|

The purpose of

this paper is to investigate the basis of Newfoundland humor from an

historical and cultural perspective to assess whether a claim to uniqueness is

justifiable, and, as well, to evaluate the impact of recent socio-political

movements on the future of Newfoundland

humor. All provinces and all peoples claim to possess some regional,

cultural or ethnic diversity as an important part of their identity

definition. In the 1980s and 1990s there was an increase in Canadian

regionalism, reflected in the strength of two new regional political parties

and the failures of two proposed constitutional accords to compromise

centralizing and de-centralizing tendencies. All provinces see

themselves as unique, and they may be, but one may be just a little more

so? It is the belief of Herbert Lench Pottle that:” ...the

peculiarities of the Newfoundland

character today have a logical, meaningful and indeed inevitable linkage with

all of Newfoundland’s

yesterdays” (Pottle, 1983: 10).

Though Newfoundland

was the first province visited by Europeans, it was the last permanently

settled and the last to enter Canada

in 1949. This province was always viewed as a colonial possession first

by the French, then by the British and now by the Canadians (this

relationship is certainly under question with the failure of the fish

stocks). “All the while our cousins on the continental mainland

were organizing themselves into communities, raising their families, choosing

their governments, we Newfoundlanders were battling for the primitive right

to settle at all – outlaws in fact on alien soil” (Pottle,

1954:11). From the very beginning, survival in Newfoundland

was a struggle: a struggle against temporality; a struggle against the

fishing admirals who came to exploit; a struggle against each other, in the

absence of law and order and during the winter months, and a struggle to find

food and firewood to maintain life. This unique and austere environment

became the setting for the evolution of Newfoundland humor.

Cyril Poole as well locates much of the Newfoundland character in an

adaptive response to the precarious weather: “Because we have not

been able linguistically to slay our enemies, fog and rain, sleet and snow,

we must each day go forth and do battle with them. And the battle has

moulded our character” (Poole, 1982: 43). For Richard Gwyn the Newfoundland character was

“forged ... out of hereditary and environment. Newfoundlanders are

proud and sentimental, tough and impractical.” They are a people

who “rejected the dynamism and tyranny of the Protestant ethic for a

humanism which placed people above things and the spiritual above the

material” (Gwyn, 1970: 62). James Overton as well feels that:

“It is a culture that has developed organically in isolation and it is

the environment (especially the sea) that has been one of the key forces

which has moulded the Newfoundland

character” (Overton, 1988: 11).

In

1994, on C.B.C’s Cross Country Check-up, Rex Murphy was in conversation

with an Editor of “The Globe and Mail,” when the latter

stated: “There is no doubt that Newfoundland has a distinct

culture.” Later in the same program a Mr. Parsons phoned in from Nova Scotia

to comment that ... “he left the fishery for education. He would

like to return. The issue is not just economic. There is a

cultural uniqueness here (Nfld)” (C.B.C., March 13, 1994).

The difference between Newfoundland

and the other Atlantic Provinces

also appears to be the basis of methodological decisions when conducting

Sociological Research: “...researchers sometimes divide Newfoundland from the

rest of Atlantic Canada...”

(Baer, Grabb and Johnston, 1993: 16).

Newfoundland is the

only province where the majority of the residents live on an island in the

middle of the Atlantic and combined with the

Labrador Peninsula are the eastern most

points in Canada.

