|

NEWFOUNDLAND (1993) Jeff Bulcock

Ron Dawe

Purpose The question addressed in this paper is: To what extent

does equality of educational attainment prevail in Newfoundland?

In particular we are interested in whether the equality of educational

attainment holds for subgroups in the population based on the following

ascribed criteria: gender, age, religious membership, type of community

and region.

Background Concern about inequities in educational opportunity arose in the post-World War II era with the consequence that the governments in virtually all Western nations, no matter whether to the right or left of the political spectrum, and no matter which side of the Atlantic, subscribed to the equal opportunity principle. The principle holds that everyone should have an equal chance to achieve the benefits and rewards that a society makes available; that there should be no artificial barriers holding some people back; and that there should be no special privileges giving some unfair advantages over others. It is for these reasons that equality is usually coupled with the concept of justice. It flows from this that the society which adheres to the equality principle will disallow discrimination which bars people of a particular gender, religion, or ethnicity from careers or public offices. And this means that all children and youth must be given an equal start through provision of equal or common educational opportunities, thereby giving them an equal chance to develop their talents. While there is little controversy today about the principle of

equal opportunity, the same cannot be said for the policies designed for

achieving it; and, in particular, for a corollary of the principle called

the equality of outputs, or equality of results. While there are

numerous empirical studies on the equality of the resource inputs of schooling,

there are fewer empirical studies dealing with the equality of schooling

outcomes. The reason is fairly obvious: equality of inputs is believed

to be attainable, whereas equality of outputs is not. Currently (1995-96),

the controversy over equality of outcomes is over the question: What

minimal educational provision is each person in society entitled to?

The controversy is less over what resources go into education than over

what kind of product comes out. From the perspective of the school

graduate it is not so much a question, therefore, of how "equal" the school

is, as a question of how well equipped the graduate is to compete on the

open local, provincial, or national labour market on an equal basis with

others, regardless of gender, social origins, community of residence, and

such like. The issue has shifted from one focused on equalizing the

schools to one focused on whether on entry to adult society all children

are equipped to ensure their full participation and potential. Another

way of stating this proposition is to say that schools will be evaluated

primarily in terms of the extent to which they eliminate barriers based

on ascribed criteria. And, first, we have to identify the extent

to which ascribed criteria constitute barriers to full participation, which

is the purpose of this paper.

Research Questions To examine the extent to which educational attainments are equal

across different social groupings we can establish a set of conditional

probabilities; for example,

(i) the probability of high school graduation,

Each research question takes a form parallel to the following:

Are educational attainments conditional upon gender, other things equal?

In other words, can it be said that differences in educational attainments

are attributable to differences in gender when taking the other four conditioning

agents into account simultaneously? The "other things equal" rider

associated with each question is important. It refers to the "other"

potential conditioning agents in the full model. Here we are asking

whether the gender-educational attainment relationship is net of (or over

and above) the effects of age, church membership, community type, and region.

The five conditioning variables are referred to as ascribed criteria because

each represents a quality which, for the most part, is given at birth,

or by the position into which persons are born, hence, over which they

may have little or no control. The outcome variable, educational

attainment, is an achieved quality; that is, something which most individuals

in an open society can attain with appropriate effort, given the opportunity.

Theoretical Framework

Gender Differences The struggle for gender equality has had a tortuous twentieth century history, but the post World War II era proved to be one which was more receptive than prior years to the idea of equal educational and occupational opportunities for women. There is still a tendency to believe that as a social construct men and women, along with the concepts of feminine and masculine, are polar opposites, and as such provide a basis for people's expectations. In this sense, if men are perceived as being adventurous, assertive, and independent, women are expected to be the opposite. The result in practice is that women who may be performing the same job with the same qualifications and experience as men tend to earn less than men. Statistics Canada reports that on average women earn other things equal about 70 per cent of what men do. Despite the well documented evidence of the barriers to equal

opportunity for women, we can find little evidence for inequalities in

educational opportunities for women in Newfoundland. Educational

historian, Phillip McCann, author of Schooling in a Fishing Society, reports

data showing that from 1921 through 1946 a higher proportion of girls attended

school than boys even though 5 to 15 year-old girls constituted a smaller

proportion of the population than boys. For the past decade, girls

have been outperforming boys in Newfoundland schools at every grade level

and in every subject except level 3 physics. In verbal subjects such

as reading, language, religion and social studies, the differences in favour

of girls are pronounced. For the past decade more females than males

have been graduating from Memorial University, and while females are still

underrepresented in the physical sciences, mathematics and engineering,

the female minority in these fields are significantly outperforming their

male counterparts. These are the differences accounting for the fact

that medical school entry, which is based largely on academic performance,

is in favour of females. Given this kind of evidence we conclude

that there are unlikely to be gender differences in educational attainment,

and if there are, they are not likely to be in favour of males.

