards. Prevention efforts, such as the development

of curriculum materials or workshops for teachers, have so far been given

less attention (Tite, 1993, 1994, 1996). My goal in this paper is

to focus on the integrated services approach in order (1) to explore its

potential with regard to improving current surveillance and prevention

models and (2) to speculate on the extent to which the new policy reflects

an adequate response to the difficulties associated with teachers' surveillance

role.

The Coordination of Services The current trend toward the coordination of services is based on the idea that "coordinated intervention is the ideal goal...and that a collaborative multi-disciplinary response is needed "...to increase reporting and conviction rates, increase the effectiveness of treatment, and to decrease the trauma of disclosure for survivors" (Kinnon, 1998, 8). Clearly, though, while the formal coordination of services has influenced the thinking and activity of the professionals involved (Frenken & Van Stolk, 1990; Furniss, 1991; Martin, 1992; McGuire & Grant, 1991; Trute et al, 1992), and although a range of collaborative models have been developed (Hunter, Yuille, & Harvey, 1990; Kilker, 1989; Rogers, 1990), current intervention in Canada and throughout the USA remains fragmented and ineffective (Cotter & Kuehnelle, 1991; Trute et al, 1992). In general, the difficulties are attributed to philosophical disagreements that divide professional communities in their attitudes toward victims and offenders and their beliefs about the causes and consequences of abuse (Finkelhor & Strapko, 1992; Trute et al, 1992; Kays, 1990). As teachers have become increasingly persuaded to take part in

coordinated intervention, much of the research on the school's role has

been aimed at uncovering the procedural difficulties associated with reporting

cases to Child Protection Services (CPS) (Brosig & Kalichman, 1992;

Foster, 1991; McEvoy, 1990). Teachers' lack of knowledge about abuse

(Abrahams, Casey & Daro, 1992; Baxter & Beer, 1990; Beck, Ogloff

& Corbishley, 1994), their general wariness about becoming involved,

and the conflicts that arise in dealing with agents from outside of the

school (Haase & Kempe, 1990; Zellman & Antler, 1990; Zellman, 1990)

have also been emphasised. What is often missing from this work is

a full understanding of the overlapping bureaucratic, professional and

personal contexts in which identification and reporting decisions are made.