Demographically, the province is the most religiously homogeneous (with the

exception of Quebec),

it has the lowest rate of persons speaking the two official languages, and

has the highest rate of births in Canada within its own province

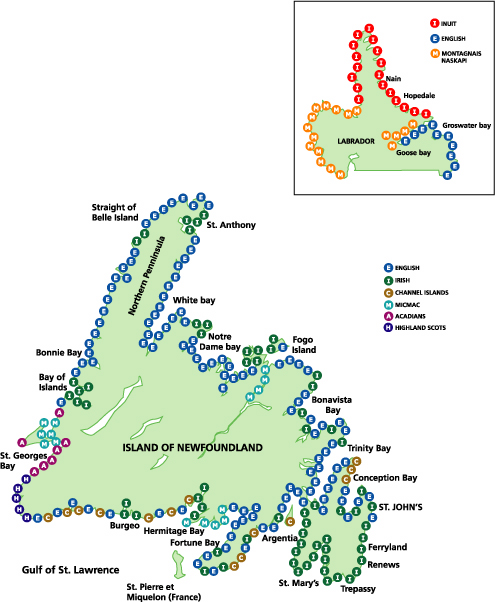

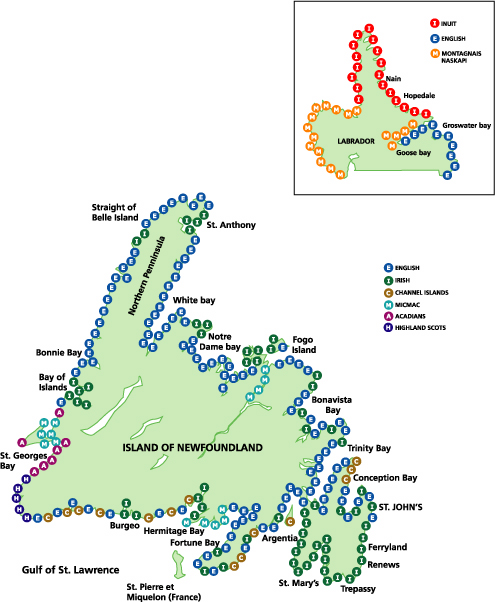

(Hillier, 1991: 23, 22, and 27). The vast majority of the population

can

trace an ancestry to either the south of England or Ireland with

a smaller number of immigrants coming from Scotland (Mathews, Kearley, Dwyer

1982: 65) (see appendix 1). The uniqueness of the culture and its

strong ties with the past can be appreciated when one realizes that the

province has produced two editions of The Dictionary of Newfoundland

English. The first edition contains 624 pages of unique Newfoundland

expressions while the second edition adds to the first and presents 770 pages

of unique expressions (Story, Kirwin and Widdowson 1982, 1990). The

physical location, the uniform roots, the unique preservation of historical

language were all melded by the continuous austerity of the environment and

provided the setting for the evolution of Newfoundland humor:

The stage was bountifully

set where they could laugh with relish at themselves and with resonance at

one another.

The natural habitats of

these manifold forms of humor were such hives as one another’s homes,

merchant’s stores, stage heads, the squid - jigging ground, at

‘times’ (local suppers and sales), launching and hauling up

boats, mummering, lodges, lumber camps... It is not much of an

exaggeration to say that where two or three are gathered together, they are

likely as not to be swapping yarns. (Pottle 1983:13)

As Newfoundland and Labrador humor appears to have evolved from the

precarious conditions of the lives of the people, it would be considered

functional for survival. The removal of this adaptive mechanism posing

a threat to the stability of the people. The relationship between humor

and the conditions of ones existence is not peculiar to the people of Newfoundland and Labrador. Lawrence W. Levine reviews the book On

the Real Side and states:

“Humor allows us to

discuss virtually everything, no matter how taboo. Subjects like incest,

sexual performance, prejudice, class feeling, even intense anger toward those

on whom we are emotionally or materially dependent, can be expressed openly and

freely once they become part of humorous expression. This is

undoubtedly why many of those who have experienced the most consistent

oppression – blacks, Jews, and Irish – have such a

highly developed sense of humor. (Levine, New York Times, February 27, 1994:

3)

Though the cause of the oppression of the Newfoundlander and Labradorian can

be linked to the environment and economic uncertainty rather than the social

structure, the effect on the evolution of the humor is very similar.

This fact would be supported by the French philosopher Montesquieu (1689 -

1755) who Cyril Poole (1982) finds a source of inspiration:

“...the strength of

passions and the clarity of thought are largely determined by climate. . . .

cold air ‘constringes the extremities of the fibres’, while

’warm air relaxes and lengthens the extremities of the external fibres

of the body’....in cold climates people are more courageous, bolder,

less suspicious, less cunning, and more open and frank. ...our (Newfoundlanders)

spirits are set in motion only by such strong stimuli as ‘hunting,

travelling, war and wine.’ .... ‘the bravery of those in cold

climates has enabled them to maintain their liberties.’”

