The general purpose of this paper is to underscore the need for reflective and critical internship programs in teacher education. To this end, the underlying premise of the Reflective and Critical Internship Program (Doyle, Kennedy, Ludlow, Rose & Singh, 1994) is described briefly, and each of the four main components of the internship experience (intern, cooperating teacher, university supervisor and context) is examined in light of its unique role in, and contribution to, a reflective and critical internship experience. As part of this examination, I raise a number of issues regarding the very complex relationships that exist between these individual components, and propose that this Quad Relationship (Rose, 1997) is a critical feature of a reflective internship program. In this regard, many basic issues and practices surrounding the development, administration, and evaluation of internship programs, might be clarified by first examining the fundamental nature of each of the individual components of the Quad, and then exploring the many and varied interactions that occur between them. As a starting point in this process, it is my intention in this paper to raise questions surrounding the general development and delivery of an internship program that strives to be comprehensive, meaningful and effective for all participants and stakeholders.

In putting together this paper, I have drawn upon research undertaken by a research group established in the Faculty of Education, Memorial University of Newfoundland, a number of years ago. Both as a member of this group, and as a Faculty member still actively involved in working with music education interns, cooperating teachers and supervisors, I am reminded continuously of the exciting possibilities that the internship program holds as it is identified as being the most important experience of the teacher education program (Doyle et. al, 1994).

It has been the belief of our research group that, in order for teachers to be productive and transformative in their practice, they need to have developed a critical pedagogy (Doyle, 1993; Giroux, 1989; McLaren, 1989; Weiler, 1988; Kirk, 1986; Apple, 1982b). Such a pedagogy stems from a social and cultural consciousness that encourages both self and social knowledge, political awareness, educational relevance and productivity. It is our belief such a consciousness requires reflection, analysis and critique.

One of the most important facets of teacher preparation has to do with the development of both personal and professional knowledge. This includes awareness as to how individuals, e.g., interns and their students, fit into a super-structure of educational, political, cultural and social ideals. A basic premise of our work with interns is that the development of such awareness stems from the process of reflection and continuous critical examination of the various components of education, culture and society (Rose, 1994),

We have found that an excellent opportunity to nurture the process of critical reflection in teacher preparation exists within the internship program (Doyle, Kennedy, Ludlow, Rose and Singh, 1994). The internship experience can serve as an important step toward the bridging of theory and practice, the formation of teacher identity and the development of social and cultural consciousness. It is our contention that such a step is vital to the ongoing development of a critical pedagogy.

At the heart of the internship experience is the intern. This particular experience represents a crucial and transitional time for interns in that they are juggling many pieces of a very complex whole. They are asking questions and seeking answers, testing theory, discovering rules, expectations, traditions and beliefs, developing new values and meanings, searching for roles and identity, and attempting to build a practice that is relevant and meaningful for them and their students. Given the complexity of this experience for the interns, our research group identified a need for, and ultimately felt a responsibility to develop, a context for the internship experience that not only allowed for but also nurtured the process of acquiring personal and professional knowledge and skills toward the development of a critical pedagogy. Our overall goal was to facilitate and nurture interns' personal and professional growth primarily through the enhancement of both self and social understanding. Through structured and pedagogically devised sessions involving dialogue, sharing, examining, viewing, questioning and analyzing, the interns, as well as all the other 'players' involved in the Internship Program, e.g., cooperating teachers, supervisors and administrators, were actively engaged in the process of reflection and analysis. We felt that this process provided the framework for a comprehensive 'program' for interns that was supportive and facilitative, yet challenging in nature and design. The need for such a dialectical process in the development of reflective and critical practice is pointed out by Kemmis (1985). He states, "Reflection is an action-oriented process and a dialectical process... it looks inward at our thoughts and processes and outwards at the situation in which we find ourselves... it is a social process, not a purely individual process in that ideas stem from a socially constructed world of meanings" (p. 145).

The Reflective and Critical Internship Model (RCIP)

The primary outcome of our research to date has been the development of the Reflective and Critical Internship Model (Doyle et al., 1994: 10-15). Building on the work of Smyth (1987, 1989) and others, the basic framework of this model includes five pedagogical categories, or forms of action, through which pre-service teachers travel in their construction of knowledge, skills, identities, beliefs, values and practices. Specifically, these categories provide a lens and a means through which teacher educators and students can examine the development of teacher thinking within a broad context of educational, socio-cultural and political ideals and practices.