The Teacher's Role By focussing most of my previous research (in Ontario and Newfoundland) on teachers and their experiences and perspectives of both hypothetical and real cases, I have tried to develop our understanding of these contexts in several ways. These findings, drawn from Tite, 1993, 1994a, 1994b, 1994c. 1996, 1997; 1998 (forthcoming) and Tite & Hicks (1998) are summarized in general terms below: 1. Discrepancies between teachers' attitudes and the legal definitions/ requirements: Teachers seem reluctant to be bound by legal definitions or formal reporting requirements. Instead, they include a wide range of behaviours in their own theoretical definitions and often prefer to deal with cases informally at the school level. Underlying these informal interventions is the sense that some cases can be handled more effectively by the school than by CPS, a perception which seems rooted in a view of children which emphasises discipline and intellectual and emotional needs.2. Barriers to detection: The vast majority of teachers in both provinces indicated that they probably would not notice the signs of abuse if the child is not having trouble at school. It is clear, however, that classrooms present other complicating conditions. Detecting abuse is difficult, for example, in a setting where children frequently present themselves with minor injuries, where abused children can explain away injuries with excuses that sound entirely plausible in their familiarity, where it is not unusual to see a child who seems emotionally distressed, and where, increasingly, children are displaying advanced sexual knowledge and behaviour.3. Inadequate training: While interpreting children's symptoms in such circumstances would seem to require a sophisticated knowledge base, more than half of those surveyed in both provinces were unable to indicate whether their school board has a reporting policy, and fewer than half had attended a mandatory child abuse in-service session in the last five years.4. Difficulty of distinguishing between suspicion and proof: Many teachers engage in their own informal investigations of their suspicions, sometimes feeling that they need "proof" before making a formal report, but more often out of their professional concern for the "whole child" and maintaining good "working partnerships" between the home and school. This process is fraught with difficulty, however, as teachers often find themselves acting in ways that contradict their normal concerns for children's trust, privacy, and safety.5. Uncertainty/lack of consensus: Teachers indicate a pervasive sense of self-doubt about their role in the coordination of services. In part, this seems to arise out of the increased demand to be more responsive to abused children, and a lack of confidence in their ability to do so. For some, the uncertainty seems rooted in the perception that they are taking on a role which is outside of their normal teaching role. For others, it is a question of parents' intentions. Also evident is a lack of consensus about how to balance their concerns for children's safety against the need to maintain the child's family unit, especially where there is a question about CPS ability to provide long-term solutions.6. Conflicting views about the victims of abuse: Related to this are the findings from my most recent research which suggest significant differences in teachers' and social workers' views about the victims of child sexual abuse i.e., their opinions about the characteristics and credibility of sexual abuse victims and the extent to which they attribute to the victim some responsibility for the abuse. The most obvious issue is the extent to which the child's age and behaviour appears differentially to influence attitudes about the child's credibility, with teachers more likely than social workers to accord little credibility to adolescent victims, particularly if they are seen as a "problem" children (e.g., promiscuous or runaways).7. Frustration about the outcome of reports to CPS: Teachers' frustration with the outcomes of their reports is very clear. There is widespread concern about "budget cuts, long waiting periods and huge caseloads," and an overriding sense that CPS is simply unable to cope. Another source of frustration concerns disagreements about the severity of the abuse, particularly with cases of emotional abuse and neglect. Teachers often feel unheard or misunderstood by child protection workers when they believe that they have clear ongoing evidence of abuse or neglect, but where there are no "marks" or "witnesses" to support them.8. Concerns about consequences: Related to this is teachers' fear that reporting will only make matters worse. This is expressed in a variety of ways: as apprehension about traumatizing the child at the early stages of disclosure; as a concern about upsetting the other children in the class; as fear that parents may react to the report by becoming even more abusive; and as anxiety about the difficulties of dealing with the child and his/ her parents after a report. It is clear as well that some teachers see themselves at risk of personal revenge, either in the form of physical violence or attacks on their professional credibility.9. Significant gender differences: While I was unable to conduct a gender analysis for the Ontario study, the findings from Newfoundland and Labrador indicate statistically significant gender differences in the identification of cases; 42.7% of men teachers compared to 60.1% of women teachers indicated that they had suspected a case of abuse. There are two interesting aspects to this gender distinction, the first the fact that men tend to predominate in the higher