(Poole, 1982: 48-49)

Herbert Pottle reinforces this point when he acclaims:

“Traditionally, in the light of the adverse weather conditions of Newfoundland history,

humour has been both an individual and a collective means of enabling life to

be tolerable” (Pottle, 1982:14).

Though the second major source of humor (economic uncertainty) has improved,

relative to the province’s extremely humble beginnings, the source of

this humor has shifted from the local merchant to the political patronage of

governments:

This rather sudden

somersault of condition - the turnover of traditional initiative to political

handout – has not been lost on Newfoundland humor, compounded mostly of

satire, which has been enjoying a roaring trade, the politicians being both

suppliers and customers. (Pottle, 1982:15)

Though Pottle made this comment over two decades ago, its current validity is

still without question as we reflect on the recent successes of two of Newfoundland’s

comedy troupes. “This hour has 22 Minutes” was awarded The

Golden Gate Award for 1993 in San Francisco

which received participation from over 1200 entries from 51 countries.

This was the largest film festival in the world and their award was in the

Comedy Category. Also, “Codco” was awarded two Geminis awards for

1993: Best Writing of a Variety Program or Series and Best Performance

in a Comedy (C.B.C. Files, St.

John’s, NF).

Both groups tend to emphasize political or cultural incongruities or

combinations of both. These are only two of the more prominent comedy groups;

there are many others: Buddy Waissisname and the other fellows, Rex

Murphy, Ray Guy, Snook, Al Cluston, Joe Mullins, Ross Goldsworthy, and Mixed

Nuts – all performing throughout the province on different

occasions.

The

evolution of the humor on this tiny province can be attributed to a number of

factors, already mentioned; but another significant influence is the absence

of any significant censorship. As soon as a story hits the news, local

comedians are guaranteed to be spreading wit, usually by word of mouth, within

a matter of maybe hours and certainly days. Child abuse; homosexuality

discovered in public washrooms; the Bobbits; Waco, Texas

Immigration Irregularities; and anything else can be the subject of fresh

humor. This is usually prompted by: “Got either fresh

one?” or “Any new ones on the go?” or “I

haven’t heard a story in ages?” The latter is a reminder of

the oral tradition which was once dominant in the culture and is still

present. No subject is too sacred or according to Herbert Pottle:

“There seems to be no area of life too intimate for the advances of

repressed humor.” Pottle illustrates this point by recounting the

traditional story about the baby born with no ears and nobody wanted to

mention this point to the parents for fear of offending them until Levi (the

grandfather of the child) came to visit. Levi avoided all mention of

the babies ears but continued to comment on the child’s very fine eye

sight. At one point the mother said, “Why are you asking about

his eyes?”

“Well,” sputtered Levi, “his eyesight better be good

because, poor little crater, he’ll never be able to wear

glasses.” (Pottle, 1982:28)

The

reader might appreciate a ‘fresh one’: Clyde Wells had an

accident the other day; he was out for a walk and was hit by a fishing boat

(late night party, Churchill Falls, April 21, 1994, 2 a.m.).

There is no topic too sacred to be ridiculed through humor; however, some may

argue that they have lived on the island for a number of years and have not

experienced uncensored humor. If this be a retort, the speaker has

removed himself/herself from the inner catacombs of the humor tunnels.

Much of Newfoundland’s raw humor is potentially offensive, and if an

individual were to show the slightest signs of offense or dismay at a mild

linguistic nuance then they are removed from the list of those who would

other wise be entertained. The day-to-day interactions which form the

context for the advance of the wit are not intended to offend and hence, an

individual who responds adversely is immediately denied access:

It is quite safe to say

that when Newfoundlanders get into a huddle, a humorous story is much more

likely than not what brings them together and keeps them so... Their

common ground is so firm and so redoubtable that anyone who cannot share the

same premises feels like an outsider. (Pottle, 1982: 30)