Age Differences There is ample evidence supporting the negative relationship between age and educational attainment in Newfoundland. Two theories are worthy of consideration: the theory of demographic transition and the theory of human capital. Prior to Commission Government (1934-49), the educational system in Newfoundland was somewhat static. One and two roomed schools were the norm. Few went beyond grade 8. Attendance was voluntary. Over a quarter of the 5 to 15 year-olds did not go to school and attendance among those enrolled in school was little more than 70 per cent. While the Commissioners perceived this as a major problem they were unable to implement changes because the ones imposed tended to infringe on established denominational rights; thus, during the early years of Commission Government the traditional limitations of the educational system were permitted to prevail. For example, though compulsory schooling was advocated by the Commissioners in 1934, they were unable to pass suitable legislation to that effect until 1942, and even then the legislation could not be enforced until about a decade later thanks to a shortage of both schools and teachers. Not surprisingly, Newfoundlanders attending school in these years -- that is, those who in 1993 were in their mid-fifties and older, and especially those from rural settlements -- with but few exceptions tended to have modest levels of formal education. Substantial demographic changes began to occur during the war years (1939-45). The stable demography of the earlier years of the century with its relatively high birth and death rates changed. For example, death rates which in the 1930s hovered around 13 per 1000 began to fall. Today they are around 6 per 1000. According to the theory of demographic transition death rates begin to fall with improvements in nutrition, sanitation, health care and education. These are not documented here except to point out that in 1937 the death rate was 13.5, while by 1947 it was down to 9.9, and by 1952 it had dropped again to 7.5. In this early stage of transition the birth rate remained high; hence, there was substantial population g rowth. In 1945 the population of the province was 290 thousand. Thirty years later, in 1975, and despite sustained out migration, it was 550 thousand, an increase of 90 per cent. These changes were accompanied by shifts in social attitudes toward education, health, contraceptive use, and technology. Higher living standards, thanks to some extent to the war economy, were accompanied by an increased demand for education, by increasing life expectancy, and reductions in fertility. The 1955 birth rate of 36.3 -- probably the highest in the English speaking world -- by 1985 had dropped to 14.6 and was still dropping. To replace a population, fertility rates must be 2.1 or higher. In 1993 the rate was beginning to level out at 1.5, which is well below the replacement level, and below the prevailing Canadian rate of 1.7. In terms of demand for education, the proportion of provincial government revenues earmarked for education was already one fifth (21 per cent) of the provincial budget in 1950, and by 1970 had risen to 30 per cent of the total provincial budget. In the late 1950s and early 60s economists were showing that investing in people yielded high dividends in terms of living standards. The classic example is Japan, a country in which people early recognized that the education and skills of its work force constituted its most powerful competitive weapon. The political goals of the period included both better health and education as a way of improving what the economists called human capital. Individuals, by investing in both, were increasing their worth to a future employer, and in the general case the amount of the investment was found to be reflected in their pay. The incentive to invest by both individuals and governments was considerable since there proved to be substantial returns to both private and social investments. The age factor for three reasons, therefore, should account for

differential educational attainments. First, the war time changes

to a formerly stagnant provincial economy triggered demographic changes

manifest as declining death rates and the beginnings of the post-war baby

boom. As the economy grew the advantages to both individual and social

investments in education became increasingly obvious, triggering a greater

demand for schooling. Accompanying these powerful demographic shifts

were substantial cultural changes as the province moved from a predominantly

rural to a more urbanized society, a condition congruent with yet further

educational expansion. Today's elderly while not necessarily benefitting

personally have lived through an educational revolution, a revolution which

was accompanied by demographic transition: from a prewar static stage

with high birth and death rates, followed by rapid economic growth accompanied

by even higher birth rates but declining death rates , followed finally

in the 1970s to the present day by demographic slowdown. In each

stage the demographic changes following a lag were accompanied by parallel

economic and educational changes. Currently, following birth rates well

below replacement, both the economy and the educational system seem to

have stagnated. The evidence is that we are again entering a period

of slow economic growth in which there is little room for further educational

expansion even though our educational infrastructure falls short of that

existing in other educational jurisdictions. Nevertheless, on the

basis of these arguments we expect to find that each generation from the

Commission Government era onward will be characterized by successively

higher educational attainments. Both higher living standards and

low student/worker ratios, thanks to the baby boom, support educational

investments and the subsequent educational expansion.