These five pedagogical categories or forms of action are:

- Describing/contextualizing, e.g., what is the context, case, situation, orientations and realities of a particular practice? These questions include the elements of who, what, when, where, and how.

- Bringing and recognizing cultural capital (Bourdieu, 1977), e.g., what do the various partners bring to, and ultimately come to value throughout the internship program? What theories, ideologies, practices, prejudices and taken-for-granted realities are brought tot he process of teacher professionalization?

- Engaging in communication, e.g., what are the various forms of engagement involved in the internship process? How do we recognize different voices, communicate effectively with self and others, and reflect on the political and social nature of schooling?

- Problematizing dominant practices and discourses (Phelan and McLaughlin, 1992), e.g., is there a willingness and ability to ask questions, entertain doubts, be disturbed about teaching and learning worlds and the discoursed that pervade them? How do we create a process of meaning-making in which teachers infuse dominant discourses with their own purposes and intentions?

- Functioning as transformative intellectuals and cultural workers (Giroux, 1988, 1992), e.g., how might we transform our practice in a fashion that marks a real difference between being an educator and a trainer? How do we come to view pedagogy as a form of cultural production, as opposed to basic transmission of information and skills? Do we encourage interns to examine the relationships between schooling, pedagogy, cultural practices and social power? Do we strive for a language and a practice of possibility and change?

The Quad Relationship

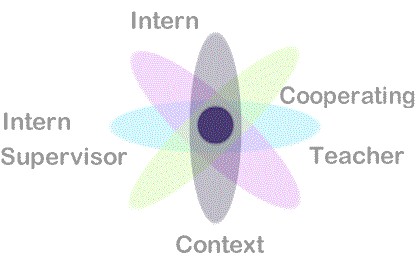

It is within the context of the RCIP Model, briefly described above, that I now discuss the underlying issues that comprise the Quad relationship in the internship program. The interconnected and interdependent relationship(s) between the intern, cooperating teacher, intern supervisor and local context are at the heart of an internship experience grounded in critical pedagogy. These four 'players' are in constant engagement and interaction. The success of the individual internship experience, in its design, development and facilitation, is very much dependent on the nature and quality of the interactions between each player in the Quad relationship. It is when the intentions and actions of these players are fused in conscious, well planned and organized ways, that the potential for a reflective and critical internship experience may be realized.

As a starting point in understanding the complexities of the

Quad relationship,

I have outlined some of the primary roles and/or issues surrounding each

player in a reflective and critical internship program. These roles/issues

stem from the needs of the RCIP Model as it may evolve into practice:

The INTERN is:

- exploring, observing, examining and critically analyzing teaching practice

- searching for, and attempting to establish, a professional role and identity

- seeking to work safely and effectively within inherited spaces and practices

- merging personal and professional philosophies and theories with practice (toward praxis)

- developing skills in fundamentals of teaching (communication, classroom management, methodologies, evaluation…)

attempting to operate 'successfully' within a very complex environment of expectations, traditions, values and beliefs (often involving conflict and contestation)

- making connections between, and developing understandings of, teaching and learning

- recognizing the influence of past experiences and knowledge on current practice

- learning to value the cultural capital of self and others

- striving for success and excellence (e.g., evaluation/recommendations).

The COOPERATING TEACHER is:

- providing a context and setting for the internship experience

- demonstrating expertise in teaching (i.e., knowledge and skill)

- facilitating hands-on teaching experiences for the intern

- nurturing the intern's development of professional practice

- providing consistent feedback and general support for the intern's developing skills and understandings

- encouraging and assisting the development of reflection-in-action (e.g., cycle of observation-reflection-action; turning awareness into action)

- encouraging the intern to incorporate own ideas and experiences into the teaching experience (e.g., experimentation, trial and error)

- raising critical questions and challenges about issues and practices inherent in the teaching/learning process (i.e., to aid in the development of critical thinkers and doers)

- assisting the intern in his/her development of understandings about the schooling process (e.g., culture of school, teacher-student relationships, connections to parents and the community, political considerations, economic realities…).