Much of Newfoundland’s

humor is pointed at Newfoundlanders themselves, but they are also prepared to

turn a phrase at the expense of minorities, women, men, children, dogs, cats,

clergymen, businessmen and sometimes even politicians. But the teller

does not believe, nor wishes to convey, some deep social commentary and

certainly does not wish to be accused of some anti-democratic intention which

did not exist: “Unlike the poisoned barb of satire and the

killing poiny of wit, humor is healing. It is not only wholesome, but

recreative and rejuvenating” (Shalit, l987: 2). The Newfoundlander

does not believe that the Newfoundlander is stupid, blacks are inferior, Jews

are cheap, women are unequal to men or that all politicians are

dishonest. But they are aware of the existence of these stereotypes and

this notion becomes one of the bases of the humor. Always, the joke remains a

joke, whose raison d’etre is pure entertainment void of a significant

social commentary.

Robert Stebbins identifies four types of humor. These are consensus,

control, conflict, and comic relief (Stebbins, 1990: 47-49). The humor

of the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador should be classified as

consensus humor creating feelings of friendliness and good cheer, and comic

relief or release from a tense situation (See Pottle, above). Control

humor, intended to annoy; and conflict humor, an act of aggression have no

place within context of Newfoundland

wit.

This point is shared by Martin and Baksh who conducted an extensive empirical

study of Atlantic Canadian School Humor. They referred to Damico

(1980:133) who discovered through her sociometric study of adolescent class

clowns that they can release tensions within the classroom and increase a

sense of group cohesion among the students (Martin and Baksh

1995:14). They also referred to Hill (1988:20-24) who listed eight

functions of humor. Her sixth she classifies as “appeasement

function of humor” which makes light of an otherwise serious issue and

the seventh is a “coping mechanism” through which students share

their personal problems (Martin and Baksh 1995:19). Both of these

functions are related to the way humor is used in the province of Newfoundland

and Labrador.

It

is difficult to separate humor and culture. Woods (1983:114)

found that students used humor to test the water in developing their own

culture. Woods also found that joking forms a cultural bond between

teacher and student (Martin and Baksh 1995:24,21). In school and out of

school it appears as though sharing one’s sense of humor is sharing

one’s culture.

The

function and nature of Newfoundland

humor is not always clearly understood by those who are not completely

immersed in the culture of the province. There are occasional attacks

against which the province must fortify itself. These attacks come from

individuals who have never lived in Newfoundland and Labrador and encounter

the culture for the first time, or from individuals who did live in the

province and have lived ‘up along’ (1) for many years and feel

they must protect the province from the perceived dangers of traditional

stereotypes. The format which the latter expression approximates is a

hybrid combination of Newfoundland

roots with upper Canadian self-consciousness.

On November 10, 1993, a sports

reporter for the Gander Beacon presented an editorial which heavily

criticized a local entertainer. The comedian was speaking at the annual

Fireman’s Ball and the female reporter, originally from Nova Scotia, had only

spent a short time in Gander,

Newfoundland. She called

Mr. Ross Goldsworthy a racist and extremely irresponsible. Her article

was entitled: “appalled, dismayed and disgusted.” The

very next week the paper was inundated with letters to the editor in defense

of Mr. Goldsworthy, he received 30 to 40 phone calls at home and hundreds of

supporting comments on the streets of Gander.

There was not one note of support for the journalist, Angela MacIsaac.

A typical letter written in support of Mr. Goldsworthy was presented by Janet

Samson who said: “I know the jokes that were told and I know that

these jokes were made to poke fun at the naivety of Newfoundlanders.

After all, if we can’t laugh at ourselves, who can we laugh at.

Ms. MacIsaac if you didn’t get the joke, you should have asked for an

explanation before printing your so called commentary” (Gander Beacon,

November 10 and 17, 1993).

In

April, 1993, Mr. Harry Brown, a retired C.B.C. broadcaster, originally from Newfoundland, spoke on

C.B.C. television against “Snook” (Peter Soucy), a popular

commentator on the C.B.C. who performs in the guise of street local from St. John’s.

