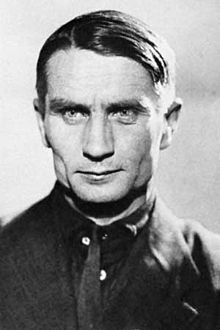

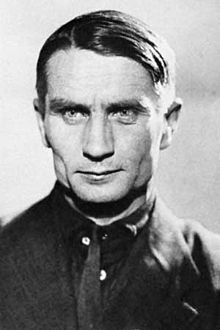

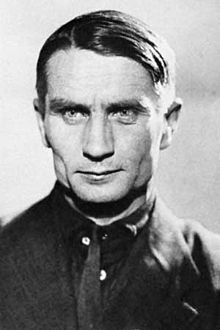

TD Lysenko (1898 - 1976)

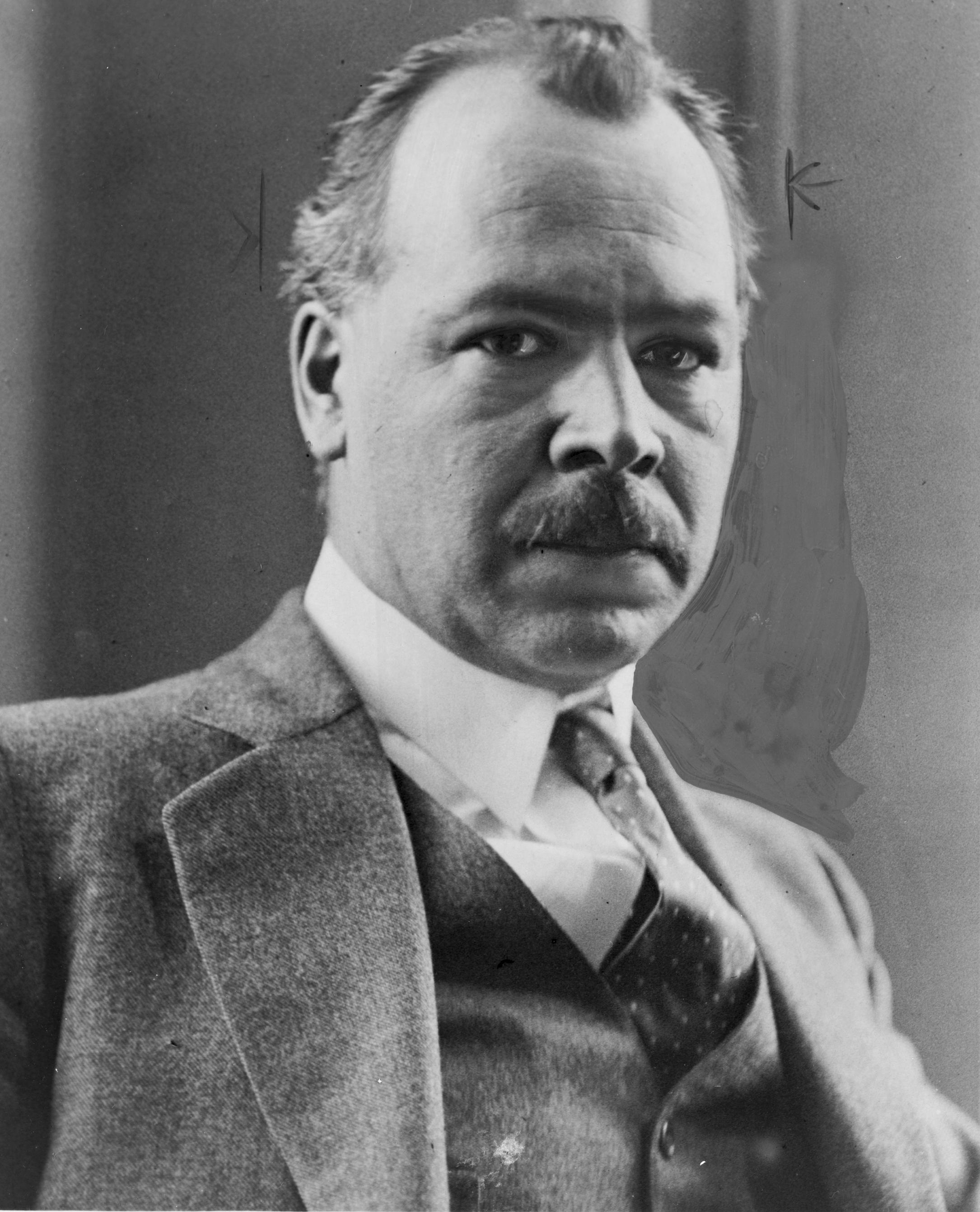

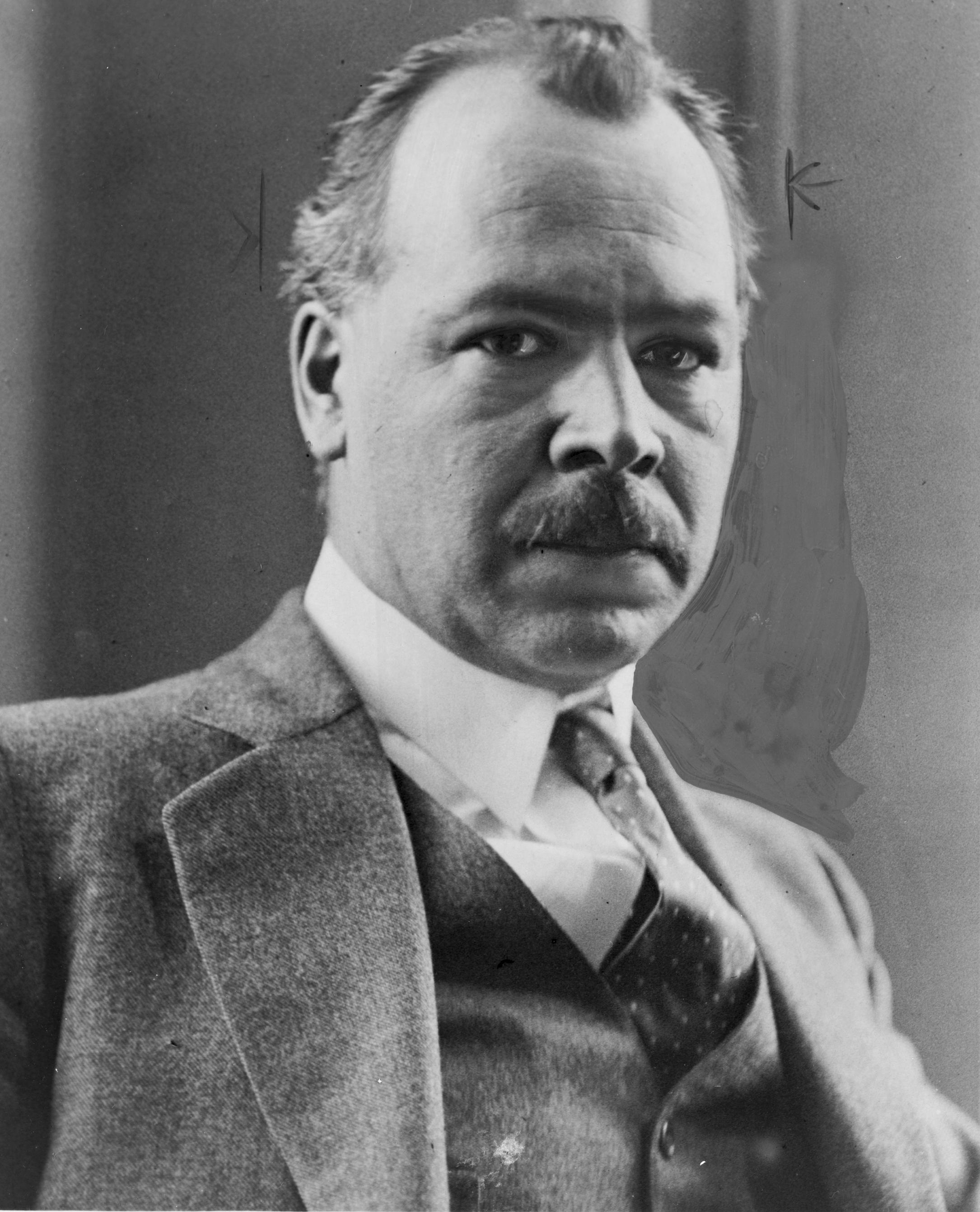

NI Vavilov (1887 - 1943)

Science &

Politics in the Soviet Union: The Fate of Genetics, 1930 -

1964

Following the collapse of the Russian Empire

and the ensuing Civil War, agriculture in the Soviet Union of the

1920s remained in a state of massive crisis, during the forced

changeover from a small-farm, agrarian-based economy towards an

industrial economy based on collective farms. Whole-sale

elimination of the Kulak peasant class, and bureaucratic

mismanagement, led to widespread famines that provoked the Soviet

government to search for any possible solution to the critical

lack of food.