Religious Membership Here we address the question: What grounds justify the hypothesis of a relationship between church membership and educational attainment? Do the members of some denominations invest more in intellectual competencies than others, and, if so, why? We address two theories posited by Adam Smith (1775) and Max Weber (1904-05). Smith in his classic work on "An Investigation into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations" provided an explanation for the birth of new religious organizations. He noted that as churches prosper, they become better endowed, and more firmly established in the eyes of the law, while at the same time there is a tendency for them to become less responsive to the spiritual needs of their congregations. He wrote that in such circumstances the clergy, "reposing themselves on their benefices [neglect] to keep up the fervour of the faith and devotion in the ... people; and [to] become altogether incapable of making any vigorous exertion in defense even of their own establishment." This lack of vitality, according to Smith, was in part due to the fact that stipends were awarded to "churchmen" regardless of their effectiveness either as preachers or proselytizers. Such complacency, he argued, would eventually lead to a spiritual vacuum which would be met by dissenting clergy, who would likely "...inspire [their congregation] with the most virulent abhorrence of all other sects." In Smith's day, but not in ours, the mechanism accounting for the emergence of dissenting clergy would seem to operate solely in the Protestant camp, but not in the case of the Roman Catholic Church. Smith gave two explanations for this. First, he pointed out that a monetary incentive prevailed in the Catholic Church since the "inferior" clergy at the parish level depended on their parishioners for part of their income. Second, in times when the church fell into disfavour in Europe the mendicant orders "revived ... the languishing faith and devotion of the Catholic Church." Since the sustenance of the mendicants depended "altogether on their industry" they were "obliged, therefore, to use every art which can animate the devotion of the common people." Smith extended this argument by noting that "the advantage in point of learning and good writing [would] be on the side of the established church." He concludes, therefore, that the smaller, non-mainline denominations would place less emphasis on learning and more on preaching and proselytizing. In Newfoundland there are three mainline, well established denominations; the Roman Catholic Church, the Anglican Church, and the United Church with 37 per cent, 26 per cent, and 17 per cent of the population respectively. For details see Table A1 in the statistical appendix. Non-mainline denominations would include the Salvation Army, the Pentecostal Assemblies and a half dozen or so small, mostly fundamentalist sects. Today the Salvationists constitute 8 per cent of the population and the Pentecostalists 7 per cent. It would be congruent with Smith's thesis to posit two hypotheses: first, that educational attainments of the population would be higher among the adherents of the mainline churches than those in the non-mainline denominations; and, second, that there are unlikely to be aggregate differences in educational attainments between the adherents of the mainline churches themselves. Weber's views differed from those of Smith. Weber's claim was that while the cultural changes brought about by the Protestant Ethic may not have been the cause, or the direct cause of capitalism, nevertheless, the ethic did provide a culture supportive of individualism, hard work, and self-reliance. In this sense capitalism was probably dependent on religious legitimation. In the Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, first written in 1904-05, Weber argued that Protestants lacked confidence in their own personal salvation. This view was based on the belief that only "the elect" were predestined for salvation. Their response to such "salvation anxiety" was hard work, self control, communal service, and reading the scriptures on the grounds that these might possibly be signs of "election". Coincidentally, these were the very qualities that enabled individuals to excel and prosper in worldly affairs. In contrast, Weber noted that Catholics believed that salvation was attainable through institutional means; that is, via the Church's mediation through the confessional, baptism, and communion. The empirical status of Weber's thesis was given credence by Gerhard Lenski, an American sociologist, who in the 1960s, found on the basis of his Detroit Area Study that working class Catholics largely supported working class values , while working class Protestants largely supported middle class values. Compared to Catholics, Protestants had smaller families; considered work more important, saved their money; voted Republican; migrated to obtain an education or a better job; and developed a greater commitment to intellectual autonomy. And because the Protestant middle class believed in making substantial educational investments for their children Lenski was not surprised to find that a disproportionately high number of Protestants compared to Catholics were upwardly mobile, and had higher levels of educational attainment. The church membership-educational attainment argument was also promoted by Lenski's findings that urban dwellers preferred face-to-face, personal relationships to impersonal, secondary-type relationships. He was able to show that this desire for primary group, personal relationships was often satisfied through membership of a neighbourhood church. Neighbourhoods, however, tended to be segregated along both economic and ethnic lines; hence there was a powerful tendency for churches over time to become differentiated on the basis of social class, so much so that church membership often became a badge of one's social standing. As neighbourhoods changed so did the churches. Because like attracted like, congregations tended to become composed of families with similar values, life styles and educational levels. The findings from the Detroit Area Study were unambiguous; namely, that the mainline Protestant congregation was for the most part better educated than the typical Catholic congregation. But this argument carries little weight in Newfoundland. Since Confederation, the Catholic church in Newfoundland despite its other-worldly orientation and its traditional conservative distrust of Modernism, has materially benefitted from its growing urban base. Today Catholics in Newfoundland are as likely as Protestants to hold managerial positions, to hold elected office, to have equal media access, to be members of the professions, and to be well-educated. There is a sense, then, in Weberian terms, in which the Catholic Church in Newfoundland has become protestantized. Given these arguments one should expect few if any educational differences between the Catholic and mainline Protestant populations of Newfoundland. It is on the basis of these arguments that we predict that there