- operating as the main link to the University (Faculty of Education)

- guiding both the intern and cooperating teacher through the various process-related and administrative details of the internship program

- working with both the school and university to provide a supportive, safe and meaningful environment for the intern

- assisting the intern in his/her connecting of current teaching experiences with existing knowledge in various educational, social, cultural, political theories and paradigms

- providing safe spaces/sites for the intern, through pre- and post- conferencing and reflective group seminars, to work through and 'make sense of' issues, practices and experiences as they arise

- facilitating opportunities for quality interaction between the cooperating teacher, intern and supervisor (i.e., planning, goal-setting, ongoing evaluation, analysis…)

- nurturing and guiding the intern in his/her formation of teacher identity and professional practice

- providing consistent, appropriate and relevant feedback to the intern regarding teaching experiences throughout the semester (e.g., relating to current issues and practices of a particular subject matter and/or context)

-

engaging the intern in critical and reflective analysis (e.g., raising

critical questions and challenges about ideologies, belief systems and

practices; helping the intern to locate his/her work within both subjective

and objective frameworks).

- nature of the site (e.g., rural/urban; large/small)

- history and traditions relating to the context (e.g., values, beliefs, expectations…)

- individual and collective personalities/cultures existing within the context

- the philosophies, concepts, skills, practices, beliefs, traditions and value systems associated with the particular subject area

- the interconnectedness of subject matter with the teaching and learning process (i.e., philosophies, pedagogies, methodologies…)

- the context and setting in which the subject matter is being experienced (e.g., social studies classroom, music/mini/ multimedia/computer workstation, biology lab, choral rehearsal)

- the expertise required of all participants (intern, cooperating teacher and supervisor) in the subject matter, in order to provide the most comprehensive, relevant and meaningful internship experience

all that influences what teachers and learners do within the discipline or subject matter (e.g., constraints, perceptions, expectations, traditions… that may be peculiar to the subject matter and context).

Having identified the main components of the Quad relationship, I will now highlight briefly some guiding principles that underpin the fundamental nature of the RCIP model.

- The importance of the development of a partnership model involving the university, school districts and individual school communities. The partnership model must have as its foundation the realization of, and commitment to, the internship experience as an integral component of teacher education

- The recognition and need for establishing a partnership program that has as its basis the development of critical, reflective and intelligent practitioners. Such a program would recognize and value the internship experience as more than an apprenticeship program.

- The recognition of the intern as the central figure in the delivery of the internship program. A relevant, meaningful and pedagogically sound internship experience needs to be designed and implemented for each intern.

- The need for expertise in each 'quadrant' of the internship experience - intern, cooperating teacher, intern supervisor, and context. Expertise in this instance would be characterized for example by such elements as appropriate intern preparation and background (intern), identified excellence in teaching and subject area competence (cooperating teacher), appropriate academic preparation regarding the nature of the internship experience (intern supervisor) and, appropriate school/community placement (context).

- The need for the development of a 'system' of partnerships that recognizes and values the contribution of each participant to the success of the internship program. Such a system would require regular consultation, communication, interaction and program evaluation.

- The recognition of the important role of, and need for, ongoing research at the core of the internship experience (e.g., classroom pedagogy, the pedagogy of supervision, the nature and development of teacher thinking and practice…).

- The need for an efficient and effective administrative component in the Faculty of Education that would serve primarily to support the academic and pedagogical nature of the internship program.

- The need for ongoing professional development for cooperating teachers, intern supervisors and administrators involved with the internship program. The establishment of a standard of academic, pedagogical and administrative excellence would provide the foundation and rationale for the establishment of an agenda for professional development designed to meet the needs of a reflective and critical internship program.

-

The need for a renewed commitment to excellence in education, and particularly

to teacher preparation.

Underlying the RCIP Model and Quad relationship are some very important questions about issues such as personnel, expertise, administration and program evaluation that need to be explored and analyzed by all parties involved in the internship program. Some of the questions I pose here will serve to stimulate this process as we strive continually to refine and improve current internship programs. As we realize, some of these questions may not be new, but they do represent the complex issues surrounding the development of an internship program that is grounded in critical pedagogy.

