|

EDUCATION IN NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR Joan E. Netten

Elizabeth Murphy

Because of its relative newness, many educators not directly involved

with French first-language education may be unfamiliar with the program,

or with its characteristics, aims, history, and challenges. The purpose

of this article is to provide such information, with an emphasis on the

Newfoundland context.

Characteristics and Aims French first-language (FFL) education is a program designed for

French-speaking students in which French is the language of instruction

in the classroom for all of the subject areas except English language arts.

French is also the means of communication in the school environment.

The purposes of the program are two-fold:

(1) to provide appropriate educational experiences in order to ensure the social, emotional and intellectual development of all students; and

The specific objectives of the French school are to stimulate and strengthen the learner's sense of cultural and linguistic identity as a francophone; serve as a cultural centre for the French Newfoundland community; reinforce the learner's sense of belonging to the immediate francophone community... provide the learner with the opportunity to develop a good knowledge of the history of the French Canadian people. (Province of Newfoundland, 1991a, pp. 5-6) To achieve these aims, French is used as the language of instruction and administration in the school. All teachers and personnel are expected to be francophone. Most importantly, "the school encourages parental participation in school matters... and creates and maintains close ties with the francophone community of the immediate vicinity as well as with other francophone communities" (Province of Newfoundland, 1991 a, p. 4). One of the major adjustments needed in order to initiate a FFL program in Newfoundland was the development of school-leaving requirements for francophone students. These students are subject to requirements similar to those for anglophones with the exception of the relative importance of English and French as language requirements. The differing language requirements reflect the linguistic and cultural goals of the FFL system as well as the ways in which the program is different from the anglophone programs, including French immersion. In fact, FFL education is quite distinct from French immersion (Fl) although some similarities in curriculum exist. FI is a second-language program designed to teach French to those whose mother tongue is not French by immersing the student in a French language environment in the classroom. Teachers are fluent in French but may or may not be francophone. Curriculum materials used are often those prepared for use in FFL programs, although, with tremendous expansion of FI education in Canada, new curriculum resources are being developed which are prepared specifically for the FI student. Learning materials prepared specifically for FI pupils tend to be somewhat simpler in vocabulary and grammatical structures than those used by native francophones. A considerable difference between the two programs is the amount of instructional time in French. In the FI program, instructional time in French decreases in favour of English as the student advances through the program. The aim is to make students fluent in French without negatively affecting their English language skills. In contrast, in the FFL program, the percentage of instructional time in English remains the same throughout the program with the emphasis being on the development of French language skills. These distinctions may seem rather subtle but are of major importance in order to understand the two programs and the second language acquisition theories on which they are based. In essence, FFL education is, in most provinces including Newfoundland and Labrador, a minority-language program, whereas F1 was conceived as a program for the "majority" child. Basically, the majority child lives in an environment in which the language spoken at home is reinforced by the surrounding community whereas the minority child lives in an environment in which his or her first language is not strongly supported outside of the home of the school. It is for this reason that FFL education, as is the case in Newfoundland and Labrador, is often called French minority-language education which "refers to the opportunity for those people who do not speak the language of the majority to receive schooling in their mother tongue" (Province of Newfoundland, 1986, p. 49). The distinction between majority and minority describes the sociolinguistic milieu within which schooling is provided and is the determining factor in designing the two programs (See Lambert, 1967; Cummins, 1978). The role of the home language is important in determining appropriate

educational experiences for learning more than one language. Research

has shown that a majority child can be placed in a home/school language

switch situation without risk to linguistic development of the home language

or academic success (Swain, 1974; wain and Lapkin, 1982). This view

underlies the FI program. However, research has also shown that a

minority language child needs to receive schooling in the home language

if optimum linguistic competence in both languages and academic success

is o be achieved (Cummins, 1981; Landry, 1982, 1984; Swain and Lapkin,

1991). This view supports the development of FFL education in Canada.

French First-Language Education in Canada In 1969, the adoption of the Official Languages Act accorded equal

status, rights and privileges to English and French languages in Canada.