are unlikely to be educational differences between the Catholic Church

members and the adherents of the Anglican and United Churches. The

adherents of the non-mainline Protestant denominations (though there are

many exceptions) are likely to be, in aggregate, less well educated.

At the top of the hierarchy, as at the bottom, there may be unmet spiritual

needs. In theory, those falling into this category are likely to

be highly educated -- e.g., the non-Christians and the unbelievers.

Type of Community This section of the paper is concerned with whether place of residence affects educational attainment. While we focus on the rural community of less than 1,000 people, which is where 46 per cent of the Newfoundland population live today, we emphasize that the concept "rural" only assumes meaning in the context of its counterpart "urban"; that is, only when the culture of country life is contrasted with town life. The empirical evidence from Newfoundland data overwhelmingly shows that rural populations are less well educated than urban populations; and that with but few exceptions rural students in all school subjects perform at levels below those attained by urban students. The question addressed here, then, is why have such differences occurred. The first point to note is that the phenomenon is not unique to Newfoundland. It is found to the same degree in many States of the U.S., and perhaps to a lesser degree in all Canadian provinces. And it is an ongoing concern in virtually all countries in the European Union; indeed, in Britain it was a major reason for introducing the National Curriculum in the Education Reform Act of 1988. Here, we present three arguments to support the hypothesis that urban populations in Newfoundland have higher levels of educational attainment than rural populations. Item #1. Rural communities have benefitted less from the economic developments stemming from the aftermath of World War II than urban communities. Consequently job opportunities have deteriorated over most of this period in rural Newfoundland, and continue to deteriorate. Rural residents with competitive labour market skills, that is those with post secondary education levels, have tended to move into urban labour markets. And with the recent collapse of the traditional fishery many other rural residents have also moved to urban centres both in Newfoundland and the mainland. Item #2. Rural educators face a double challenge, which places greater responsibility on the shoulders of rural educators than urban educators. In the first place, the economies of scale that are associated with the specialized teaching and uni-grade classrooms found in urban school systems, are not options for rural educators. Rural schooling, then, is inherently less cost effective than urban schooling, a fact which is rarely taken into account in the Government's policy of equal treatment. Yet to treat people equally when they are different in relevant ways is unjust. Further, given the high unemployment levels in rural areas, many rural youth will only find employment on the urban labour market. This, in turn, means that the rural educator has a mandate for teaching the values and skills which will enable rural youth to compete on equal terms with their urban counterparts; values and skills, moreover, which if exercised could easily contribute further to the underdevelopment of rural Newfoundland. Policies based on educating rural youth for the urban job market might well exacerbate the problems with the rural economy. Item #3. Traditionally, rural economies, largely dependent as they are on natural resource development, rarely required workers with advanced academic training and/or specialized technical skills. Thus, traditionally it was always a student minority who, wishing to further their education at the post-secondary level, were willing to subordinate rural values to those congruent with success in post-secondary education. Thus, the values of rural educators tend to be at odds with those held by the parents of their pupils. In terms of prevailing ideology the successful rural school is one which does the best job of training students for export -- a policy unlikely to find support in much of rural Newfoundland because it fails to support rural life styles and values. Consider this view expressed by a teacher of vocational education

in a rural school system.

To have a saleable skill is a value to most of our families here. For example, in our vocational program we have no problems with parents. None. They love what we're doing because it fits their norm; whereas in academia they have problem after problem. It is difficult for parents to relate to the need for academic skills as far as earning a living because most of them don't have such skills either. And most are not mobile anyway. They want to live here. They want to stay here. ...