Mr. Browne said: “He perpetuates the stereotype. He tries

to spend five minutes of my time telling me how stupid I am. And

convincing any potential investors that his original assessment of Newfoundland was

correct. If he were black or female, he would be fired” (C.B.C.,

Here and Now, April, 1993).

On April 8, 1993, Rex Murphy

a commentator for C.B.C responded to Harry Browne’s remarks and

provided a caustic attack on Mr. Brown and full support for

“Snook”. “Snook” himself responded and reminded Mr.

Brown of the many comedians this province has produced in the past; in

“Snook’s” words: “come on Harry bye, lighten

up!” There were no commentaries in support of Mr. Brown (C.B.C.,

Here and Now, April, 1993).

Later in April, a Toronto

woman, Lillian Elaine, originally from Newfoundland,

aired her disgust with a Toronto

newspaper which ran an ad for a computer course to be taught in many

languages – one of which was Newfie. She felt it made her

embarrassed as there was no such language as Newfie. This prompted

C.B.C. to ask people on the streets of Newfoundland

what they thought of the term Newfie and the comments of Ms. Elaine. Of

the 27 people interviewed, four were against the term, 20 found no fault with

the term (many felt honored by the term) and three were against the term

because they preferred to be called Labradorians (C.B.C., Here and Now,

April, 1993).

These situations reflect the current clashes which are beginning to surface

as the definition of reality, historically enjoyed by Newfoundlanders, begins

to collide with the dominant definition of reality which is prevalent

throughout much of Canada.

These incidents reflect to a degree the Politically Correct definition of

acceptability, dominant in some circles of the non-Newfoundland Canadian

culture and its apparent antithesis which is more prevalent in Newfoundland.

According to Maclean’s . . .“a new, rapidly unfolding moral

order, it is considered unacceptable for a white person to be critical of

minority groups.... seemingly disparaging references to color, sex or sexual

preference be banned” (Maclean’s, May 27, 1991:40). Much of

the humor of the Province

of Newfoundland and Labrador, contains references to sex, sexual practises

and sometimes to racial groups; however, the brunt of most jokes is the

Newfoundlander. Is this acceptable? Especially when

“Ethnographic research is based on the premise that what becomes

defined as humor is subjective” (Martin and Baksh 1995:38).

At

the University of Pennsylvania, Dr. Murray Dolfman, a successful lawyer and

popular part time lecturer, was suspended for asking an Afro-American to read

twice a section from the 13th Amendment dealing with enslavement; the

students and administration felt the student was being singled out.

At

Harvard, a bitter controversy developed over the desires of gays and lesbians

to express their sexuality, and the rights of heterosexuals to express their

attitudes toward homosexuality.

At Stanford University, Rudy Fuentes, co-founder

of MeCha, a student multicultural organization, was intimidated, threatened

and encircled. He was called Politically Incorrect for not supporting

the faction of the organization which wished to become more militant over

multiculturalism.

At Penn State

University, Nancy

Stumhofer, fought to have a reputable painting of a naked woman removed from

the music room she was required to use. Her claim was that the painting

constituted harassment. The administration complied.

At

the University

of Washington, Seattle, body builder

Peter Schaub found himself in a bitter controversy when he decided to enrol

in Women’s Studies 200. He contradicted the instructors who he

found were promoting lesbianism and male hatred while teaching women how to

be sexually independent. At one point in the course, the belief that

families would better without males, was advanced. The dean promised to

give him credit for the course without completing the required assignments as

long as he removed himself from the class (Pack, ”Campus Culture

Wars”, 1993).

Professor Graydon Snyder, a 63 year old tenured professor at the Chicago

Theologian Seminary, has filed a lawsuit against his school’s

disciplinary board. He was placed on probation and required to undergo

psychological therapy for making a reference to the Talmud, the Jewish Book

of Laws, where it states that a man is not liable to ‘indemnify her for

indignity unless it was intentionally caused.’ In the theoretical

scenario, a man fell from a roof and accidentally inserted his penis (Globe

and Mail, March 1994).