In 1970, the Government of Canada instituted a program of financial contributions

to the provinces "aimed at giving official-language minorities the opportunity

to be educated or have their children educated in their own language" (Commissioner

of Official Languages, 1990, p. 10). However, for francophone minorities

in many provinces, economic support was not sufficient. Political

or constitutional recognition of minority-language education rights was

necessary. In 1982, Section 23 of the Canadian Charter of Rights

and Freedoms provided this recognition and guaranteed the linguistic rights

of both official language groups as well as the right to minority-language

education. In brief, Section 23 guarantees that a parent has the

right for his/her child to be educated in French if either parent

satisfies any of the following criteria:

- his or her first language learned and still understood is French

French First-Language Education in Newfoundland and Labrador According to the 1991 census, the ,400 francophones in Newfoundland and Labrador represent approximately .04% of the population of the province and are concentrated primarily on the Port-au-Port Peninsula, in Labrador City and in St. John's (Canada, 1991). It is interesting to note that the three francophone communities in the province have different characteristics due primarily to their origins and development, and consequently, somewhat different educational needs. The largest group of francophones resides on the Port-au-Port peninsula where 11 percent of the peninsula's population of 5,245 claim French ancestry, having descended from French fishermen from France, Saint Pierre et Miquelon, Acadia and the Magdelan Islands. This group is the most indigenous, homogenous and stable population, but also the most assimilated. The population in St. John's is the most recent, the least homogenous, and the most transitory. Francophones in St. John's come from the various provinces of Canada, as well as Saint Pierre, France, Belgium, and other parts of the world. They are generally professionals who have come to work either in the schools, the university, or in government. The francophones of Labrador City came to Newfoundland in the sixties to work in the iron ore mines which were developing at that time. They are a relatively homogenous and stable group, with origins primarily in Quebec, although currently threatened by declining numbers and poor economic prospects. The earliest French first-language classes were established in Labrador City in 1960 in order to accommodate children of francophone miners from Qu6bec and New Brunswick. The Labrador Roman Catholic School Board, in two of its schools, Notre Dame Academy and Labrador City Collegiate, has provided French education to these students using a curriculum from Québec. For their final year of high school, these students attend a school in Fermont, Québec, where they may pursue their studies at a College d'enseignement general et professional (Cégep). Many of these students pursue post-secondary education programs in Québec. In 1975, a FI Kindergarten was established at Our Lady of the

Cape Primary School at Cape St.-Georges n the Port-au-Port Peninsula marking

he beginning of FI education in the province. However, attempts at

maintaining the French language and culture of the region were hindered

by the dominance of anglophone culture and institutions. For many

years, not only was education available solely in English, but use of the

French language in schools was often discouraged and, at times, forbidden.

Initially, it was thought that the FI program could respond to the linguistic

and cultural needs of the francophone community. However, it soon

became evident that, as a program designed for anglophones learning a second

language, immersion did not respond to the desires of the francophone community

to restore its French language and heritage. In the Report of the

Policy Advisory Committee on French Programs, the members recommended

that the government of Newfoundland and Labrador recognize that the French language school is the type of school which best meets the objectives of preserving and strengthening the language and culture of francophone students. (Province of Newfoundland 1986, p. 52)The Committee further stressed that from the perspective of language development, the needs of minority language pupils differ from those of pupils who have a totally English language background. If education is not provided in their mother tongue there is a very real danger of complete assimilation of these pupils over a period of time. (Province of Newfoundland, 1986, p. 52)