Regional Differences Should we expect to find regional differences in educational attainments, over and above urban-rural differences; or are urban-rural differences mere proxies for regional differences, or vice versa? Regional differences at the national level, especially by province, have been well documented by Statistics Canada, especially in terms of per capita income, employment rates, and educational levels. Less well understood and documented are the regional disparities within provinces; nevertheless, few would deny that in most provinces there are regions of underdevelopment. In Newfoundland the underdeveloped regions are dependent on the export of raw products such as ground fish, lumber, and metal bearing ores. Underdeveloped regions are overwhelmingly rural and characterized by a low division of labour, and isolation in terms of access to post-secondary educational institutions. In political terms they have modest influence at best. The Labrador coast, the Northern Peninsul a, the Baie Verte Peninsula, and the South Coast come to the mind of those familiar with the Provincial economy. Most people in these regions are fisher-folk. They are more

economically self sufficient than most Canadians. They live in small

coastal settlements, seldom more than 1000 persons, and fewer than 200

households. They do not constitute a single class, but can be differentiated

in terms of their degree of ownership of their trapskiffs, longliners,

marine engines, and fishing gear. They are suffering today because

their fishing grounds have been overfished by the factory ships and trawlers

of the corporate fishing fleets, both Canadian and European, with the result

that the ground fish population has been reduced to very low levels, while

at the same time the marine ecosystems have been impoverished and destabilized.

Ironically, the zero-sum drive for short-term profits (or "madhouse economics")

has reduced, not increased jobs, and there is still no consensus about

how to restore the ecological balance. The simple fact is, however,

that it will require substantial structural reforms to the industry, including

a marked reduction (even phase out) of the over-capitalized corporate fishing

fleets on the grounds that their methods are too efficient. The economic

needs of corporate capitalism have been permitted to override the social

needs of regional Newfoundland economies. The purpose of restructuring

would be to lessen pressure on fish populations and to increase employment

in the fishery.

Hypotheses On the basis of the arguments presented in the preceding sections

we have derived the following hypotheses: (i) that there are few

grounds on which to claim that gender differences account for educational

attainments; (ii) that educational opportunities have consistently improved

over the past half century with the result that in aggregate today's young

adults are substantially better educated than today's elderly; (iii) that

it is unlikely that there will be educational differences between Catholics

and the members of the mainline Protestant denominations (the Anglican

and United Church members); (iv) that the adherents of the non-mainline

Protestant denominations are unlikely to be as well educated as the mainline

Protestants, while the non-Christian/no religious affiliation group is

likely to consist of highly educated persons; (v) that the type of community

is likely to be a factor accounting for educational attainment, in favour

of the residents of urban communities; and (vi) that over and above the

effects of community type there are likely to be regional differences in

educational attainments.