These American incidents do not relate directly to the context of Newfoundland’s

outlandish humor. The two have never met on the same playing

field. Many Canadian academics feel that this movement has strongly

penetrated Canada,

with the zero tolerance movement sweeping Ontario (C.B.C., Morning Side, February 3,

1994). Harry Browne, Lillian Elaine, and Angela Maclssac may be

examples of others yet to come. James Overton states:

The assumption of a common

culture and character and the argument that this needs to be defended against

outside destructive forces has a number of political implications. The

search for and the embrace of Newfoundland culture in many places goes hand

in hand with a rejection of all that is held to be alien to the Newfoundland

essence.... it is this character that makes it difficult for Canadians

to accept politicians such as John Crosbie and Brian Peckford.... an

expression of the Newfoundland soul that is just a little too ethnic for

central Canadians to accept. (Overton, 1988: 14-15)

While the ”Zero tolerance” movement in Ontario has recently been satirized in

Saturday Night magazine, the reader is sometimes left to ponder on the degree

of exaggeration used for satirical purposes. Though fulfilling an

important criteria for good humor – reflection creates

apprehension (Frazer, ”Saturday Night”, April, 1994: 10 and 74).

While many fear that the Politically Correct movement may be a new form of

McCarthyism (MacLean’s, 1991: 45) or puritanism (MacLean’s, 1991:

41), it becomes obvious that society cannot exist for too long without some

form of control. The Temperance Society was established to protect

society from hedonistic, demonic urges. Piloted primarily by responsible

ladies, it attempted to guarantee that society would reach the highest ideals

of religious fundamentalism. With the secularization of religion and

the subsequent erosion of the Temperance Society, the Politically Correct

movement provides society with a new means of control. Piloted by young

academics, this new movement aspires to create a society which fulfils the

highest ideals of democracy. Perhaps, the new movement will have as

much effect on Newfoundland

and Labrador as its predecessor:

As a result of dedicated

temperance work, imports dropped from 277,808 gallons of liquor in 1838 to

94,268 in 1847; nine years later the total was up to 256,361 gallons.

In 1858 the Total Abstinence and Benefit Society was founded; and in 1883 the

Newfoundland Brewing Company. The Temperance League was rushed into the

breach in 1872; twenty years later the number of saloons in St. John’s had increased to

fifty-eight. (Poole, 1982: 16)

At

this juncture in history it appears as though the Politically Correct (PC)

movement may have had as much effect on Newfoundland and Labrador

as the prior restrictive order. However, academics are worried that

this new movement may create intellectual rigidity as it seems to be based

more on harassment and intimidation, rather than open debate

(MacLean’s, 1991: 45). One of the assumptions of this new

movement is that humor is a reflection of a particular attitude on the part

of the teller and the telling transfers this attitude to others. There

is no room for an alternative possibility – that humor may have a

life of its own void of any significant social commentary. While the PC

movement may be attempting to protect minorities from oppression, it may be

evolving toward its own self-contradiction by imposing a preordained

definition of reality on a new context. Deluze and Foucault both feel

“the intellectual is no longer commissioned to play the role of advisor

to the masses and critic of ideological content, but rather to become one

capable of providing instruments of analysis... Jean-Francois Lyotard takes

this position even a step further by adamantly declaring the death of those

intellectuals whose aim it is to speak on behalf of humanity in the name of

an abstract and moralistic truth... For Lyotard, there is no universal

subject capable of putting forth a new concept of the world” (Kritzman,

1988: xii). “Discourses dominant in a historical period and

geographical location determine what counts as true, important, or relevant,

what gets spoken and what remains unsaid” (Cherryholmes, 1988:

35). Here Foucault is reminding us that context remains the basis of

truth and acceptability.

Barry Adam recently analyzed new social movements and found that much of the

analysis of new social movements suffers from either too much or too little

attention given to a Marxian perspective. It becomes difficult to

conceptualize Newfoundland

humor as some new anti-state response to economic imperialism. The

Newfoundland culture is only new to those who have yet to encounter it, but

what it does share with other ‘new movements’ is “the right

to be ourselves without being crushed by the apparatuses of power, violence,

and propaganda” (Adam, 1993: 324). Adam sees ‘how people

come to identify themselves’ as basic to new social movements.