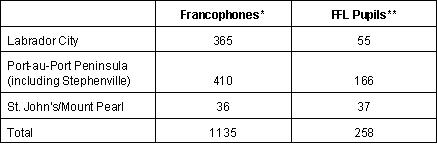

In St. John's, the FFL classes opened in September, 1990, at Ecole St. Patrick, after a period of lobbying and negotiation which began in 1987. At that time, a petition containing the names of 23 students requesting the establishment of FFL classes was sent to the Roman Catholic School Board for St. John's. When the school board rejected the petition, a committee of parents was formed to lobby for the classes. The committee of parents was formed to lobby for the classes. The committee submitted a formal proposal to the board requesting the start-up of a French section in a FI school. In January, 1988, the board conducted a registration to estimate he demand for French programs. hen only 17 children registered, the board refused to set up French classes. After an appeal by the parents to the Department of Education, the Minister created an advisory committee to study the problem. This committee made certain recommendations but negotiations ended because the parents perceived no commitment on the part of government to francophone education in the province. In August, 1988, the parents decided to take their case before the courts under Section 23 of The Charter and named the provincial government and the school board as defendants. The parents' committee then joined other parents' committees in the province forming La Fédération des parents francophones de Terre-Neuve et du Labrador (FPFTNL) which received financial assistance from the Department of the Secretary of State to help in its efforts to obtain French education in Newfoundland and Labrador. A date was set for the court case. However, due to a change in government, negotiations were reopened to settle the problem out of court. As part of the new attempt at resolving the problem, a survey was conducted to determine the number of francophones in the region. The conclusion of the survey, which was conducted by a third party, was that there were sufficient numbers to offer registration. Following the survey, the two parties entered into negotiations which led to an out-of-court settlement. After three years of negotiations, FFL classes began in September, 1990 in St. John's (FPFTNL, 1990). During the 1992-93 school year, a total of 258 students were enroled in FFL classes in Newfoundland and Labrador as indicated in Table 1. TABLE 1

*Source: Statistics Canada, 1991 Census

All of these students attended Roman schools in St. John's, in City

or on the Port-au-Port. The French-only school in Grand'Terre on

the Port-au-Port Peninsula operates classes from K-8 with a total enrolment

of 71 students. Another 68 students were enroled in the K-8 all-French

school in Cape St. Georges and 27 were enroled in the 9-12 dual-track school

(English and French Streams). In Labrador, where FFL education takes

place in classes in 2 schools (one K-6 and one 7-10), enrolment totalled

55. The 37 pupils in FFL classes in St. John's are enroled in Kindergarten

to Grade 5. As may be inferred, a multi-grading situation exists

for some classes in all three areas.

Challenges and Problems The establishment of FFL schooling in the province has not been an easy task. In addition to the preparation of school-leaving requirements, it has been necessary to find appropriate learning resources to support the curriculum, to adopt and modify curriculum documents, to develop guides for the teaching of language arts, in particular, and to undertake considerable in-service preparation of teachers. This work could not be adequately performed without the addition of an FFL consultant at the Department of Education and assistance from other provinces where FFL education was already in progress. The differences among the three communities also create challenges. While the general aims of FFL education are accepted by all, the route to educational success may not be the same in all three communities due to the educational and social background of the parents, the strength of the linguistic heritage of each group and the length of time FFL education has been available to each community (See Netten, 1992). Proficiency in French on entry to the program varies widely. It will take time to introduce a new provincially developed curriculum into the long tradition of a strong Québec-based program in Labrador, to develop an indigenous FFL trained teaching population in the Port-au-Port Peninsula and to build a strong program in the St. John's area that will correspond to the needs of the entire francophone community. There is also the difficult question of governance. In order

for the FFL program to respond to the needs of the francophone community,

control and management of the program must in some way and to some degree

be granted to those who legally hold ownership (Martel, 1991; Foucher,

1991). In the precedent-setting Mahé case (1990), the courts

established a "sliding scale" whereby the degree of management and control

would depend on the number of children involved. In the context of

this case, the Supreme Court of Canada also ruled in relation to section

23 that

official-language minorities in all provinces have a constitutional right to participate effectively in the management of the schools their children attend. In the opinion of the court, management and control ensure the vitality of the language and culture of the linguistic minority. (Commissioner of Official Languages, 1990, p. 19)

the francophone population in the area concerned should have a significant amount of control over francophone education; that is to say, francophones should decide on matters referring to curriculum, staffing, and other pedagogical aspects of their schooling. (Province of Newfoundland, 1986, p. 51)

Finally, the most problematic aspect of FFL education in the province

relates to the size of the francophone population. The low number

of francophones participating in FFL education raises questions about the

viability of the program itself, about the feasibility of governance and

about the linguistic, cognitive and social development of the students

involved (See Murphy and Netten, 1993). Yet, without this form of

education, a valuable cultural community risks assimilation.