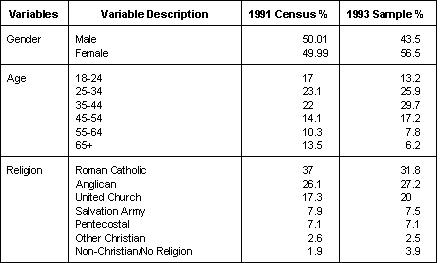

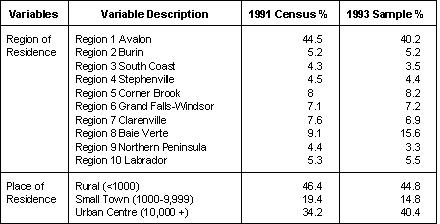

Methodology Data The public opinion poll data was gathered by Omnifacts Research of St. John's on behalf of the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador in October 1993. It was a follow-up to an almost identical survey conducted in November 1991 by Research Associates of St. John's on behalf of the Royal Commission on Primary, Elementary and Secondary Education. Both surveys were designed to assess public attitudes toward the role of religious denominations in the governance of the provincial school system. The 1993 survey was a 44 question, telephone survey of 1153 randomly selected respondents 18 years of age and older. Sample While the initial sample consisted of 1153 randomly selected respondents the Government requested the polling firm to overrepresent the Pentecostal minority; thus, the initial sample included 313 Pentecostal adherents or 27 percent of the total. Because the proportion of Pentecostal population in Newfoundland is reported by the 1991 Canadian Census as being 7 per cent we weighted the Pentecostal responses (WGHT=.204) to reflect the true Pentecostal representation in the Province, that is, to some 64 Pentecostal adherents, which resulted in 904 cases for the purposes of the present analysis. The margin of error for a random sample of this size is ±4 percentage points 19 times out of 20. Sample accuracy can be ascertaine d by comparing the known characteristics of the present sample with parallel characteristics from the 1991 Census, as shown in Table A1 in the statistical appendix. With reference to Table A1, the gender percentages could have been a little closer. Three denominations, the Catholics, Salvationists and Other Christian, were modestly underrepresented while the other four religious groups were marginally overrepresented. Differences in Type of Community and Region were minor except in one instance; namely, region #8 (Baie Verte). Here the difference of over six percentage points (9.1 percent of the population in the 1991 census were from the Baie Verte region whereas our sample population consisted of 15.6 per cent of the population) requires explanation. This region is the Provincial Pentecostal stronghold. To over-sample the Pentecostals as Government. Table A1. Comparison of 1991 Census and 1993 Public Opinion Poll Sample1

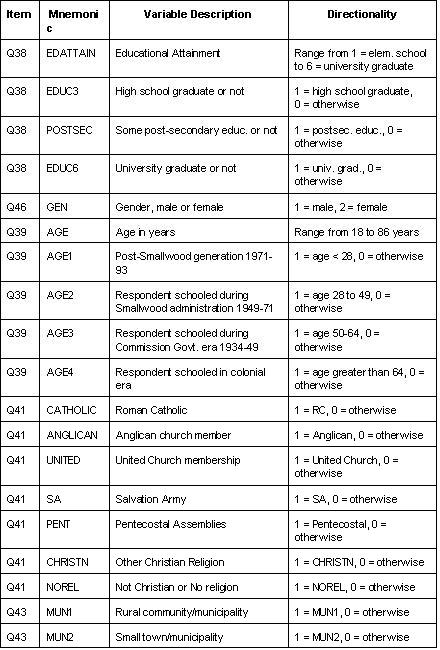

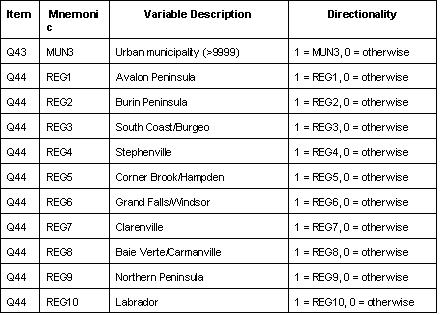

1. The 1991 Census data were derived from several Statistics Canada sources; specifically the following: Age, Sex, and Marital Status, Table 1 (p. 7) and Table 4 (p. 100); Religions in Canada, Table 2 (pp. 20-22); and Urban Areas, Table 3 (p. 62) and Table 4 (pp. 68-75).requested, the polling firm had to over-sample the residents of this region. In doing so they not only oversampled Pentecostals but also other Christian groups by 6 percent. Variables The models to be estimated in this study in order to confirm or falsify the hypotheses consist of 30 variables of which 28 are dummy variables. The age variable is interval and the educational attainment variable is ordinal. Variable descriptions and their directionalities are to be found in Table A2 in the Statistical Appendix. The age variable was broken down into four categories representing political eras. Category #1 included the young adults who were educated largely during the Moores' administration beginning in 1972 and who in 1993 were aged 18 to 27. Those aged 28 to 49 were educated during the years of the Smallwood administration 1949-1971; those aged 50 to 64 were educated in the Commission Government years; while the 65-86 year-olds were educated in the Colonial era. This odd categorization was designed to test a supplementary hypothesis. There is some debate about the effectiveness of the Commission Government years 1934-1949 in terms of educational progress. It is claimed, for example, that they were years of stagnation, years when the government's mandate was effectively to preserve the status quo ante, thus lacking the progress found under later administrations. The categorization specified in this study will test such claims in terms of educational attainment. Table A2. Questionnaire Item, Mnemonic, Variable Description

Religious membership was included as a set of seven categories. Five of these were unambiguous -- Roman Catholic, Anglican, United Church, Salvation Army and Pentecostal Assemblies. Greater detail is provided in Table A1. Some 23 respondents belonged to small (in Newfoundland) Christian congregations such as the Apostolic, Christadelphian, Christian Bretheren, Gospel Hall, Baptist and Presbyterian. These were combined into a single category and labeled "other Christian". The 35 respondents who identified themselves as belonging to religions other than Christian, or who had no religious affiliation, were also combined into a single category labeled "no religion". The type of community or place of residence was a three point

classification; namely, (i) a rural community with less than 1,000 people,

(ii) a small urban area with a population at the time of the 1991 census

of between 1,000 and 9,999, and (iii) urban municipalities with 10,000

or more people. Because it was thought that region of residence could also

be a factor accounting for educational opportunity over and above community

type, the Province was divided into the ten regions representing the proposed

new school districts which closely resemble those boundaries called for

by the Royal Commission on Education which reported in 1992.