In

recent years, Newfoundlanders have become conscious of the fact that they

have a different culture which must be preserved. Many Newfoundlanders

are beginning to question the impact which Confederation may have had on the

Newfoundland culture (C.B.C., Here and Now, April 7, 1994): “Academics

have begun to write copiously about the Newfoundland soul and character and

about cultural revival, and there has been the development of what F.L.

Jackson terms ”‘Newfcult in the arts’”

(Overton, 1988: 6).

Throughout this report there has been an assumption that the humor of the

province is completely uniform; however, given the geographic isolation of

costal regions – variety exists. The writer of this

report has found one particular joke which he has told over 100 times and

discovered that all people from Newfoundland

and Labrador laughed; however, only one

third of non-natives enjoyed this joke. (Note: There is no

attempt at legitimate scientific connections in these assumptions). The

joke is about a Newfoundlander from the island portion who was in a field

with a bunch of sheep. He would grab a sheep, put it up to an apple

tree, give the sheep a bite and put it down. He was doing this with all

the sheep when a mainlander (a person who is not a native of the province)

came by and said, ”Sir, it’s none of my business, but you’d

save a lot of time if you climbed the tree, shook it and let the apples fall

and then the sheep could eat whenever they wanted.” The

Newfoundlander pondered for a few seconds and replied: “Bye,

what’s time to a sheep.” One of the important aspects of

this culture is the all-pervasive and spontaneous humor, as Peter Newman

recently states:

Great art, really great

art, whatever its format, must be guided by an invisible hand: the

spontaneous blossoming of humanity caught in a moment’s creative

impulse. That’s even more true of great people, like

Newfoundlanders. Spontaneity is their middle name.”

(Newman, Maclean’s, 1994: 45)

The

PC movement stands as the antithesis of spontaneity and hence of Newfoundland

culture. Allan Dershowitz comment on the effect this movement will have

on the academic community: “We will see far worse teaching as

teachers will have to think about every term, every illustration”

(Pack, Campus Culture Wars, 1993). The possibility of offence will

serve as an inhibiting force in even face-to-face interactions and pose a

threat to the spontaneity of the people and a threat to the culture.

The

Newfoundland

culture evolved from the precarious circumstances of the lives of the

people. The element of humor was functional for their adaptation in the

face of physical and economic uncertainty. It is a humor which is

intended to provide consensus and relief but not control and conflict

(Stebbins). As Newman states: “To be a Newfie is to be a

survivor. That great spirit is in jeopardy. They are about to

become an endangered species” (Newman, MacLean’s, 1994:

45). While Newman is primarily referring to the devastating impact that

the failure of the fishery is having and will have on the culture of the

island, the essential assumption is identical. One threat is economic

– the other ideological. The construction of knowledge is derived

from experience itself. As Foucault said: “How can the

subject tell the truth about itself?” (Kritzman, 1988: 38).

How can a Newfoundland

academic whose avocation is stand-up comedy accurately analyze the

relationship between Newfoundland

culture and the Politically Correct movement? How does someone who has

never lived in Newfoundland

interpret it? Economics and ideology must work for the preservation of

this culture!

(1) The value of any

culture ultimately depends not on good books or great art, but on the passage

of people’s seed from one generation to the next, on their link to the

soil and the sea. The Newfoundlanders’ life force is expressed

less in words than in deeds – in the compassion and humor they feel for

one another when there is nothing else available to share. That’s

what is really at stake in Newfoundland

these days. And that’s why Canadians who don’t live on the

Rock should not begrudge the relatively modest tax burden to keep our most

vibrant culture alive and kicking. (Newman, MacLean’s, 1994: 45).

The expression used for Canadians who are not from Newfoundland. They live physically

up and along from Newfoundland.

References

Adam, Barry D. 1993. ‘Post –

Marxism and the new social movements,’ Canadian Review of Sociology

and Anthropology, 30(3): 316-336.