Conclusions FFL education in Newfoundland and Labrador is a program designed for children whose first language is French but who are immersed in a majority anglophone society. It is a program which aims to reinforce and strengthen the cultural and linguistic identity of francophone communities in the province and improve academic achievement. The pattern of development of this type of education, along with its aims and objectives, raises complex and provocative questions and many issues have yet to be resolved. It is not clear whether the program's aims and objectives can be realized effectively in an essentially anglophone society such as Newfoundland's. The role of parents in control and management of the program will continue to be a subject of debate which may find resolution only in the courtroom. The program's impact on the French communities and cultures of this province has yet to be measured and it is not known whether or not this impact is as intended. Other issues will arise as FFL education grows and expands and hose responsible for the programs ill need to determine answers to broader questions. For example, what is the impact of FFL education on other programs such as Fl? To what extent can the education system provide for the needs of minority groups? Can the province afford to make FFL education work? Can it afford not to? REFERENCES Commissioner of Official Languages (1990). Annual Report to Parliament by the Secretary of State of Canada on his Mandate with Respect to Official Languages. Ottawa. Department of the Secretary of State of Canada. Commissioner of Official Languages (1990a). Annual Report, Part 4: Minorities (Extract). Ottawa: Department of Secretary of State of Canada. Cormier, R., Crocker, R., Netten, J., & Spain, W. (1985). French Educational Needs Assessment, Port-au-Port Peninsula. St. John's, Newfoundland: Institute for Educational Research and Development, Memorial University of Newfoundland. Cummins, J. (1978). Educational implications of mother tongue maintenance in minority-language groups. Canadian Modern Language Review, 34, 395-416. Cummins, J. (1981). The role of primary language development in promoting educational success for language minority students. In California State Department of Education, Schooling and Language Minority Students: A Theoretical Framework. Los Angeles: Evaluation, Assessment and Dissemination Centre. Dallaire, L. (1990). Demolinguistic Profiles of Minority Official-Language Communities. Demolinguistic Profiles, A National Synopsis. Ottawa: Department of the Secretary of State of Canada. Fédération des parents francophones de Terre-Neuve et du Labrador (1990). The Parents Speak Out: A Newsletter from the Fédération des Parents Francophones de Terre-Neuve et du Labrador. Foucher, P. (1991, April). Après Mahé ... Analyse des démarches accomplies et à accomplir dans le dossier de 1'éducation minoritaire au Canada. Education et Francophonie, 19(l), 6-9. Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Our Children, Our Future. St. John's: Queen's Printer, 1992. Lambert, W.E. (1967). A Social Psychology of Bilingualism. Journal of Social Issues, XXIII (2). Landry, R. (1982). Le bilinguisme additif chez les francophones minoritaires du Canada. Revue des sciences de I'éducation, 8, 223-244. Landry, R. (1984). Bilinguisme additif et bilinguisme soustractif. In A. Prujiner et al., Variation du Comportement Langagier Lorsque Deux Langues Sont en Contact. Québec: Centre international sur le bilinguisme. Martel, A. (1991). Official Language Minority Education Rights in Canada: From Instruction to Management. Ottawa: Government of Canada, Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages. Murphy, E. & J. Netten (1993). Défis et problèmes relatifs à 1'enseignement du français langue première en milieu minoritaire. Communication présentée au congrès annuel de I'association canadienne de la linguistique appliquée. Ottawa, Université Carleton, juin, 1993. Netten, J. (1992). Les trois communantés francophones à Terre-Neuve: I'unité et la diversité. Communication présenteé au congrès annuel de I'association canadienne de la linquistique appliquée, Moncton, Université de Moncton, juin, 1992. Province of Newfoundland (1984). The Aims of Public Education for Newfoundland and Labrador, Department of Education, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Province of Newfoundland (1986). Report of the Policy Advisory Committee on French Programs to the Minister of Education, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Province of Newfoundland (1991a). A Policy for French First-Language Education in Newfoundland and Labrador. Department of Education, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, Division of Program Development. Province of Newfoundland (1991b). Education Statistics: Elementary-Secondary. Department of Education, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, Division of Research and Policy. Swain, M. (1974). French immersion programs across Canada. Canadian Modern Language Review, 31,117-129. Swain, M. and S. Lapkin (1982). Evaluating Bilingual Education: A Canadian Case Study. Clevedon, England: Multi-Lingual Matters. Swain, M. and S. Lapkin (1991). Heritage language children in an English-French bilingual program. Canadian Modern Language Review, 47, 635-641. |