Trofim Denisovich Lysenko (1898 – 1976)

was a Russian peasant agriculturist, who achieved notoriety in the

late 1920s by his advocacy of vernalization. Seeds from

winter-adapted strains of wheat, when exposed to freezing

temperatures prior to planting, were able to germinate when

planted in the spring. The method was well-known, but scientific

data had shown that it produced only marginal increases in yield.

Lysenko, instead of performing controlled experiments, made

extravagant claims that vernalization increased wheat yields by as

much as 15%, and also that the modified growth was inherited

between generations. Soviet propaganda favored inspirational

stories of peasants who, through their native ability and

intelligence, came up with solutions to practical problems.

Lysenko was widely presented as such a genius, who had developed a

new, revolutionary technique. Lysenko also associated himself with the ideas of Michurin,

another peasant horticulturist. Michurin advocated Lamarckism,

and claimed to have effected permanent changes in plant species

through hybridization, grafting, and other non-genetic

techniques. [Michurin’s methods have parallels in the work of

the American plant breeder Luther Burbank]. The notion

that acquired characteristics could be transmitted to an

organism's descendants was seen as consistent with the social

theories of Marx and Engels, who argued that nature and human

society were infinitely plastic. Lysenko's methods were

also seen as a way to engage peasants directly in an "agricultural

revolution," instead of opposing government 'reforms'. He went on

to advocate other dubious methods, such as cluster-planting of

trees (Soviet seedlings would 'cooperate,' rather than 'compete'

in a capitalist manner), scattering seed on stubble fields, and

argued for the possibility of inter-species transformations (the

sort of things that might be expected with contaminated seed)