Findings This study is concerned with the extent to which five ascribed

factors account for the educational attainments of adult Newfoundlanders.

These factors were: gender, age, religious affiliation, place of

residence, and region of residence. As a side issue we also address

the question as to whether in educational terms the Commission Government

era (1934-49) was a stagnant period in Newfoundland's history. The

research questions were framed as conditional probabilities; namely the

probability of graduation from high school, the probability of post-secondary

education participation, and the probability of university graduation.

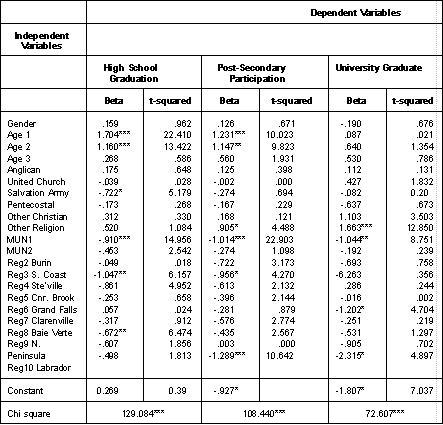

The findings are presented in Table A3.

1. In terms of the probabilities of high school graduation, post-secondary participation and university graduation there were no gender differences identified. As hypothesized for the reasons given above the findings support the "null hypothesis" of no difference.

* p<.05; **p<.01; ***p <.001 5. Both community type and region of residence accounted for each of the three conditional probabilities, essentially as hypothesized. There were no differences between the urban centres and small municipalities in terms of the three probabilities, while, in contrast, residence in a small rural settlement proved a substantial barrier to educational achievement. There is no doubt on the basis of these (Table A3) findings that both urban and small town dwellers are educationally advantaged in terms of high school graduation, post-secondary participation, and university graduation. Pockets of educational disadvantage were also located in several regions of the Province. Compared to the Avalon region all other regions to varying degrees were educationally disadvantaged, but in most cases the differences were not statistically significant. Exceptions, however, included regions 3 and 10 (the South Coast and Labrador) which were disadvantaged on two out of the three criteria of educational opportunity; while regions 4 and 8 (Stephenville and Baie Verte) were disadvantaged in terms of high school graduation; and, finally, residents of region 6 (Grand Falls/Windsor) were disadvantaged in terms of the opportunity to graduate from university. This study of the equality of educational achievement in Newfoundland has focused on five ascribed criteria, each of which, potentially, could constitute a barrier to the attainment of an individual's educational potential and therefore to full participation in Canadian society. We argued that in Newfoundland it was unlikely that barriers to educational attainment would be found on the basis of gender; and this hunch was supported by the analysis. And, as expected, we found that the substantial improvements in the Provincial economy over the past half century were accompanied by considerable educational expansion, followed by the progressively higher educational attainments of subsequent generations. By the same token as the barriers to educational attainments on the basis of age dissolve through attrition -- as the older generations die off -- we can expect the age factor as a barrier to decline. We also found barriers, as expected, in terms of religious membership. But these were far less than we anticipated on the basis of our theorizing. Salvationists were less likely to have completed high school than the members of other Christian denominations. And the members of the mainline denominations were far less likely to have completed post-secondary schooling than either non-Christians or those with no religious affiliation. This finding gives rise to two questions, namely, (i) Is being a Christian these days a handicapping condition in so far as the attainment of higher education is concerned, or does having a higher education tend to promote agnosticism? and (ii) Whatever the answer to the first question, is it culturally problematic? Notwithstanding the effects of age and religious membership discussed

above, the two factors which accounted most for the magnitude of the disparities

in educational attainments, were the type of community in which a person

resides and the region of the province where the community is located.