grades and administrative roles, the second pertaining to policy and training. The prevailing view is that identification should be influenced by type of teaching assignment and exposure to policy and training. However, the data here is very clear: only women's suspicion rates are not statistically influenced by grade level or type of class assignment, and only for women is there a strong positive correlation between suspicion and in-service training and between suspicion and awareness of policy. Put another way, after controlling for grade level, type of class assignment, and exposure to policy and training, differences in suspicion rates remained significant for males, but not for females.10. The potential for inappropriate screening: The majority of teachers are reluctant to make formal reports to CPS, but most of their suspicions are reported, and most reporting is done through the principal. Principals seem adequately prepared to handle reports, but at least half seem unwilling to pass teachers' reports on to CPS, or to encourage the teachers to do so. Apart from the possible effect of gender, this seems connected to how abuse is narrowly defined procedurally and to principals' experiences of what CPS will investigate and what they will otherwise dismiss. Thus, although teachers' reporting seems initially to be consistent with accepted procedures, in practice the process appears to be sufficiently vulnerable to principals' responsiveness to raise questions about the potential for the inappropriate screening of cases at the school level.

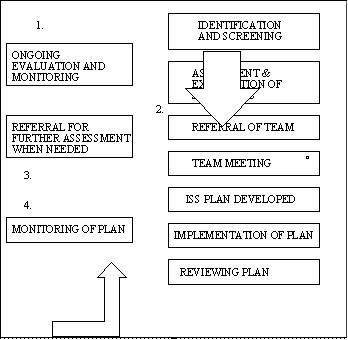

Because they so clearly underline the educational difficulties associated with reporting, these findings compel us to consider the potential benefits (or drawbacks) of an integrated services management approach. The most obvious question seems to be whether the model provides an opportunity for teachers to become more engaged in the problem of child abuse, while resolving their own difficulties within the educational context, and coordinating their activity with other professionals such as social workers, health-care providers and justice officials. In Newfoundland and Labrador, the Integrated Services Management Approach is meant to be a collaborative process involving the child, the parents, and service providers from Education, Health, and Social Services. The idea is that personnel from the relevant agencies work together to identify the child's needs, to define appropriate goals for meeting those needs, and to provide the required supports and services. The aim is to provide a holistic approach which ensures that the child and family are full partners in the process, while encouraging the sharing of knowledge and expertise among service providers. Although this paper is focussed on child abuse, it is important to note that this is not the only issue addressed by the model. In fact, it is designed to deal with a wide range of special needs and problems, e.g., hearing impairments, the need for a wheelchair, death or disability of the child's parents, learning disabilities, behavioural problems, shoplifting convictions, and so on. A central component of the Integrated Services Management Approach is The Individual Support Services Plan (ISSP). Given the objectives outlined above, presumably there is room within the ISSP planning process for flexibility in terms of the level of formality and format. Nevertheless, a formal process is outlined very clearly in the policy (see figure 1). As Figure 1 indicates, the process consists of four essential stages: pre-referral; referral; planning and implementation of the service plan. (i) The pre-referral stage: The ISSP process begins with screening and identification. Screening and identification is followed by assessment and exploration of strategies, and then, if a referral is not deemed necessary, the "service provider" should engage in ongoing evaluation and monitoring. Unfortunately, as we have seen, in terms of the child abuse issue, this is where the teachers' role generally begins and too often ends. This is because most of the difficulties associated with reporting, discussed above, act as barriers to the referral stage. To repeat: it is difficult to detect the symptoms of abuse in the classroom; too few teachers are aware of the legal definitions, school policies and legal reporting requirements; those who are aware often disagree with, or at least feel highly uncertain about the legal definitions and the official CPS response. Finally, given the significant gender differences along with the fact that the vast majority of school administrators are male, clearly, the chances of teachers' suspicions going beyond the pre-referral loop are low.  (ii) The referral stage: The second stage of the ISSP process is the referral stage. Prior to the implementation of the new integrated services management approach, a child abuse referral generally meant a quick phone call to CPS or the police (very few teachers in my samples indicated putting anything in writing). The ISSP process is different; here the key player is the Individual Support Services (ISS) Manager. A referral to an ISS Manager begins a process whereby he or she determines the membership of a team and completes a profile which is sent to the Child Services Coordinator and communicated to a Regional Services Management Team. In determining the composition of the ISSP team, the ISS Manager is expected to take into account the nature and complexity of the child's needs. Most teams, however, are expected to be comprised of the child, the parents/guardians, service providers, and other relevant players. (Government of Newfoundland, 1997, 8-12).