Soviet geneticists at the time were

well-established among the world leaders in the field. These

included Theodosius Dobzhansky (1900 - 1975), whose

"Genetics and the Origin of Species" was a seminal

contribution to the New Evolutionary Synthesis, and Sergei

Chetverikov (1880 - 1959) whose work on population

genetics anticipated Ronald Fisher and Sewall

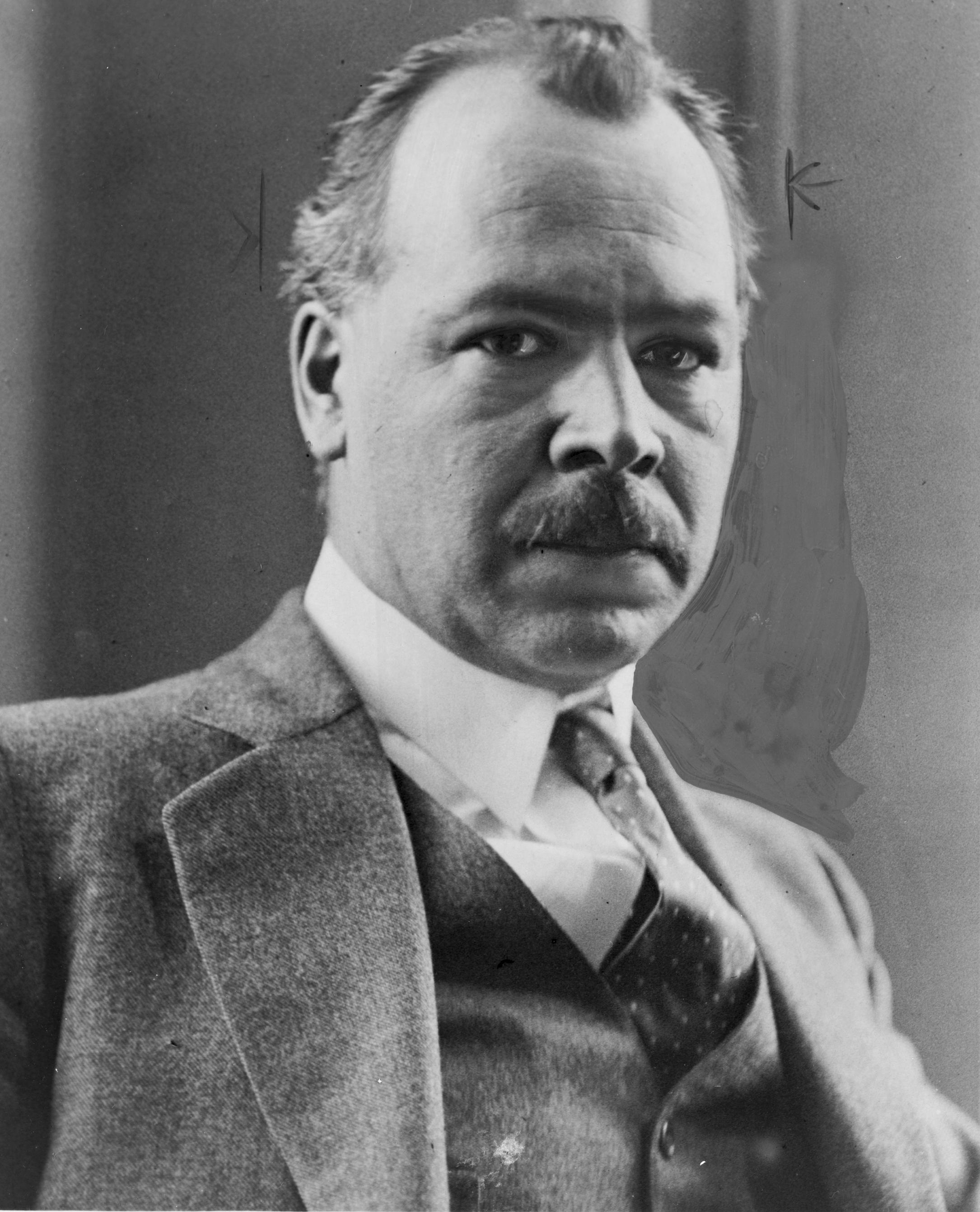

Wright. In particular, Nikolai

Ivanovich Vavilov (1887 - 1943) amassed a huge seed bank

collection for breeding. He pioneered efforts to

develop new strains of crops that were specific for the

many growing regions in the USSR, by use of controlled

crosses and heritability studies.

Left-leaning Western geneticists including future Nobelist Herman

J Muller visited Vavilov to promote East-West cooperation.

However, Vavilov's methods require several generations to show

results, academic geneticists were constrained by their

actual data and could not hope to match Lysenko's extravagant

claims. They were also no match for Lysenko's political tactics,

which presented genetics as 'western bourgeois science'.

Support from Joseph Stalin (1879 -

1953) enhanced Lysenko’s status. In 1935, during the height of the

Yezhov

Terror, Lysenko gave an address to the Politburo in

which he accused Soviet geneticists who opposed his theories of

being "Mendelist - Morganists" who set themselves against

Marxist-Leninism. Stalin was in the audience, and called out "Bravo,

Comrade Lysenko, Bravo." Lysenko thereafter began an

campaign of extreme demagoguery to slander geneticists who still

spoke out against him, and to replace the staff of genetics

research units in Soviet laboratories with his own followers. Many

of Lysenko’s scientific opponents, including Vavilov, were

imprisoned and died in the Gulag after denunciation by

Lysenko. (At the time of his arrest, Vavilov had just been elected

President of the International Congress of Genetics, but was

refused permission to travel abroad. Vavilov died of starvation in

a Gulag prison

cell.).

Following World War II, Stalin instituted a new

"anti-Cosmopolitan" campaign intended to suppress any

influence from the West, which had been tolerated during the war.

In 1948, a carefully stage-managed scientific debate between the

two schools at the Lenin Academy of Agricultural Sciences was

terminated by Lysenko's preemptive announcement that the Central

Committee had

read his position paper, and "They approved it!": Lysenkoism would

henceforth be taught as "the only correct theory". In the

subsequent scramble for survival, Soviet geneticists and

biologists were forced to denounce each other and any work that

contradicted Lysenko's theories. The anti-Cosmopolitan campaign

extended to many spheres of Soviet science and culture. Notably,

the "anti-Formalist"

campaign in music targeted the most prominent Soviet composers

including Shostakovitch, Prokofiev, and Khachaturian.

Lysenko’s domination of Soviet agriculture was

essentially complete from 1948 – 1964. Following the death of

Stalin in 1953 and eventual consolidation of power under Nikita

Khrushchev in 1958, realistic assessment of serious

shortfalls in Soviet agriculture as compared with successes

achieved by genetic means in the West came to question, and

criticism of Lysenko was again permitted. Scathing reviews of

Lysenko's results and methods contributed to Khrushchev's fall in

1964, and he was removed from all positions of authority by 1966.

Soviet biology had lost an entire generation to the political

ambitions of an ignorant demagogue.

Lysenko died in isolation in

1976. His western obituary noted, “Even the fruit flies were

killed.”