- Who is the intern? What are his/her particular needs and interests?

- Who are the cooperating teachers?

- Who are the intern supervisors?

- How is the expertise of all 'players' identified? How, and by whom, are cooperating teachers and supervisors selected/appointed for their role in the internship program?

- Is there consistency in the delivery of the internship program between urban/rural, small/large school contexts?

- What is an appropriate system for intern placement? (e.g., how are issues relating to expertise and appropriate context accounted for in placement procedures?)

- What is the role(s) of the Faculty of Education? How might the university contribute to professional development programs, research, university-based supervision when possible and/or appropriate, and the overall administration of the internship program?How might an appropriate balance be struck between academic and administrative needs and agendas?

- What is the role of school districts as they partner with the university to provide appropriate and excellent internship experiences for interns and their supervisors.

- How should we deal with the complex issue of intern evaluation in a manner that is fair, consistent and meaningful?

- What are the needs of each partner in the internship program? For example, is the intern matched with a cooperating teacher who has identified expertise? Is supervision occurring on a regular basis? Is there a clear understanding about the pedagogy of supervision? How are workload concerns addressed for both cooperating teachers and intern supervisors?

- Are cooperating teachers and intern supervisors provided adequate time in their general workload allocations, as well as adequate resources, to meet the needs of the internship program generally, and the individual intern specifically?

- Is there a system in place that provides for ongoing professional interaction between all key players in the internship program? Is there time devoted to professional development in the form of seminars and workshops that focus on the various aspects of the internship experience?

- Is it possible to establish a formalized system within the teacher education program that addresses the issues and questions raised above? Such a system would include for example, provisions for a) the selection of cooperating teachers and supervisors, b) the formation of appropriate partnership connections involving 'official' affiliations, and designations, c) the recognition of excellence within the educational system as it relates to the internship program, d) the development of connections between the internship program, teacher certification, and general professional development plans and policies within professional teacher organizations (e.g., Newfoundland and Labrador Teachers' Association).

The internship program plays an integral part in teacher preparation. The Reflective and Critical Internship Program can provide an effective site for the nurturing of aspiring educators, as well as for the continued nurturing of many individuals who are already involved in the educational system. The overall goal of the RCIP is the creation of teacher education programs generally, and internship programs specifically, that are focussed on, and engaged in, the development of conscious, knowing, and active participants in the educational process. A critical form of this engagement involves reflection, analysis and critique. A process of engagement that is structured to encourage and facilitate such activities can be a very powerful means toward individual and collective empowerment, leading ultimately to change and transformation.

It is my hope that by exploring the RCIP Model, in conjunction with the Quad Relationship, that we will be encouraged to address, with some urgency, some of the issues and questions raised in this paper. As mentioned earlier, some of these issues are new, others have been with us for awhile. Ultimately, I hope to challenge all participants and stakeholders in teacher education to work toward the continuing development and delivery of internship programs that are characterized by intellectualism, creativity, open-mindedness, flexibility, responsibility and systematic reflection, analysis and evaluation.

Doyle, C., W. Kennedy, K. Ludlow, A. Rose & A. Singh (1994). Toward building a reflective and critical internship program (The RCIP model): Theory and practice. St. John's, NF: Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Doyle, C. (1993). Raising curtains on education: Drama as a site for critical pedagogy. New York: Bergin and Garvey.

Giroux, H. (1983). Theory and resistance in education. London: Heinemann Educational Books)

Kemmis, S. (1985). Action research and the politics of reflection. In D. Boud, R. Keough and D. Walker (Eds.). Reflection: Turning experience into learning. London: Kogan Page.

Kirk, D. (1986). Beyond the limits of theoretical discourse in teacher education: Towards a critical pedagogy. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2(2), 1555-167.

Smyth, J. (1987) (Ed.). Educating teachers - Changing the nature of pedagogical knowledge. London: Falmer Press.

Smyth, J. (1989). A critical pedagogy of classroom practice. Curriculum Studies. 21(6), 483-502.

Weiler, K. (1988). Women teaching for change. New York: Bergin and Garvey.