Close to one-half of the teachers in both my samples indicated that they never heard about the outcomes of their referrals. When I raised this issue at a recent ISSP workshop, I was told that this was "confidential" and therefore could not be communicated to teachers, leaving me to puzzle out how teachers could be "relevant players" or "service providers" without appropriate information. Since health, social services and justice officials can readily obtain children's school records, while teachers cannot have access to the outcomes of their referrals, we clearly need to question the extent to which the integrated service management approach is truly integrated or service oriented. (iii) The planning stage: The planning stage begins with a team meeting, a meeting which is seen as "a continuation of the problem solving process begun at the pre-referral stage" (23). The team meeting is meant to be: "child-focussed; a forum for shared decision-making; a means to acquire solutions to problems; a place for respectful honesty; inviting and comfortable for all members; a place where everyone's expertise and point of view is valued; and positive and optimistic about the child's future" (24). More specifically, the team is expected to develop an action plan. The plan is to consist of a set of prioritized goals for the child, a list of supports, services and recommendations for each goal, and a list of service personnel or agencies to be responsible for implementing the various components of the plan. The planning process is intended to be consensual, with team members reaching agreement on strategies, approaches and interventions, and ways of avoiding duplication of services.

(iv) Implementation of the service plan: After the meeting, individual team members with responsibility for implementing the ISSP are expected to engage in a number of tasks, the first of which is to complete the necessary paperwork. According to the document, this formalizes each team member's action plan and ensures that the identified objectives are met. Interestingly, teachers are mentioned in this section of the document which recommends, for example, that "School board office personnel, usually the special education teacher [author's emphasis] and relevant classroom/subject teacher(s), get together to complete the teaching portion of the ISSP ..." (26). While the document is unclear about teachers' role in cases where they are not official members of the team, it does indicate that if the ISSP includes an area for which additional expertise is necessary, the team members, in writing up the ISSP, should "include the relevant person" or recommend "resource materials to help write this portion of the ISSP" (27). Thus, presumably, teachers could be called upon at this point to become service providers. However, this is not made clear in the document, nor is there any mention of how this might work in cases of child abuse.Following the development of the ISSP, the team is expected to meet again to draw up a schedule for the interventions, and, once implemented, to meet again twice annually to review and monitor the child's progress. Interestingly, teachers are mentioned as a special case in this section of the document in reference to the scheduling of meetings, for it is noted that "a convenient arrangement for some schools is to schedule meetings to coincide with the normal parent-teacher interviews avoiding the need for parental travel to multiple meetings" (29). This is a puzzling statement, especially coming near the end of the document. Nowhere else is it suggested that teachers could play such a key role. In this paper I have considered the Integrated Services Management Approach only from the perspective of teachers' role in responding to child abuse. Further analysis of the model should include the perspectives of other professionals as well as other difficulties e.g., health issues, related to children "at risk." Nevertheless, this preliminary work holds particular significance for teachers and researchers concerned about the problem of child abuse. Specifically, teachers need to recognize the features of the new model which may act as systemic barriers to responding to abused children, and to begin questioning aspects of the new policy which do not seem to work well for them or the children they are trying to protect. At the same time, researchers need to be concerned with how policy revisions which appear to be neutral (on paper) may serve (in practice) to screen out cases in ways that reinforce the old idea that child abuse is a marginal social problem. REFERENCES Abrahams, N., Casey, K. & Daro, D. (1992). Teachers' knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about child abuse and its prevention, Child Abuse and Neglect, 16, 229-238. Baxter, G. & Beer, J. (1990). Educational needs of school personnel regarding child abuse and/or neglect. Psychological Reports, 67, 75-80. Beck, K., Ogloff, J. & Corbishley, A. (1994). Knowledge, compliance, and attitudes of teachers toward mandatory child abuse reporting in British Columbia. Canadian Journal of Education, 19 (1), 15-29. Brosig, C.L. & Kalichman, S.C. (1992). Child abuse reporting decisions: Effects of statutory wording of reporting requirements. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 23, 486-492. Cotter, L., & Kuehnle, K. (1991). Sexual abuse within the family. In S.A. Garcia and R. Batey (Eds.), Current perspectives in psychological, legal and ethical issues: Vol. 1A: Children and families: Abuse and endangerment. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. Finkelhor, D. & Strapko, (1992). Sexual abuse prevention education: A review of evaluation studies. In Willis, Holden, & Rosenberg (Eds.). Prevention of child maltreatment: Developmental and ecological perspectives. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Foster, W. (1991). Child abuse in schools: The statutory and common law obligations of educators. Education and Law Journal, 4, 1, 1-59. Frenken, J., & Van Stolk, B. (1990). Incest victims: Inadequate help by professionals. Child Abuse & Neglect, 14, 253-263. Furniss, T. (1991). The multi-professional handbook of child sexual abuse: Integrated management, therapy and legal intervention. London: Routledge, 1991. Government of Newfoundland and Labrador (1993). Provincial child abuse policy and guidelines. St. John's: Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Department of Education, Division of Student Support Service. Government of Newfoundland and Labrador (1995). Classroom Issues Committee: Report to the Social Policy Committee of the Provincial Cabinet. St. John's: Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Department of Education, Division of Student Support Service. Government of Newfoundland and Labrador (1996). Model for the coordination of services to children and youth with special needs in Newfoundland and Labrador. St. Johns: Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Government of Newfoundland and Labrador (1997). Coordination of services to children and youth: Individual support services plan. St. Johns: Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, Departments of Education, Health, Justice, and Social Services. Haase, C. & Kempe, R.S. (1990). The school and protective services. Education and Urban Society, 22, 258-269. Hunter, R., Yuille, J., & Harvey, W. (1990). A coordinated approach to interviewing in child sexual abuse investigations. Canada's Mental Health, 30 (2&3), 14-18. Kays, Dieter E. (1990). Coordination of child sexual abuse programs. In M. Rothery and G. Cameron (Eds.), Child maltreatment: expanding our concept of healing (pp. 247-257). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Kilker, A. (1989). A police response - devising a code of practice. In H. Blagg, J. Hughes, & C. Wattam (Eds.), Child sexual abuse: Listening, hearing and validating the experiences of children. Harlow, Essex: Longman Group UK Limited. Kinnon, Diane (1988, December). Summary of findings and Conclusions. The other side of the mountain: Working together on domestic violence. Issues Report 1: Interdisciplinary Project on Domestic Violence, Phase 1, Ottawa, Ontario. Martin, M.J. (1992). Child sexual abuse: Preventing continued victimization by the criminal justice system and associated agencies. Family Relations, 41, 330-333. McEvoy, A. (1990). Child abuse law and school policy. Education and Urban Society, 22 (3), 247-257. McGuire, T. & Grant, F. (1991). Understanding child sexual abuse. Ontario: Butterworths Canada Limited. Rogers, Rix (1990). Reaching for solutions: The report of the special adviser to the Minister of National Health and Welfare on child sexual abuse in Canada. Ontario: Health and Welfare Canada. Tite, R. (1993). How teachers define and respond to child abuse: The distinction between theoretical and reportable cases, Child Abuse and Neglect: The International Journal, 17, 5, 591-603. Tite, R. (1994). Muddling through: The procedural marginalization of child abuse, Interchange, 25, 1, 87-108. Tite, R. (1996). Child abuse and teachers' work: The voice of frustration. In In Epp, J. and Watkinson, A. (Eds.), Systemic Violence: How Schools Hurt Children. London: Falmer Press, 50-65. Tite, R. & Hicks, C. (1998). Professionals' attitudes about victims of child sexual abuse: Implications for collaborative child protection teams. Child and Family Social Work, 3, 37-48. Trute, B., Adkins, E., & MacDonald, G. (1992). Professional attitudes regarding the sexual abuse of children: Comparing police, child welfare and community mental health. Child Abuse & Neglect, 16, 359-368. Zellman, G. (1990). Linking schools and social services: The case of child abuse reporting. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 12 (1), 41-45. Zellman, G. & Antler, S. (1990). Mandated reporters and CPS: A study in frustration. Public Welfare, 48 (1), 30-37. |