Baer, Brabb and Johnson 1993. ‘National character, regional

culture and the values of Canadians and Americans,’ Canadian Review

of Sociology and Anthropology, 30(1): 16.

Canadian

Broadcasting Corporation

1993 “Here

and Now”, April 1, St.

John’s, NL.

1993 “Here

and Now”, April 8, St.

John’s, NL.

1993 “Here

and Now”, April 12, St.

John’s, NL.

1993 “Here

and Now”, April 15-27, St. John’s, NL.

1994

“Morning Side”, February 3, 1994.

1994

“Cross Country Check-up”, Montreal,

March 13, 1994.

1994

“Here and Now”, April 7, St. John’s, NL.

CherryHolmes, Cleo H. 1988. Power and

Criticism. New York:

Teachers College Press.

Damico, Sandra

Bowman 1980. “What’s

Funny About a Crisis? Clowns in the Classroom.” Contemporary

Education, Vol. 51, No. 3 (Spring).

Fennel Torn 1991. ‘The

Silencers’ McLean’s, May 27:

40-43.

Gander Beacon 1993. ‘Appalled,

Dismayed and Disgusted’, November 10, Gander, NL. 1998 ‘Letters to the Editor,’ November

17, Gander,

NL.

Globe and Mail 1994. ‘Theologian

sues over harassment complaint,’ March.

Gwyn, Richard 1970. Smallwood:

The Unlikely Revolutionary. Toronto:

McClelland and Stewart.

Hill, Debora J. 1988. Humor in the Classroom: A Handbook

for Teachers (and Other Entertainers). Springfield, Illinois:

Charles C. Thomas.

Hillier, Harry H. 1991. Canadian

Society, A Macro Analysis. Scarborough:

Prentice-Hall.

Kritzman, Lawrence D. (ed.) 1988. Politics,

Philosophy, Culture. New

York: Routledge.

Levine, Lawrence 1994. ‘Laughing

Matters’ New York Times Book Review.

Matthews, Kearley and Dwyer (eds.) 1982. Our Newfoundland and Labrador Cultural Heritage/Part One,

Scarborough, Ontario: Prentice-Hall.

Newman, Peter C. 1994. ‘To

kill a people – dash their dream’, McLean’s, April

25: 45.

Overton, James

1988. ‘A Newfoundland

Culture?’ Journal of Canadian Studies, 23: (1 and 2).

Pack, Michael

1993. ‘Campus Culture

Wars’, Manifold Productions, (with South Carolina E.T.V.).

Poole, Cyril 1982. In

Search of the Newfoundland

Soul. St. John’s:

Harry Cuff Publications.

Pottle, Herbert Lench 1983. Fun on the Rock,

Toward a Theory of Newfoundland

Humor. St. John’s:

Breakwater Books.

Shalit, Gene (ed.) 1987. Laughing Matters. New York: Ballantine Books.

Stebbins, Robert

A. 1990. The

Laugh Makers. Montreal:

McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Story, Kirwin and Widdowson (eds.) 1990. Dictionary of

Newfoundland

English. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Other Related References

Ermarth, Elizabeth

Deeds 1992. Sequel to

History, Postmodernism and the Crisis of Representational Time. New Jersey: Princeton.

Forgacs, David (ed.) 1985. Antonio

Gramsci, Selections from Cultural Writings.

Cambridge: Harvard University

Press.

Foucault, Michel

1972. The Archaeology of Knowledge. New York: Pantheon Books.

Martin and Baksh 1995. School Humor: Pedagogical and

Sociological Considerations, Memorial

University of Newfoundland.

Massumi, Brian 1992. A User’s guide to Capitalism

and Schizophrenia. Cambridge:

Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

McCormack, Thelma

1992 “Politically Correct”, Sociology and Anthropology

Bulletin. May.

Ryan D. and Rossiter T. (eds.) 1983 Literary Modes

(See Comic Mode) St. John’s:

Jesperson. 1984 The Newfoundland Character. St. John’s:

Jesperson Press.

Woods, Peter

1983 “Coping at School Through

Humor.” British Journal of Sociology of Education, Vol.

4, No. 2.

|