Fact number one is that Newfoundlanders living in small rural settlements

of less than 1,000 persons have educational attainment levels well below

those living in the urban centres and small towns and that, given current

educational policies based on equal treatments even for persons who are

not necessarily equal, these inequities are likely to remain. And

fact number two is that persons living on the South Coast, Stephenville,

Baie Verte, and Labrador regions are much less well educated than the residents

of the Avalon Peninsula and the other five regions of the Province; and,

again, given current educational policies, these inequities are likely

to remain unchanged. The ten regions, moreover, are those contiguous

with the ten new school districts proposed by Government on the recommendation

of the Royal Commission on Education. The School Boards in the four

disadvantaged districts will have little chance to improve matters in their

regions if the equality principle is based on the erroneous assumption

that the people in these regions are otherwise equal to those in other

regions in so far as educational treatments are concerned. The evidence

suggests that they are culturally different and that such differences may

justify unequal treatments.

Statistical Appendix Logistic Regression The estimates presented in Table A3 which follow are based on a logistic regression analysis. The logistic model uses a maximum likelihood estimator and is a natural complement of the least squares estimator used by the multiple regression model in the situation where the regress and, or dependent variable, is not continuous but, rather, in a state which may or may not obtain; for example, high school graduation or not, contraction of a disease or not, or voting yes in a government referendum or not. When such variables occur among the regressors of a regression equation they can be dealt with by the introduction of (0, 1) dummy coding; but when the dependent variable is of this type, the regression model breaks down (some key assumptions such as that of bivariate normality are violated). It is in such instances -- i.e., in the case of qualitative dependent variables -- that a log it or logistic model provides an appropriate alternative. Both the multiple regression model and the logistic regression model are designed to address systems of causal relations as opposed to statistical association. Both are designed to be isomorphic to the experimental model where the direction of causality is not in question. Both address models where there is a clear a priori asymmetry between the independent variables (regressors) and the dependent variable (regress and). But unlike regression the logistic model permits interpretation in terms of utility maximization in situations of discrete choice. Regression requires a disturbance term, but like all probability models the random character of the dependent variable in the logistic model flows from the initial specification. Mathematically, the probability of falling into group 1 (not group 0) is expressed as follows. Probability of being in group 1 (e.g., high school graduate) = 1/(1 + e-z)(1) where e is the base of natural logarithms ( 2,718), and Z is estimated from an equation which optimally weights each predictor variable. This necessitates the probability being greater than 0, but less than 1, given Z = Bo + B1X1 + B2X2 + ... + BpXp(2) where Bo is the constant term and B1, B2, and Bp are the coefficients each of which is estimated mathematically to maximize the predictive accuracy of the equation. The mathematical computations are done by computer, being too complex to be done by hand. From the public opinion on education data set used in this study, where 1 = high school graduate, 0 = non-high school graduate equation 2 is (see Table A3): Z = .269 + .159(GEN) + 1.704(AGE1) + 1.160(AGE2) + .268(AGE3) + .175(ANGLICAN)

where the values for the independent variables were obtained from

Table A3. Consider the probability of a 64 year-old Pentecostal man from

Carmanville, a small urban community in the Baie Verte region of the Province,

graduating from high school.

Thus, the probability of high school graduation from equation 1 is: 1/(1 + e-(-.602)) = 1/(1 + e.602) = 1/(1 + 1.826) = 1/2.826 = .354That is, the chances are approximately one in three that this person (or his statistical twin) will have graduated from high school. Suppose, however, that the same person instead of being a resident of Carmanville in the Baie Verte region had been a resident of St. John's. His Z-score would be 0.523; hence the probability of his graduation from high school would be: 1/(1 +e-(.523)) = 1/(1 + .593) = 1/1.593 = .628That is, his probability of graduating from high school will have significantly increased from 35 per cent to 63 per cent. Obviously there are clear educational advantages to being a resident of St. John's on the Avalon Peninsula. Now, consider the probability of a 21 year-old Anglican female from Carbonear graduating from high school Z = .269 + .159(2) + 1.704(1) + .175(1) - .453(1) -.317(1) = 1.696 Thus, the probability of high school graduation is: 1/(1 + e-(1.696)) = 1/(1 + .183) = 1/1.183 = .845Or, her chances are better than 4 out of 5 that she will graduate from high school. Would it have made any difference if this person had been a resident of St. John's? Her Z-score would be 2.466. Thus, her probability of high school graduation had she been a resident of St. John's would have been: 1/(1 + e-(2.466)) = 1/(1 + .085) = 1/1.085 = .922In other words although her probability of graduation from a Carbonear high school was high (84 per cent probability), her chances would have been even higher by an additional 8 per cent had she been a resident of St. John's. Both type of community and region of residence make a difference. |